Qualitative Text Analysis: A Systematic Approach

- Open Access

- First Online: 27 April 2019

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Udo Kuckartz 4

Part of the book series: ICME-13 Monographs ((ICME13Mo))

128k Accesses

241 Citations

3 Altmetric

Thematic analysis, often called Qualitative Content Analysis (QCA) in Europe, is one of the most commonly used methods for analyzing qualitative data. This paper presents the basics of this systematic method of qualitative data analysis, highlights its key characteristics, and describes a typical workflow. The aim is to present the main characteristics and to give a simple example of the process so that readers can assess whether this method might be useful for their own research. Special attention is paid to the formation of categories, since all scholars agree that categories are at the heart of the method.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Background and Procedures

Mixed Methods

Qualitative Methodology

- Qualitative data analysis

- Text analysis

- Qualitative methods

- Qualitative content analysis

- MAXQDA software

8.1 Introduction: Qualitative and Quantitative Data

Thematic analysis, often called Qualitative Content Analysis (QCA) in Europe, is one of the most commonly used methods for analyzing qualitative data (Guest et al. 2012 ; Kuckartz 2014 ; Mayring 2014 , 2015 ; Schreier 2012 ). This chapter presents the basics of this systematic method of qualitative data analysis, highlights its key characteristics, and describes a typical workflow.

Working with codes and categories is a proven method in qualitative research. QCA is a method that is reliable, easy to learn, transparent, and it is a method that is easily understood by other researchers. In short, it is a method that enjoys a high level of recognition and is to be highly recommended, especially in the context of dissertations.

The aim of this paper is to present the main characteristics and to give a simple example of the process so that readers can assess whether this method might be useful for their own research. Special attention is paid to the formation of categories, since all scholars agree that categories are at the heart of the method.

Let’s start with some of the basics of data analysis in empirical research: What does ‘qualitative data’ mean, and what do we mean by ‘quantitative data’? Quantitative data entail numerical information that results, for example, from the collection of data from a standardized interview. In a quantitative data matrix, each row corresponds to a case, namely, an interview with a respondent. The columns of the matrix are formed by the variables. Table 8.1 therefore shows the data of four cases, here the respondents 1–4. Six variables were collected for these individuals, on a scale of 1–6, concerning how often they perform certain household activities (laundry, small repairs etc.). Typically, these kinds of data sets are available in social research in the form of a rectangular matrix, for instance as shown in Table 8.1 .

A matrix like this that consists of numbers can be analyzed using statistical methods. For example, you can calculate univariate statistics such as mean values, variance, and standard deviations. You can also generate graphical displays such as box plots or bar charts. In addition, variables can be related to each other, for example by using methods of correlation and regression statistics. Another form of analysis tests groups for differences. In the above study, for example, the questions ‘Are women more frequently engaged in laundry than men in the household?’ and ‘Are men more frequently engaged in minor repairs than women in the household?’ can be calculated using an analysis of variance.

Qualitative data are far more diverse and complex than quantitative data. These data may comprise transcripts of face-to-face interviews or focus group discussions, documents, Twitter tweets, YouTube comments, or videos of the teacher-student interactions in the classroom.

In this chapter, I restrict the presentation of the QCA method to a specific type of data, namely qualitative interviews. This collective term can be used to describe very different forms of interviews, such as guideline-assisted interviews or narrative interviews on critical life events conducted in the context of biographical research. The latter can last several hours and comprise more than 30 pages as a transcription. A qualitative interview may also consist of a short online survey, like the one I conducted in preparation for my workshop at the International Congress on Mathematical Education (ICME-13).

Obviously, the different types of qualitative data are not as easy to analyze as the numbers in a quantitative data matrix. Numerous analytical methods have been developed in qualitative research, among them the well-proven method of qualitative content analysis.

8.2 Key Points of Qualitative Content Analysis

What are the key points of the qualitative content analysis method? Regardless of which variant of QCA is used, the focus will always be on working with categories (codes) and developing a category system (coding frame). What Berelson formulated in 1952 for quantitative content analysis still applies today, both to quantitative and qualitative content analysis:

Content analysis stands or falls by its categories (…) since the categories contain the substance of the investigation, a content analysis can be no better than its system of categories. (Berelson 1952 , p. 147)

Categories are therefore of crucial importance for effective research, not only in their role as analysis tools, but also insofar as they form the substance of the research and the building blocks of the theory the researchers want to develop. That raises the question ‘What are categories?’—or more precisely, ‘What are categories in the context of empirical social research?’ Answering this question is by no means easy and there are at least two ways of doing so. The first way can be described as phenomenological : Kuckartz ( 2016 , pp. 31–39) focuses on the use of this term in the practice of empirical social research, i.e., drawing attention to what is called a category in empirical social research. The result of this analysis is a very diverse spectrum, whereby several different types of categories can be distinguished in social science research literature (ibid., pp. 34–35):

Factual categories denote actual or supposed objective circumstances such as ‘length of training’ or ‘occupation’.

Thematic categories refer to certain topics, arguments, schools of thought etc. such as ‘inclusion’, ‘environmental justice’ or ‘Ukrainian conflict’.

Evaluative categories are related to an evaluation scale—usually ordinal types, for example the category ‘helper syndrome’ with the characteristics ‘not pronounced’, ‘somewhat pronounced’ and ‘pronounced’. For evaluative categories, it is the researchers who classify the data according to predefined criteria.

Analytical categories are the result of intensive analysis of the data, i.e., these categories move away from the description of the data, for example by means of thematic categories.

Theoretical categories are subspecies of analytical categories that refer to an existing theory, such as Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior, Ainsworth’s attachment theory, or Foucault’s analysis of power.

Natural categories , also called “in vivo codes” (Charmaz 2006 , p. 56; Kuckartz 2014 , p. 23), are terms used by the actors in the field.

Formal categories denote formal characteristics of an analysis unit, e.g., the length of time in an interview.

The above list is not complete; there are many more types of categories and corresponding methods of coding (Saldana 2015 ).

A second way of answering the question ‘What is a category?’ can be described as conceptual and historical; this way leads us far back into the history of philosophy. The conceptual historical view of the term, originating from ancient Greece, starts with Greek philosophy more than 2000 years ago. Plato and Aristotle already dealt with categories—Aristotle even in an elaboration of the same term (“categories”). The study of categories runs through Western philosophy from Plato and Kant to Peirce and analytical philosophy. The philosophers are by no means in agreement on the concept of categories, but a discussion of the differences between the different schools would far exceed the scope of this paper; Instead, reading the mostly very extensive contributions on the terms ‘category’ and ‘category theory’ in the various lexicons of philosophy is recommended. Categories are basic concepts of cognition; they are—generally speaking—a commonality between certain things: a term, a heading, a label that designates something similar under certain aspects. Categories also play this role in content analysis, as the following quote from the Content Analysis textbook of Früh ( 2004 ) demonstrates:

The pragmatic sense of any content analysis is ultimately to reduce complexity from a certain research-led perspective. Text sets are described in a classifying manner with regard to characteristics of theoretical interest. In this reduction of complexity, information is necessarily lost: On the one hand, information is lost due to the suppression of message characteristics that are present in the examined texts but are not of interest in connection with the present research question; on the other hand, information is lost due to the classification of the analyzed message characteristics. According to specified criteria, some of them are each considered similar to one another and assigned to a certain characteristic class or a characteristic type, which is called ‘category’ in the content analysis. The original differences in meaning of the message characteristics uniformly grouped in a category shall not be taken into account. (p. 42, translated by the author)

But how does qualitative content analysis arrive at its categories, the basic building blocks for forming theory? There are three principal ways to develop categories:

Concept-driven (‘deductive’) development of categories; in this case the categories

are derived from a theory or

derived from the literature (the current state of research) or

derived from the research question (e.g. directly related to an interview guide)

Data-driven (‘inductive’) development of categories; the characteristics here are

the step-by-step procedure,

the method of open coding until saturation occurs,

the continuous organization and systematization of the formed codes, and

the development of top-level codes and subcodes at different levels.

Mixing a concept-driven and data-driven development of codes:

The starting point here is usually a coding frame with deductively formed codes and

the subsequent inductive coding of all data coded with a specific main category.

The terms deductive and inductive are often used for the concept-driven and data-driven approaches, respectively. However, the use of the term ‘deductive’ is rather problematic in this context: In scientific logic, the term ‘inductive’ refers to the abstract conclusion from what has been observed empirically to a general rule or a law; this has little to do with the formation of categories based on empirical data. The situation is similar with the term ‘deductive’: In scientific logic, the deductive conclusion is a logical consequence of its premises; the formation of categories based on the state of research, a theory, or an advanced hypothesis is very different. Categories do not necessarily emerge from a systematic literature review or from a research question. Due to its skid resistance, however, the word pair ‘inductive-deductive’ will probably remain in the language theorem of empirical social research or the formation of categories for a long time to come. Nevertheless, I try to avoid the terms inductive and deductive, and—like Schreier ( 2012 , p. 84)—prefer the terms ‘data-driven’ and ‘concept-driven’ for these different approaches to the formation of categories.

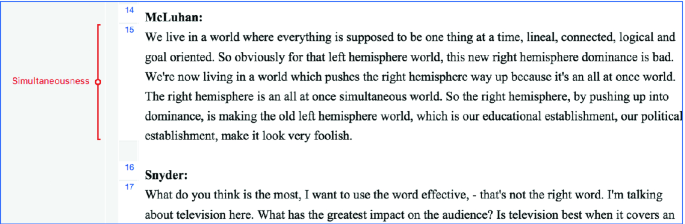

The decisive action in QCA is the coding of the data, i.e. a precisely defined part of the material is selected, and a category is assigned. As shown in the following figure, this may be a passage from an interview. Here, paragraph 15 of the text was coded with the code Simultaneousness (Fig. 8.1 ).

Text passage with a coded text segment

The individuals who perform this segmentation and coding of the data are referred to as coders. In this context, we also speak of “inter- and intracoder agreement” (reliability) (Krippendorff 2012 ; Kuckartz 2016 ; Schreier 2012 ). In quantitative content analysis, the units to be coded are usually defined in advance and referred to as coding units. In qualitative content analysis, on the other hand, coding units are not usually defined in advance; they are created by the coding process.

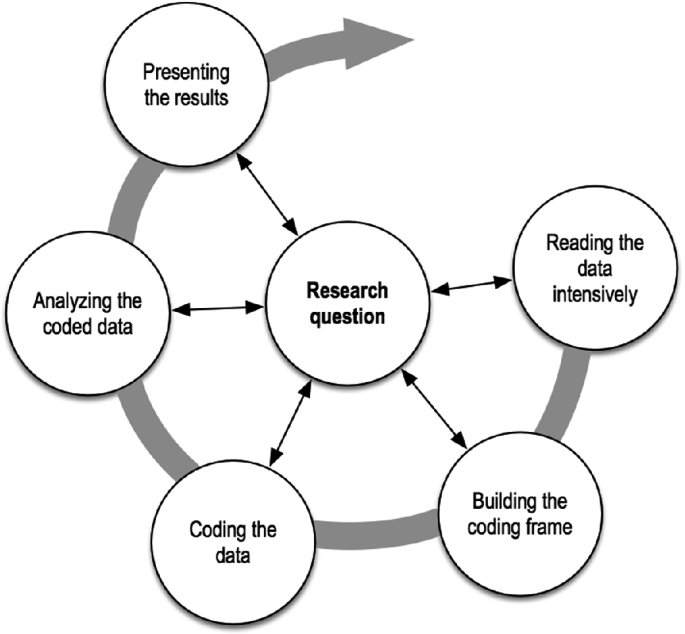

The general workflow of a qualitative content analysis is in Fig. 8.2 . In all variants the research question plays the central role in this method: It provides the perspective for the textual work necessary at the beginning, that is, the intensive reading and study of the texts (Kuckartz 2016 , p. 45). For qualitative methods, it is common for the individual analysis phases to be carried out on a circular basis. This also applies to QCA: The creation of categories and subcategories and the coding of the data can take place in several cycles. Saldana ( 2015 ) speaks of first cycle coding and second cycle coding, for example. The number of cycles is not fixed, and only in rare cases would one get by with just a single cycle.

The five phases of qualitative content analysis

Once all the data have been coded with the final category frame, a systematization and structuring of all the relevant data in view of the research questions at hand will have been achieved. Table 8.2 illustrates a model of such a thematic matrix. It is similar to the quantitative data matrix shown in Fig. 8.2 , but instead of containing numbers, the cells of the matrix now contain text excerpts coded with the respective corresponding category.

The further analysis of the matrix can now take two directions: If you look at columns, you can examine certain topics. These forms of analysis can be described as ‘category-based’. Looking at the rows, you can focus on cases (people) and carry out a ‘case-oriented analysis’.

Category-based analyses can focus on a specific category or even consider several categories simultaneously. For example, the statements made by the research participants can be contrasted between two or across several topics. Such complex analyses can lead to very rich descriptions or to the determination of influencing factors and effects, which can then be displayed in a concept map. Case-oriented analyses allow you to identify similarities between cases, identify extreme cases, and form types. Methods of consistently comparing and contrasting cases can be used to this end. For example, if you have determined a typology, you can then visualize it as a constellation of clusters and cases.

8.3 The Analysis Process in Detail

The example used in the following is a short online survey conducted in preparation for the ‘Workshop on qualitative text analysis’ as part of the ICME 13. The aim of the survey was to provide an overview of the research needs of the participants and their level of knowledge. In other words, its aim was descriptive and not about the development of hypotheses or a theory. In this online interview, I asked the following five questions and asked the participants to write their responses directly below the questions. Table 8.3 contains the resulting qualitative data.

Typically, QCA consists of six steps

Step 1: Preparing the data, initiating text work

Step 2: Forming main categories corresponding to the questions asked in the interview

Step 3: Coding data with the main categories

Step 4: Compiling text passages of the main categories and forming subcategories inductively on the material; assigning text passages to subcategories

Step 5: Category-based analyses and presenting results

Step 6: Reporting and documentation.

Since the purpose of the survey in this case was to get an overview of the relevant interests of the workshop participants and to tailor the workshop to their needs, the last step was omitted. There was no need for reporting and documentation.

The first phase consists of preparing of the data and conducting an initial read-through the responses; the analysis of this short survey did not require extensive interpretation of the responses. Since respondents used different fonts and font sizes in their e-mails, these had to be standardized first when preparing the data. In addition, the overall formatting was also adjusted to render it more uniform across responses. This would not have been absolutely necessary for the analysis, but without this preparation, later compilations of coded text passages might have looked rather chaotic.

In the second phase of QCA, categories are formed. When analyzing data obtained through an online survey, it is best to create a set of main categories based on the questions asked. In this analysis, the following five categories were formed for the first coding cycle:

Motives and goals

Experience with QCA

Specific questions about QCA

Experience with QDAS ( Q ualitative d ata a nalysis s oftware)

Academic discipline.

Since the questions in the online survey were numbered, the numbers were retained for better orientation, but they could have been dispensed with without any problems.

According to the differentiation of categories laid out earlier in this paper, the categories Motives and goals and Specific questions about QCA are thematic categories. Category 5 Academic Discipline is a factual code. The other two categories Experience with QCA and Experience with QDAS are about the experiences with the method and with QDA software. If the researcher is interested in the extent of participants’ experience, both categories are evaluative categories; alternatively, if the specific type of experience is the primary point of interest, the categories are thematic. Since the aim of this survey was to get an overview of the level of knowledge and practical experience of the respondents, an overview was sufficient; detailed knowledge of the types of experience the participants had gained was not absolutely necessary. Reading the responses also demonstrated that the respondents understood the question in this sense and that in most cases no specific details were provided. In any case, working with software like MAXQDA guarantees that you can always return to the original texts should this be useful or necessary during the course of the analysis.

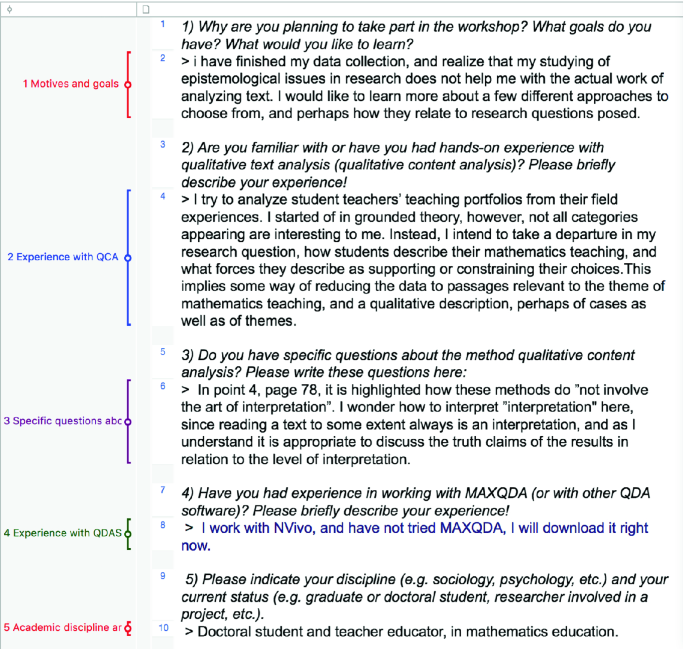

In the third phase of the analysis, the corresponding text segments are coded with the five main categories. Figure 8.3 shows a screenshot of the software MAXQDA after this first cycle of coding was performed on the survey responses. The assignments of the codes are displayed to the left of the corresponding text sections.

Display of a text with code assignments after the first cycle of coding

In the following fourth phase of the analysis, the coding frame is developed further. To do this, all the text passages coded with one of the main categories are first compiled, a procedure which is also referred to as retrieval . Subcodes are then developed directly in the relation to this data—in other words, the creation of categories is data-driven. This process is described in the following with regard to the first main category Motives and goals :

The category Motives and goals coded the responses to the question regarding what the participants wanted to learn in the workshop. First, all text passages to which this category was assigned were compiled. Then each of these text passages was coded a second time. This was done with a procedure similar to that of open coding in Grounded Theory (Strauss and Corbin 1990 ). In this case, the codes were short sequences of words that described what the participants wanted to learn:

analyze mathematics textbook curricula

learn type-building analysis

analyze e-portfolios and group discussions

analyze responses to open-ended questions

learn more about different research methods

how to establish credibility in practice

learn more about rigor within the process and how to ensure its validity

the role of reliability coefficients

insight into conducting qualitative research

learn about the QCA method

how to code video transcripts

how to take the richness of data into account (not only numbers)

analyze large numbers of open questions

learn more about a few different approaches to choose from

searching for a suitable method to analyze the interviews

interesting for me to see how colleagues are working.

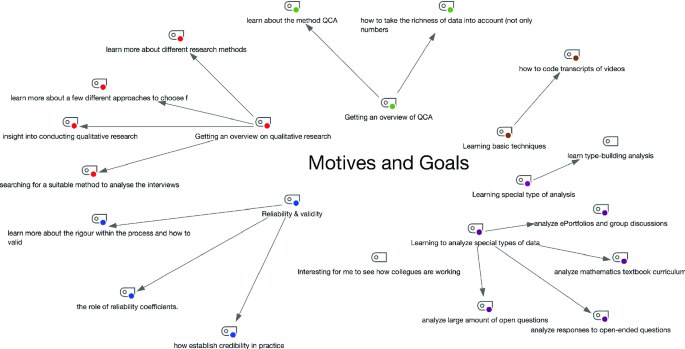

As part of the software MAXQDA there is a module called “Creative Coding” that allows you to visually group codes obtained through the open coding method. After arranging the open codes, seven subcategories were created for the category “Motives and Objectives”, namely

Getting an overview of qualitative research

Getting an overview of QCA

Learning basic techniques

Learning about special type of analysis

Reliability and validity

Learning to analyze special types of data

Interesting for me to see how colleagues are working.

Figure 8.4 shows a visual display of the category formation; the original statements are assigned to the respective category. It turns out that many participants in the workshop were mainly interested in obtaining an overview of qualitative content analysis and qualitative research in general. The graph also implicitly illustrates the differences between a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the responses: Four participants (a comparatively large proportion) wanted to learn how to analyze specific types of data, but a closer look at the details, that is, the qualitative dimension, reveals that the types of data the respondents had in mind were completely different.

Visualization of the motives grouped into subcategories

Once the subcategories have been created, all the data coded with the main category Motives and goals must be coded a second time. This is also known as the second coding cycle. In this sample survey, all the coded text passages were included in the formation of the subcategories due to the relatively small sample. In the case of small sample sizes like this, the Creative Coding module automatically reassigns the subcategories. In the case of larger samples, however, category formation will usually be carried out only with a subsample and not with all the data, or the process of open coding will be performed only until the system of subcategories appears saturated and no further subcategories need to be redefined. Then, of course, the data that have not been considered up to this point must still be coded in line with the final category system.

The two categories Experience with QCA and Experience with QDAS were used to code the text passages in which the respondents reported on their experience with the QCA method and the use of QDA software. For the purposes of preparing the workshop as described above, the analysis should address only whether participants had prior experience and how extensive this experience was. An evaluative category with the values ‘yes’, ‘partial’, ‘no’ was therefore defined.

For the third main category, Specific questions about QCA , no subcategories were formed, since the questions formulated by the participants had to be retained in their wording to answer them in the workshop. However, the questions asked were sorted by topic, and essentially identical questions were summarized.

For category 5, Academic discipline , subcategories were initially formed according to the disciplines mentioned by the respondents. However, it quickly transpired that almost all participants came from the field of mathematics education and that there were only a few individual cases from other fields such as development psychology or primary school teacher (see Fig. 8.5 ). These individual cases were combined into the subcategory others for the final category system, so that ultimately only two subcategories were formed.

Main category “Academic discipline and status” with subcategories

After the main categories have been processed in this way—five in the case of this survey—the fifth phase ‘Category-based analyses and presenting results’ can begin. However, it should be clear that in the fourth phase of the development of the category system, an extensive amount of analytical work has already being carried out. The identification of the different motive types represents an analytical achievement in itself and is, at the same time, the foundation of the corresponding category-based analysis in phase 5. The category Motives and goals was of central importance in this survey. In addition to identifying the various motives, both quantitative and qualitative analyses can now be carried out. Quantitatively, we can determine how many people expressed which motives in their statement. Of course, it is quite possible for someone to have expressed several motives. In terms of a qualitative analysis, we can ask what is behind these categories in greater detail. In relation to the subcategory Learning to analyze special types of data , for example, we could ask which special data types the respondents had in mind here.

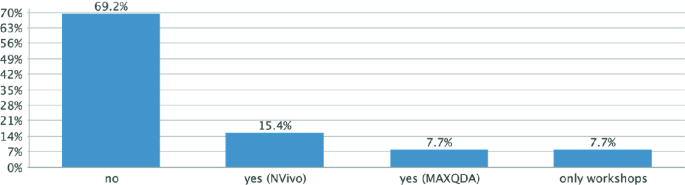

The category-based analysis always offers the option of focusing on qualitative and/or quantitative aspects. A frequency analysis of the category Experience with QDAS shows that the vast majority of participants have not yet had any practical experience with QDA software (see Fig. 8.6 ).

Bar chart of the category “Experiences with QDA software”

The question concerning their experience with text analysis methods presents a somewhat different picture. Quantitatively, we can see that more people are experienced in this regard, while the more detailed qualitative view reveals that this experience mainly involved the Grounded Theory method. It is interesting to compare the two categories that deal with experience. Table 8.4 contains an excerpt from such a comparison between five people.

There are also many further possibilities regarding the analysis of interrelationships that can be carried out in this fifth phase. For example, the connection between motives and goals, and previous knowledge and experience, can be examined. In relation to the specific questions asked by respondents in the survey, one could create a cross table (or “crosstab”) in which the questions asked by the experienced group are compared with the questions asked by those with no experience.

There are many other analysis options for larger studies than those presented for the small online survey. Qualitative content analysis is not a method that is always applied in the same way regardless of the data or research questions at hand. Although it is a systematic procedure, it nonetheless offers a flexibility that allows you to adapt it to the respective requirements of a project. There are other analytical possibilities in this regard, which were not mentioned in the above description. Among these, two should be highlighted in particular, namely, the possibility of paraphrasing text passages and the possibility of creating thematic summaries.

Paraphrasing passages of text can be understood in its everyday sense, namely, that researchers reformulate these text passages in their own words. This can be a very useful tool for category development. This technique is especially recommended for beginners, as it forces them to read the text line by line, interpret it to gain a thorough understanding, and then record it in their own words. It is certainly too time-consuming in most cases to edit all texts in this way but paraphrasing a selected subset of texts can sharpen your analytical view and be a valuable intermediate step in the development of a meaningful category system. Moreover, these paraphrases can then be sorted, particularly significant paraphrases can be combined, and gradually more abstract and theoretically rich categories can be formed.

In contrast to paraphrasing texts, formulating thematic summaries assumes that the texts have already been coded. In this approach, all the text passages coded in regard to a specific topic are read for each case and a thematic summary is written for each person. Usually, there is a huge gap between a category and the amount of original text assigned to it in the case of longer qualitative interviews, such as narrative interviews. On the one hand there is a relatively short code, such as ‘Environmental behavior in relation to nutrition’, and on the other there are numerous passages of varying length in which a respondent says something on this subject. A thematic summary summarizes all these passages as said by a certain person from the perspective of the research question. This means that the text is not repeated, but rather edited conceptually. Summaries thus create a second level between the original text and the categories and concepts. They also enable complex analyses to be carried out in which several categories are compared or the statements of different groups (women/men, different age groups, different schooling, etc.) are contrasted. This would be nigh impossible if the original quotations were always used since the amount of text would simply be too large, and it would consequently not be possible to create case overviews. A thematic summary, on the other hand, compresses what one person has said in such a way that it can easily be included in further analyses.

A third possibility the QCA method offers is the visualization of relationships between categories. Diagrams, in the form of concept maps, can be generated in which the influencing factors, effects, and relations are visualized.

Phase 6, ‘Reporting and documentation’, is about putting the results of your analyses on paper. The research report of a project working with the QCA method is usually divided into a descriptive and an analytical section. Depending on the method and the significance of the categories, category-based analyses will be the center of attention. The case dimension, however, which is all too often neglected, should also be taken into account in the report. It is often very valuable for the recipients of the research not only to learn something about the connections between the categories, but also something about the participants, that is, the cases that are consciously selected for such a presentation. It is particularly interesting if the cases are grouped into types and the report presents cases that are representative of these types.

The category-based presentation should be illustrated with quotes from the original material. However, you should also be aware of the danger of selective plausibility, i.e., that one mainly selects quotations that clarify the alleged connections between categories, while contradictory examples are not considered. For this reason, counterexamples should always be sought and included in the report.

Category-based analysis should not be limited to a description of the results per category but should also look at the relationships between two or more categories. In other words, you should move from the initial description to the development of a theory.

8.4 Summary and Conclusions

This chapter presents a method for the methodically controlled analysis of texts in empirical research. To conclude, therefore, the characteristics of the QCA method are concisely summarized:

The focus of the QCA method is on the categories with which the data are coded.

The categories of the final coding frame are described as precisely as possible and it is ensured that the coding procedure itself is reliable, i.e., that different coders concur in their coding.

The data must be coded completely. Complete in this sense means that all passages in the texts that are relevant to the research question are coded. It does, however, make sense to leave those parts of the data uncoded, which are outside the focus of the research question.

The codes and categories can be formed in different ways: empirically, i.e., based directly on the material, or conceptually, i.e., based on the current state of research or on a theory/hypothesis or, rather, as an implementation of the guidelines used in an interview or focus group.

The QCA method is carried out in several phases, ranging from data preparation, category building and coding—which may run in several cycles—to analysis, report writing and presenting the results. QCA therefore means more than just coding the data. Coding is an important step in the analysis, but it is ultimately a preparation for the subsequent analytical steps.

The actual analysis phase consists of summarizing the data, and constantly comparing and contrasting the data. The analysis techniques can be qualitative as well as quantitative. The qualitative analysis may, for example, consist of comparing the statements of certain groups (for instance according to their characteristics, e.g., socio-demographic characteristics) on certain topics. Differences and similarities are identified and summarized in a report. Quantitative analyses may, on the other hand, consist of comparing the frequency of certain categories and/or subcategories for certain groups.

Summary tables and diagrams (e.g., concept maps) can play an important role in the analysis. A good example of a presentation in table form would be a case overview of selected research participants (or groups), in which their statements on certain topics, their judgements and variable values are displayed. An example of a concept map would be a diagram of the determined causal effects of different categories.

Visualizations can also have a diagnostic function in QCA—similarly to imaging procedures in medicine. For example, a ‘cases by categories’ or ‘categories by categories’ display can help identify patterns in the data and indicate which categories are particularly frequently or particularly rarely associated with certain other categories.

When analyzing texts, you should keep in mind that you are working in the field of interpretation. It can be assumed that texts or statements could be interpreted differently. Instead of adopting a constructivist ‘anything goes’ approach, the QCA method tries to reach a consensus—as far as this is possible—on the subjective meaning of statements and tries to define the categories formed or used by it so precisely that an intersubjective agreement can be achieved in the application of the categories.

Group processes play an important role in this process of achieving the necessary level of agreement. Divergent assignments to categories are discussed as a team and should result in an improvement of the category definitions. Categories for which no agreement can be reached in the coding of relevant points in the data must be excluded from the analysis. Content analysis stands and falls by its categories. An analysis with the help of categories that are interpreted and applied differently in the research team, does not make sense.

QCA does not claim to be the best method but recognizes that it has its limits (the interpretation barrier) and that its results have to face comparison with those of competing methods.

The systematic approach of QCA is multidisciplinary and can be applied in many disciplines, including mathematics education (Schwarz 2015 ). This method is particularly appropriate when working with clearly formulated research questions, because these questions play the central role in this method. Indeed, in every phase of the analysis there is a strong reference to the questions leading the research. One strength of QCA is that it can be used both to describe social phenomena and to develop theories or test hypotheses (Hopf 2016 , pp. 155–166).

Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in communication research . Glencoe: Free Press.

Google Scholar

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory . Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Früh, W. (2004). Inhaltsanalyse. Theorie und Praxis (5th ed.). Konstanz: UVK.

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis . Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Book Google Scholar

Hopf, C. (2016). In W. Hopf & U. Kuckartz (Eds.), Schriften zu Methodologie und Methoden qualitativer Sozialforschung . Wiesbaden: Springer.

Krippendorff, K. H. (2012). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Kuckartz, U. (2014). Qualitative text analysis: A guide to methods, practice and using software . Los Angeles: SAGE.

Kuckartz, U. (2016). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung (3rd ed.). Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 .

Mayring, P. (2015). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical background and procedures. In A. Bikner-Ahsbahs, C. Knipping, & N. Presmeg (Eds.), Approaches to qualitative research in mathematics education. Examples of methodology and methods (pp. 365–380). Dordrecht: Springer.

Saldana, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice . Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Schwarz, B. (2015). A study on professional competence of future teacher students as an example of a study using qualitative content analysis. In A. Bikner-Ahsbahs, C. Knipping, & N. Presmeg (Eds.), Approaches to qualitative research in mathematics education. Examples of methodology and methods (pp. 381–399). Dordrecht: Springer.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Philipps-University Marburg, Marburg, Germany

Udo Kuckartz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Udo Kuckartz .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education, Universität Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

Gabriele Kaiser

Mathematics Department, Illinois State University, Normal, IL, USA

Norma Presmeg

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Kuckartz, U. (2019). Qualitative Text Analysis: A Systematic Approach. In: Kaiser, G., Presmeg, N. (eds) Compendium for Early Career Researchers in Mathematics Education . ICME-13 Monographs. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15636-7_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15636-7_8

Published : 27 April 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-15635-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-15636-7

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Analyzing Text Data

- Overview of Text Analysis and Text Mining

Choosing a Method

How much data do you need, word frequency analysis, machine learning/natural language processing, sentiment analysis.

- Library Databases

- Social Media

- Open Source

- Language Corpora

- Web Scraping

- Software for Text Analysis

- Text Data Citation

Library Data Services

Choosing the right text mining method is crucial because it significantly impacts the quality of insights and information you can extract from your text data. Each method provides different insights and requires different amounts of data, training, and iteration. Before you search for data, it is essential that you:

- identify the goals of your analysis

- determine the method you will use to meet those goals

- identify how much data you need for that method

- develop a sampling plan to build a data set that accurately represents your object of study.

Starting with this information in mind will make your project go more quickly and smoothly, and help you overcome a lot of hurdles such as incomplete data, too much or too little data, or problems with access to data.

More Resources:

- Content Analysis Method and Examples, from Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University

- Qualitative Research Methods Overview, from Northeastern University

- O'Reilly Online Learning: Nvivo

- Sage Research Methods: NVivo

- Sage Research Methods: Atlas.ti

Before you start collecting data, think about how much data you really need. New researchers in text analysis often want to collect every source mentioning their topic, but this is usually not the best approach. Collecting so much data takes a lot of time, uses many computational resources, often goes against platform terms of service, and doesn't necessarily improve analysis.

In text analysis, an essential idea is saturation , where adding more data doesn't significantly improve performance. Saturation is when the model has learned as much as it can from the available data, and no new patterns are themes are emerging with additional data. Researchers often use experimentation and learning curves to determine when saturation occurs; you can start by analyzing a small or mid-sized dataset and see what happens if you add more data.

Once you know your research question, the next step is to create a sampling plan . In text analysis, sampling means selecting a representative subset of data from a larger dataset for analysis. This subset, called the sample, aims to capture the diversity of sentiments in the overall dataset. The goal is to analyze this smaller portion to draw conclusions about the information in the entire dataset.

For example, in a large collection of customer reviews, sampling may involve randomly selecting a subset for sentiment analysis instead of analyzing every single review. This approach saves computational resources and time while still providing insights into the overall sentiment distribution of the entire dataset. It's crucial to ensure that the sample accurately reflects the diversity of sentiments in the complete dataset for valid and reliable generalizations.

Example Sampling Plans

Sampling plans for text analysis involve selecting a subset of text data for analysis rather than analyzing the entire dataset. Here are two common sampling plans for text analysis:

Random Sampling:

- Description: Randomly select a subset of text documents from the entire dataset.

- Process: Assign each document a unique identifier and use a random number generator to choose documents for inclusion in the sample.

Stratified Sampling:

- Description: Divide the dataset into distinct strata or categories based on certain characteristics (e.g., product types, genres, age groups, race or ethnicity). Then, randomly sample from each stratum.

- Process: Divide the dataset into strata, and within each stratum, use random sampling to select a representative subset.

Remember, the choice of sampling plan depends on the specific goals of the analysis and the characteristics of the dataset. Random sampling is straightforward and commonly used when there's no need to account for specific characteristics in the dataset. Stratified sampling is useful when the dataset has distinct groups, and you want to ensure representation from each group in the sample.

Exactly How Many Sources do I need?

Determining the amount of data needed for text analysis involves a balance between having enough data to train a reliable model and avoiding unnecessary computational costs. The ideal dataset size depends on several factors, including the complexity of the task, the diversity of the data, and the specific algorithms or models being used.

- Task Complexity: If you are doing a simple task, like sentiment analysis or basic text classification, a few dozen articles might be enough. More complex tasks, like language translation or summarization, often require datasets on the scale of tens of thousands to millions.

- Model Complexity: Simple models like Naive Bayes often perform well with smaller datasets, whereas complex models, such as deep learning models with many parameters, will require larger datasets for effective training.

- Data Diversity: Ensure that the dataset is diverse and representative of the various scenarios the model will encounter. A more diverse dataset can lead to a more robust and generalizable model. A large dataset that is not diverse will yield worse results than a smaller, more diverse dataset.

- Domain-Specific Considerations: Sometimes there is not a lot of data available, and it is okay to make do with what you have!

Start by taking a look at articles in your field that have done a similar analysis. What approaches did they take? You can also schedule an appointment with a Data Services Librarian to get you started.

More Readings on Sampling Plans for Text Analysis:

- How to Choose a Sample Size in Qualitative Research, from LinkedIn Learning (members of the GW community have free access to LinkedIn Learning using their GW email account)

- Sampling in Qualitative Research , from Saylor Academy

- Lowe, A., Norris, A. C., Farris, A. J., & Babbage, D. R. (2018). Quantifying Thematic Saturation in Qualitative Data Analysis. Field Methods, 30(3), 191-207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X17749386

Software for Word Frequency Analysis

- NVivo via GW's Virtual Computer Lab NVivo is a software package used for qualitative data analysis. It includes tools to support the analysis of textual data in a wide array of formats, as well as and audio, video, and image data. NVivo is available through the Virtual Computer Lab. Faculty and staff may find NVivo available for download from GW's Software Center.

- Analyzing Word and Document Frequency in R This chapter explains how to use tidy to analyze word and document frequency using Tidy Data in R.

- word clouds in R R programming functionality to create pretty word clouds, visualize differences and similarities between documents, and avoid over-plotting in scatter plots with text.

- ATLAS.ti Trial version of qualitative analysis workbench for processing text, image, audio, and video data. (Note: Health science students may have access to full version through Himmelfarb Library)

Related Tools Available Online

- Google ngram Viewer When you enter phrases into the Google Books Ngram Viewer, it displays a graph showing how those phrases have occurred in a corpus of books (e.g., "British English", "English Fiction", "French") over the selected years.

- HathiTrust This link opens in a new window HathiTrust is a partnership of academic and research institutions, offering a collection of millions of titles digitized from libraries around the world. To log in, select The George Washington University as your institution, then log in with your UserID and regular GW password.

- Voyant Voyant is an online point-and-click tool for text analysis. While the default graphics are impressive, it allows limited customizing of analysis and graphs and may be most useful for exploratory visualization.

Related Library Resources

- HathiTrust and Text Mining at GWU HathiTrust is an international community of research libraries committed to the long-term curation and availability of the cultural record. Through their common efforts and deep commitment to the public good, the libraries support the teaching and learning activities of the faculty, students or researchers at their home institutions, and the scholarly needs of the broader public as well.

- HathiTrust+Bookworn From the University of Illinois Library: HathiTrust+Bookworm is an online tool for visualizing trends in language over time. Developed by the HathiTrust Research Center using textual data from the HathiTrust Digital Library, it allows you to track changes in word use based on publication country, genre of works, and more.

- Python for Natural Language Processing A workshop offered through GW Libraries on natural language processing using Python.

- Text Mining Tutorials in R A collection of text mining course materials and tutorials developed for humanists and social scientists interested to learn R.

- Oxford English Dictionary This link opens in a new window The Oxford English Dictionary database will provide a word frequency analysis over time, drawing both from Google ngrams and the OED's own databases.

Example Projects Using Word Frequency Analysis

Robinson, J. S. and D. (n.d.). 3 Analyzing word and document frequency: Tf-idf | Text Mining with R . Retrieved November 21, 2023, from https://www.tidytextmining.com/tfidf.html

- Zhang, Z. (n.d.). Text Mining for Social and Behavioral Research Using R . Retrieved November 21, 2023, from https://books.psychstat.org/textmining/index.html

- Exploring Fascinating Insights with Word Frequency Analysis In the realm of data analysis, words hold immense power. They convey meaning, express ideas, and shape our understanding of the world. In this article, we’ll explore the fascinating world of textual data analysis by examining word frequencies. By counting the occurrence of words in a text, we can uncover interesting insights and gain a deeper understanding of the underlying themes and patterns. Join us on this word-centric journey as we dive into the realm of word frequency analysis using Python.

Machine learning for text analysis is a technology that teaches computers to understand and interpret written language by exposing them to examples. There are two types of machine learning for text analysis: supervised learning, in which a human helps to train the computer to detect patterns, and unsupervised learning, which enables computers to automatically categorize, analyze, and extract information from text without needing explicit programming.

One type of machine learning for text analysis is Natural Language Processing (NLP). NLP for text analysis is a field of artificial intelligence that involves the development and application of algorithms to automatically process, understand, and extract meaningful information from human language in textual form. NLP techniques are used to analyze and derive insights from large volumes of text data, enabling tasks such as sentiment analysis, named entity recognition, text classification, and language translation. The aim is to equip computers with the capability to comprehend and interpret written language, making it possible to automate various aspects of text-based information processing.

Software for Natural Language Processing

- NLTK for Python NLTK is a leading platform for building Python programs to work with human language data. It provides easy-to-use interfaces to over 50 corpora and lexical resources such as WordNet, along with a suite of text processing libraries for classification, tokenization, stemming, tagging, parsing, and semantic reasoning, wrappers for industrial-strength NLP libraries, and an active discussion forum.

- scikit Simple and efficient tools for predictive data analysis, using Python.

Related Resources Available Online

- [Large Language Models] LLMs in Scientific Research

- HathiTrust and Text Mining at GWU Information on text data mining using HathiTrust

- Social Feed Manager Social Feed Manager software was developed to support campus research about social media including Twitter, Tumblr, Flickr, and Sina Weibo platforms. It can be used to track mentions of you or your articles and other research products for the previous seven days and on into the future.. Email [email protected] to get started with Social Feed Manager or to schedule a consultation

Example Projects using Natural Language Processing

- Redd D, Workman TE, Shao Y, Cheng Y, Tekle S, Garvin JH, Brandt CA, Zeng-Treitler Q. Patient Dietary Supplements Use: Do Results from Natural Language Processing of Clinical Notes Agree with Survey Data? Medical Sciences . 2023; 11(2):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci11020037

- Nguyen D, Liakata M, DeDeo S, Eisenstein J, Mimno D, Tromble R, Winters J. How We Do Things With Words: Analyzing Text as Social and Cultural Data. Front Artif Intell. 2020 Aug 25;3:62. doi: 10.3389/frai.2020.00062.

Sentiment analysis is a method of analyzing text to determine whether the emotional tone or sentiment expressed in a piece of text is positive, negative, or neutral. Sentiment analysis is commonly used in businesses to gauge customer feedback, social media monitoring, and market research.

Software for Sentiment Analysis

- Sentiment Analysis using NLTK for Python NLTK is a leading platform for building Python programs to work with human language data. It provides easy-to-use interfaces to over 50 corpora and lexical resources such as WordNet, along with a suite of text processing libraries for classification, tokenization, stemming, tagging, parsing, and semantic reasoning, wrappers for industrial-strength NLP libraries, and an active discussion forum.

- Sentiment Analysis with TidyData in R This chapter shows how to implement sentiment analysis using tidy data principles in R.

- Tableau Tableau works with numeric and categorical data to produce advanced graphics. Browse the Tableau public gallery to see examples of visuals and dashboards. Tableau offers free one-year Tableau licenses to students at accredited academic institutions, including GW. Visit https://www.tableau.com/academic/students for more about the program or to request a license.

- Qualtrics Text iQ Qualtrics is a powerful tool for collecting and analyzing survey data. Qualtrics Text iQ automatically performs sentiment analysis on collected data.

Related Resources Available Online

- finnstats. (2021, May 16). Sentiment analysis in R | R-bloggers. https://www.r-bloggers.com/2021/05/sentiment-analysis-in-r-3/

Example Projects Using Sentiment Analysis

- Duong, V., Luo, J., Pham, P., Yang, T., & Wang, Y. (2020). The Ivory Tower Lost: How College Students Respond Differently than the General Public to the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM), 126–130. https://doi.org/10.1109/ASONAM49781.2020.9381379

- Ali, R. H., Pinto, G., Lawrie, E., & Linstead, E. J. (2022). A large-scale sentiment analysis of tweets pertaining to the 2020 US presidential election. Journal of Big Data, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-022-00633-z

- << Previous: Overview of Text Analysis and Text Mining

- Next: Finding Text Data >>

- Last Updated: Nov 6, 2024 3:02 PM

- URL: https://libguides.gwu.edu/textanalysis

- Privacy Policy

Home » Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Qualitative research is a method of inquiry that seeks to understand human experiences, behaviors, and interactions by exploring them in-depth. Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on numerical data, qualitative research delves into meanings, perceptions, and subjective experiences. It is widely used in fields such as sociology, psychology, education, healthcare, and business to uncover insights that are difficult to capture through numerical data.

This article explores the methods of qualitative research, types of qualitative analysis, and a comprehensive guide to conducting a qualitative study.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a non-numerical method of data collection and analysis that focuses on understanding phenomena from the perspective of participants. It prioritizes depth over breadth and aims to explore the “why” and “how” behind human behaviors and social phenomena.

For example, qualitative research might examine how individuals cope with chronic illness by conducting interviews to explore their experiences and emotions in detail.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

- Exploratory Nature: Focuses on exploring new areas of study or understanding complex phenomena.

- Contextual Understanding: Emphasizes the importance of context in interpreting findings.

- Subjectivity: Values participants’ perspectives and experiences as central to the research.

- Flexibility: Allows for adjustments to research design based on emerging insights.

- Rich Data: Produces detailed and nuanced descriptions rather than numerical summaries.

Methods of Qualitative Research

1. interviews.

Interviews involve one-on-one conversations between the researcher and participants to gather in-depth insights.

- Types: Structured, semi-structured, or unstructured interviews.

- Example: Interviewing teachers to understand their experiences with online education.

2. Focus Groups

Focus groups consist of facilitated discussions with small groups of participants to explore shared experiences or perspectives.

- Example: Conducting a focus group with patients to understand their satisfaction with healthcare services.

3. Observation

Observation involves studying participants in their natural environment to capture behaviors, interactions, and contexts.

- Types: Participant observation (researcher participates) and non-participant observation (researcher observes without involvement).

- Example: Observing interactions in a classroom to understand teaching dynamics.

4. Case Studies

Case studies provide an in-depth examination of a single individual, group, event, or organization.

- Example: Analyzing the impact of a leadership change within a specific company.

5. Ethnography

Ethnography focuses on studying cultural practices and social norms by immersing the researcher in the community.

- Example: Exploring the cultural traditions of an indigenous group through prolonged fieldwork.

6. Document Analysis

Document analysis involves analyzing written or visual materials, such as reports, diaries, photographs, or social media posts.

- Example: Reviewing company policies to understand workplace diversity practices.

7. Narrative Research

Narrative research examines personal stories and experiences to understand individual perspectives.

- Example: Analyzing the life stories of refugees to explore their resilience and adaptation processes.

Types of Qualitative Data Analysis

1. thematic analysis.

Thematic analysis involves identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within qualitative data.

- Steps: Familiarization, coding, theme identification, and interpretation.

- Example: Analyzing interview transcripts to uncover themes related to work-life balance.

2. Content Analysis

Content analysis systematically categorizes textual or visual data to identify patterns and themes.

- Example: Analyzing social media comments to explore public opinions on environmental policies.

3. Grounded Theory

Grounded theory focuses on developing a theory grounded in the data collected.

- Steps: Open coding, axial coding, and selective coding.

- Example: Developing a theory about customer satisfaction based on retail feedback.

4. Narrative Analysis

Narrative analysis examines the structure and content of personal stories to uncover meaning.

- Example: Analyzing interviews with survivors of natural disasters to understand coping strategies.

5. Discourse Analysis

Discourse analysis explores how language is used in specific contexts to construct meaning and social realities.

- Example: Analyzing political speeches to identify persuasive strategies.

6. Framework Analysis

Framework analysis uses a structured approach to analyze data within a thematic framework.

- Example: Evaluating healthcare professionals’ experiences with new policies using predefined themes.

7. Phenomenological Analysis

Phenomenological analysis focuses on understanding the lived experiences of participants.

- Example: Exploring the experiences of first-time parents to understand emotional transitions.

Guide to Conducting Qualitative Research

Step 1: define the research problem.

Clearly articulate the purpose of your study and the research questions you aim to address.

- Example: “What are the experiences of remote workers during the COVID-19 pandemic?”

Step 2: Choose a Research Method

Select a method that aligns with your research objectives and the nature of the phenomenon.

- Example: Conducting semi-structured interviews to gather personal insights.

Step 3: Identify Participants

Choose participants who can provide rich and relevant data for your study.

- Example: Selecting remote workers from diverse industries to capture varied perspectives.

Step 4: Collect Data

Use the chosen method to gather detailed and context-rich data.

- Example: Conducting interviews via video calls and recording responses for analysis.

Step 5: Analyze Data

Apply an appropriate qualitative analysis method to identify patterns, themes, or insights.

- Example: Using thematic analysis to group common challenges faced by remote workers.

Step 6: Interpret Findings

Contextualize your findings within the existing literature and draw meaningful conclusions.

- Example: Comparing your findings on remote work challenges with studies conducted pre-pandemic.

Step 7: Present Results

Communicate your results clearly, using direct quotes, narratives, or visualizations to support your findings.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

- Rich Insights: Provides deep understanding of complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Adapts to the research context and emerging findings.

- Contextual Detail: Captures the nuances of participants’ experiences and environments.

- Exploratory Nature: Ideal for exploring new or poorly understood topics.

Challenges of Qualitative Research

- Time-Intensive: Data collection and analysis can be lengthy processes.

- Subjectivity: Risk of researcher bias influencing data interpretation.

- Generalizability: Findings are context-specific and may not apply universally.

- Data Management: Handling and analyzing large volumes of qualitative data can be challenging.

Applications of Qualitative Research

- Healthcare: Understanding patient experiences with chronic illnesses.

- Education: Exploring teacher perceptions of new classroom technologies.

- Marketing: Investigating consumer attitudes toward a brand.

- Social Work: Analyzing community responses to social programs.

- Psychology: Examining coping mechanisms among individuals facing trauma.

Qualitative research is a powerful method for exploring the human experience and understanding complex social phenomena. By employing diverse methods such as interviews, focus groups, and ethnography, and using robust analytical techniques, qualitative researchers uncover rich, detailed insights that are essential for addressing real-world challenges. Although it requires careful planning, execution, and interpretation, qualitative research offers unparalleled depth and contextual understanding, making it indispensable across disciplines.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches . Sage Publications.

- Flick, U. (2018). An Introduction to Qualitative Research . Sage Publications.

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2017). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research . Sage Publications.

- Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation . Jossey-Bass.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology . Qualitative Research in Psychology.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Quasi-Experimental Research Design – Types...

Exploratory Research – Types, Methods and...

Ethnographic Research -Types, Methods and Guide

Descriptive Research Design – Types, Methods and...

Focus Groups – Steps, Examples and Guide

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Nov 21, 2013 · Qualitative text analysis is ideal for these types of data and this textbook provides a hands-on introduction to the method and its theoretical underpinnings. It offers step-by-step instructions for implementing the three principal types of qualitative text analysis: thematic, evaluative, and type-building.

Mar 26, 2024 · It is a cornerstone of qualitative research in disciplines such as linguistics, media studies, sociology, and literary analysis. By delving into the meanings, structures, and contexts of written or spoken texts, textual analysis provides insights into communication, culture, and human interaction.

Apr 27, 2019 · Thematic analysis, often called Qualitative Content Analysis (QCA) in Europe, is one of the most commonly used methods for analyzing qualitative data (Guest et al. 2012; Kuckartz 2014; Mayring 2014, 2015; Schreier 2012). This chapter presents the basics of this systematic method of qualitative data analysis, highlights its key characteristics ...

1.2 Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Research You would expect that a book on the analysis of qualitative data would not only define the terms ‘qualitative data’ and ‘quantitative data’, but would also give a definition of the term ‘qualitative research’, which goes beyond ‘collection and analysis of non-numeric data’.

Nov 6, 2023 · More Readings on Sampling Plans for Text Analysis: How to Choose a Sample Size in Qualitative Research, from LinkedIn Learning (members of the GW community have free access to LinkedIn Learning using their GW email account) Sampling in Qualitative Research, from Saylor Academy; Lowe, A., Norris, A. C., Farris, A. J., & Babbage, D. R. (2018).

Mar 25, 2024 · Qualitative Research. Qualitative research is a non-numerical method of data collection and analysis that focuses on understanding phenomena from the perspective of participants. It prioritizes depth over breadth and aims to explore the “why” and “how” behind human behaviors and social phenomena.