An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Racism and Health: Evidence and Needed Research

David r williams, jourdyn lawrence, brigette davis.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Address correspondence to David R. Williams, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, 677 Huntington Avenue, 6 th floor, Boston, MA 02115 ( [email protected] )

Issue date 2019 Apr 1.

In recent decades, there has been remarkable growth in scientific research examining the multiple ways in which racism can adversely affect health. This interest has been driven in part by the striking persistence of racial/ethnic inequities in health and the empirical evidence that indicates that socioeconomic factors alone do not account for racial/ethnic inequities in health. Racism is considered a fundamental cause of adverse health outcomes for racial/ethnic minorities and racial/ethnic inequities in health. This article provides an overview of the evidence linking the primary domains of racism – structural racism, cultural racism and individual-level discrimination – to mental and physical health outcomes. For each mechanism, we describe key findings and identify priorities for future research. We also discuss evidence for interventions to reduce racism and needed research to advance knowledge in this area.

There has been steady and sustained growth in scientific research on the multiple ways in which racism can affect health and racial/ethnic inequities in health. This article provides an overview of key findings and trends in this area of research. It begins with a description of the nature of racism and the principal mechanisms -- structural, cultural and individual -- by which racism can affect health. For each dimension, we review key research findings and describe needed scientific research. We also discuss evidence for interventions to reduce racism and needed research to advance knowledge in this area. Finally, we discuss crosscutting priorities across the three domains of racism.

The patterning of racial/ethnic inequities in health was an early impetus for research on racism and health ( 139 ). First, there are elevated rates of disease and death for historically marginalized racial groups, blacks (or African Americans), Native Americans (or American Indians and Alaska Natives) and Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders, who tend to have earlier onset of illness, more aggressive progression of disease and poorer survival ( 5 , 134 ). Second, empirical analyses revealed the persistence of racial differences in health even after adjustment for socioeconomic status (SES). For example, at every level of education and income, African Americans have lower life expectancy at age 25 than whites and Hispanics (or Latinos), with blacks with a college degree or more education having lower life expectancy than whites and Hispanics who graduated from high school ( 15 ). Third, research has also documented declining health for Hispanic immigrants over time with middle-aged U.S.-born Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants resident 20 or more years in the U.S. having a health profile that did not differ from that of African Americans ( 56 ).

Racism and Health

Racism is an organized social system, in which the dominant racial group, based on an ideology of inferiority, categorizes and ranks people into social groups called “races”, and uses its power to devalue, disempower, and differentially allocate valued societal resources and opportunities to groups defined as inferior ( 13 , 140 ). Race is primarily a social category, based on nationality, ethnicity, phenotypic or other markers of social difference, which captures differential access to power and resources in society ( 133 ). Racism functions on multiple levels. The cultural agencies within a society socializes the population to accept as true the inferiority of non-dominant racial groups leading to negative normative beliefs (stereotypes) and attitudes (prejudice) toward stigmatized racial groups which undergird differential treatment of members of these groups by both individuals and social institutions ( 13 , 140 ). A characteristic of racism is that its structure and ideology can persist in governmental and institutional policies in the absence of individual actors who are explicitly racially prejudiced ( 7 ).

As a structured system, racism interacts with other social institutions, shaping them and being re-shaped by them, to reinforce, justify and perpetuate a racial hierarchy. Racism has created a set of dynamic, interdependent, components or subsystems that reinforce each other, creating and sustaining reciprocal causality of racial inequities across various sectors of society ( 106 ). Thus, structural racism exists within, and is reinforced and supported by multiple societal systems, including the housing, labor and credit markets, and the education, criminal justice, economic and healthcare systems. Accordingly, racism is adaptive over time, maintaining its pervasive adverse effects through multiple mechanisms that arise to replace forms that have been diminished ( 99 , 140 ).

Racism: A Fundamental Cause of Racial/Ethnic Inequities in Health

The persistence of racial inequities in health should be understood in the context of relatively stable racialized social structures that determine differential access to risks, opportunities, and resources that drive health. We conceptualize this system of racism, chiefly operating through institutional and cultural domains, as a basic or fundamental cause of racial health inequalities ( 74 , 99 , 133 , 136 ). According to Lieberson, fundamental causes are critical causal factors that generate an outcome while surface causes are associated with the outcome but changes in these factors do not trigger changes in the outcome ( 73 ). Instead, as long as the fundamental causes are operative, interventions on surface causes only give rise to new intervening mechanisms to maintain the same outcome. Sociologists argued that socioeconomic status (SES) is a fundamental cause of health ( 53 , 132 ), with Link and colleagues ( 74 , 100 ) providing considerable evidence in support of this perspective. In 1997, Williams argued that alongside SES and other upstream social factors, racism should be recognized as a fundamental cause of racial inequities in health ( 133 ). Evidence continues to accumulate highlighting racism as a driver of multiple upstream societal factors that perpetuate racial inequities in health for multiple non-dominant racial groups around the world ( 99 , 140 ).

Structural or Institutional Racism

We use the terms institutional and structural racism, interchangeably, consistent with much of the social science literature ( 13 , 55 , 106 ). Institutional racism refers to the processes of racism that are embedded in laws (local, state, and federal), policies, and practices of society and its institutions that provide advantages to racial groups deemed as superior, while differentially oppressing, disadvantaging, or otherwise neglecting racial groups viewed as inferior ( 13 , 104 ). We argue that the most important way through which racism affects health is through structural racism. We highlight evidence of the health impact of residential segregation but acknowledge that there are multiple other forms of institutional racism in society. For example, structural racism in the Criminal Justice System ( 84 , 130 , 142 ) can adversely affect health through multiple pathways ( 37 , 130 ).

Racial Residential Segregation

Racial residential segregation remains one of the most widely studied institutional mechanisms of racism and has been identified as a fundamental cause of racial health disparities due to the multiple pathways through which it operates to have pervasive negative consequences on health ( 7 , 38 , 60 , 136 ). Racial residential segregation refers to the occupancy of different neighborhood environments by race that was developed in the U.S. to ensure that whites resided in separate communities from blacks. Segregation was created by federal policies as well as explicit governmental support of private policies such as discriminatory zoning, mortgage discrimination, red-lining and restrictive covenants ( 107 ). This physical separation of races in distinctive residential areas (including the forced removal and relocation of American Indians) was shaped by multiple social institutions ( 83 , 136 ). Although segregation has been illegal since the Fair Housing Act of 1968, its basic structures established by the 1940s remain largely intact.

In the 2010 Census, residential segregation was at its lowest level in 100 years and the decline in segregation was observed in all of the nation’s largest metropolitan areas ( 43 ). However, the recent declines in segregation have been driven by a few blacks moving to formerly all-white residential areas with the declines in segregation having negligible impact on the very high percentage black census tracts, the residential isolation of most African-Americans, and the concentration of urban poverty ( 44 ). Although segregation is increasing for Hispanics, the segregation of African Americans remains distinctive. In the 2000 census middle class blacks were more segregated than poor Hispanics and Asians ( 81 ), and the segregation of immigrant groups has never been as high as the current segregation of African Americans ( 83 ).

Segregation and Health: Pathways

Segregation affects health in multiple ways ( 136 ). First, it is a critical determinant of SES, which is a strong predictor of variations in health. Research has found that segregation reduces economic status in adulthood by reducing access to quality elementary and high school education, preparation for higher education, and employment opportunities ( 136 ). Schools in segregated areas have lower levels of high-quality teachers, educational resources, per-student spending and higher levels of neighborhood violence, crime and poverty ( 91 ). Segregation also reduces access to employment opportunities by triggering the movement of low skill, high pay jobs from areas where racial minorities are concentrated to other areas and by enabling employers to discriminate against job applicants by using their place of residence as a predictor of whether or not the applicant would be a good employee ( 136 ) One national study found that the elimination of segregation would erase black-white differences in income, education and unemployment and reduce racial differences in single motherhood by two-thirds ( 28 ). Thus, segregation is responsible for the large and persistent racial/ethnic differences in SES. In 2016, for every dollar of income that white households received, Hispanics earned 73 cents and blacks earned 61 cents ( 110 ). And racial differences in health are stunningly larger. For every dollar of wealth that white households have, Hispanics have 7 pennies, and blacks have 6 pennies ( 120 ).

Segregation can also adversely affect health by creating communities of concentrated poverty with high levels of neighborhood disadvantage, low quality housing stock, and with both government and private sector demonstrating disinterest or divestment from these communities. In turn, the physical conditions (poor quality housing and neighborhood environments) and the social conditions (co-occurrence of social problems and disorders linked to concentrated poverty) that characterize segregated geographic areas lead to elevated exposure to physical and chemical hazards, increased prevalence and co-occurrence of chronic and acute psychosocial stressors, as well as, reduced access to a broad range of resources that enhance health ( 60 , 87 , 128 , 136 ). The living conditions created by concentrated poverty and segregation make it more difficult for residents of those contexts to practice healthy behaviors ( 7 , 60 , 128 , 136 ). Segregation also adversely affects the availability and affordability of care, contributing to lower access to high quality primary and specialty care and even pharmacy services ( 129 ).

Epidemiological Evidence Linking Segregation to Health

A 2011 review found nearly 50 empirical studies which generally found that segregation was associated with poorer health ( 128 ). A 2017 review and meta-analysis focused on 42 articles that examined the association between segregation and birth outcomes found that segregation was associated with increased risk of low birth rate weight and preterm birth for blacks ( 85 ). Other recent studies show that segregation is associated with increased risk of preterm birth for U.S.-born and foreign-born black women ( 79 ) and of stillbirth for blacks and whites, with the effects being more pronounced for blacks than for whites ( 131 ). A systematic review of 17 papers examining segregation and cancer, found that segregation was positively associated with later-stage diagnosis, elevated mortality and lower survival rates for both breast and lung cancers for blacks ( 65 ). Recent studies highlight variation in the association between segregation and health for population subgroups. One national study found that segregation was associated with poor self-rated health for blacks in high but not lower poverty neighborhoods ( 31 ). It was unrelated to poor health for whites but benefited whites indirectly by reducing the likelihood of their location in high poverty neighborhoods ( 31 ). And a 25 year longitudinal study found that cumulatively higher exposure to segregation was associated with elevated risk of incident obesity in black women but not black men ( 101 ).

Recommendations for Research on Institutional Racism

Several strategies should be implemented to further understanding of how institutional racism adversely affects health. First, there is a need to broaden our conceptualization and assessment of the multiple domains and contexts in which these structural processes are operative and empirically assess their impact on health. In a study of structural racism and myocardial infarction, Lukachko and colleagues ( 75 ) utilized four state-level measures of structural racism: political participation, employment, education and judicial treatment. The analyses revealed that state level racial disparities that disadvantaged blacks in political representation, employment and incarceration were associated with increased risk of MI in the prior year. Among whites, structural racism was unrelated to or had a beneficial effect on the risk of MI.

Second, immigration policy has been identified as a mechanism of structural racism ( 38 ) and systematic attention should be given to understanding how contemporary immigration policies adversely affect population health. Recent research suggests that anti-immigrant policies can trigger hostility toward immigrants leading to perceptions of vulnerability, threat, and psychological distress for both those who are directly targeted and those who are not ( 46 ). One study found that a large federal immigration raid was associated with an increase in low birthweight risk among infants born to Latina but not white mothers in that community a year after the raid ( 90 ). Immigration polices can also adversely affect health by leading to reduced utilization of preventive health services by both documented and undocumented immigrants ( 80 , 117 , 127 ).

Third, some of the methodological limitations of the current literature need to be addressed. Research on structural racism has been limited by the availability of data on structural levels and ecological analyses are limited in capturing the underlying processes. The available evidence suggests that the associations between segregation and health tend to vary based on the choice of a geographic unit of analysis ( 7 , 38 , 60 , 128 ). While smaller units tend to produce the most reliable estimates, the appropriate geographic level may not be consistent across all health outcomes. These analytic challenges are further exacerbated by difficulties disentangling the potential mediating and moderating effects that contribute to observed patterns. Many studies adjust for variables like poverty or other indicators of low SES and the social context which are likely a part of the pathway by which segregation exerts its effects ( 60 , 128 ). Future research needs to identify the proximal mechanisms linking segregation to health by using longitudinal data to establish temporality, and leveraging new statistical techniques ( 60 , 128 ). There is also a need for more complex system modeling approaches that seek to capture the impact of all of the dynamic historical processes that influence each other over time, at multiple levels of analysis ( 30 , 92 ).

Fourth, greater attention should be given to similarities and differences across national and cultural contexts. For example, segregation levels are rising in Europe and are positively associated with darker skinned nationalities and being Muslim but there has been little analysis of the effects of this segregation on SES and health ( 82 ). A study that compared a national sample of Caribbean blacks in the U.S. to those in the U.K. found that, in the U.S., increased black Caribbean ethnic density was associated with improved health while increased black ethnic density was associated with worse health but the opposite pattern was evident for Caribbean blacks in England ( 10 ). Comparative research could enhance our understanding of the contextual factors such as variation in the racialization of ethnic groups that could contribute to the observed associations.

Finally, we need a better understanding of the conditions under which group density can have positive versus adverse effects on health ( 86 ). A national study of Hispanics found that segregation was adversely related to poor self-rated health among US born Hispanics but it had a salutary effect on the health of the foreign-born ( 32 ). We need a clearer understanding of when and how segregation can give rise to health enhancing versus health damaging factors.

Cultural Racism

Cultural racism refers to the instillation of the ideology of inferiority in the values language, imagery, symbols and unstated assumptions of the larger society. It creates a larger ideological environment where the system of racism can flourish, and can undergird both institutional and individual level discrimination. It manifests itself through media, stereotyping and within institutions, and norms ( 49 , 140 ). It can yield inconspicuous forms of racism, such as implicit bias, as a result of the commonplace and continuous negative imagery about racial and ethnic minorities ( 140 ). Cultural forms of racism may serve as the conduit through which views regarding the limitations, stereotypes, values, images and ideologies associated with racial/ethnic minority groups are presented to society, and are consciously or subconsciously adopted and normalized ( 105 , 113 ).

The internalization of racism yields a tendency to focus on individual pathology and abilities rather than examining structural components that give rise to racial inequities. This internalization affects most members of the dominant group and a nontrivial proportion of the marginalized group as well, given that both groups are exposed to key socializing agents of the larger society that perpetuate racist beliefs ( 105 ). Research indicates that negative racial and ethnic stereotypes persist in entertainment, media, and fashion ( 18 , 140 ). A recent national survey of adults who work with children found that whites had high levels of negative racial stereotypes (lazy, unintelligent, violent and having unhealthy habits) towards non-whites, with the highest levels towards blacks followed by Native Americans and Hispanics ( 103 ).

Cultural Racism and Health

Cultural racism can affect health in multiple ways. First, cultural racism can drive societal policies that lead to the creation and maintenance of structures that provide differential access to opportunities ( 140 ). For example, a study of white residents revealed that their negative stereotypes about blacks influenced their housing decisions in ways that would maintain residential segregation ( 64 ). In this study whites rated an all-white neighborhood more positively (on the cost of housing, safety, future property value, and quality of schools) than an identical neighborhood if a black person were pictured in it.

Second, cultural racism can also lead to individual level unconscious bias that can lead to discrimination against outgroup members. In clinical encounters, these processes lead to minorities receiving inferior medical care compared to whites. Research indicates that across virtually every type of diagnostic and treatment interventions blacks and other minorities receive fewer procedures and poorer quality medical care than whites ( 112 ). Recent research documents the persistence of these patterns and reveals that higher implicit bias scores among physicians are associated with biased treatment recommendations in the care of black patients ( 123 ). Providers’ implicit bias is also associated with poorer quality of patient provider communication including provider nonverbal behavior ( 25 ).

Stereotype threat is a third pathway. This term refers to the anxieties and expectations that can be activated in stigmatized groups when negative stereotypes about their group are made salient. These anxieties can adversely affect academic performance and psychological functioning ( 114 ). Some limited evidence indicates that stereotype threat can lead to increased anxiety, reduced self-regulation and impaired decision-making that can lead to unhealthy behaviors, poor patient-provider communication, lower levels of adherence to medical advice, increased blood pressure and weight gain among stigmatized groups ( 6 , 114 , 141 ). Relatedly, a study documented that exposure of American Indian students to Native American mascots, leads to declines in self-esteem, community worth and achievement aspirations ( 35 ). Fourth, as noted, some members of stigmatized racial populations respond to the pervasive negative racial stereotypes in the culture by accepting them to be true. This endorsement of the dominant society’s beliefs about their inferiority is called internalized racism or self-stereotyping. Research indicates that it is associated with lower psychological well-being and higher levels of alcohol consumption, depressive symptoms and obesity ( 139 ).

Recommendations for Research on Cultural Racism

Future research should aim to understand how and why cultural racism, when it is measured as elevated levels of racial prejudice at the community level, is associated with poorer health for racial minorities, and sometimes all persons, who live in that community. Recent studies have found that residing in communities with high levels of racial prejudice is positively associated with overall mortality ( 20 , 67 ), heart disease mortality ( 68 ), and low birthweight ( 21 ). Community-level prejudice against immigrants has also been associated with increased mortality among US-born immigrant adults ( 89 ). However, these studies are ecological in nature and lack adjustment for individual-level factors

Second, we need to better understand how internalized racism can affect health. There is limited understanding of the conditions under which internalized racism has adverse consequences for health, the groups that are most vulnerable, and the range of health and health-related outcomes that may be affected ( 140 ). The optimal measurement of internalized racism is also a challenge. Studies have used scales of internalized racism, minority group endorsement of negative stereotypes and African Americans’ scores on anti-black bias on the IAT. It is currently unclear how these measures correlate with each other and the extent to which they may capture different aspects of internalized racism. Beyond the individual, future work should also examine internalized racism in a more collective form that could facilitate understanding of the cultural and structural pervasiveness of racism at the societal level racial ( 105 ). Research should also assess if and how racist ideologies and oppression become internalized among immigrants in the United States and how these are associated with health outcomes.

Discrimination

Discrimination is the most frequently studied domain of racism in the health literature. It exists in two forms: 1) where individuals and larger institutions, deliberately or without intent, treat racial groups differently, resulting in inequitable access to opportunities and resources (e.g., employment, education, and medical care) by race/ethnicity, and 2) self-reported discrimination, a sub-set of these experiences that individuals are aware of. These latter incidents are a type of stressful life experience that can adversely affects health, similar to other kinds of psychosocial stressors. Considerable scientific evidence, supports of the first pathway, much of it captured through audit studies (those in which researchers use individuals who are equally qualified in every respect but differ only in race or ethnicity) that document the persistence of discrimination in many contexts including employment, education, housing, credit, and criminal justice systems ( 93 ). This discrimination in social institutions contributes to the differential access to resources and opportunities and results in SES and other material disadvantages.

A large proportion of the discrimination literature focuses on the second pathway with the evidence indicating that stigmatized racial and ethnic populations and other socially marginalized groups around the world report experiences of discrimination that are inversely related to good health ( 109 , 139 , 140 ). Researchers refer to these experiences as self-reported discrimination, perceived discrimination, and racial discrimination, and we use these terms interchangeably. Self-reports of discrimination can adversely affect health through triggering negative emotional reactions that can lead to altered physiological reactions and changes in health behaviors, that can increase the risk of poor health ( 41 ). We highlight key patterns and trends in this research on discrimination and health.

A 2015 meta-analysis assessed the scientific evidence for the association between self-reported racial discrimination and health from over 300 articles published between 1983 and 2013 ( 95 ). Eighty one percent of studies were from the U.S. followed by the U.K., Australia, Canada, the Netherlands and 15 other countries. The analyses found that the association between discrimination and mental health was stronger than for physical health. This was inconsistent with a prior review that found similar effect sizes for physical and mental health ( 96 ). Interestingly, ethnicity moderated the effect of self-reported racial discrimination on health with the association between perceived racial discrimination and mental health being stronger for Asian Americans and Latino Americans compared to blacks and the association with physical health being stronger for Latinos than for blacks.

While the review by Paradies and colleagues ( 95 ) is the most comprehensive one published to date, it excluded many studies that are included in other reviews. Because of its focus on experiences of “racism”, it excluded studies using measures of discrimination, bias and unfair treatment where race or ethnicity were not explicitly noted as the reason for discrimination. This included many studies using the Everyday Discrimination Scale and the Major Experiences of Discrimination Scale ( 137 , 143 ) which use a two-stage approach where respondents are first asked about generic experiences of bias and then a follow-up question ascertains the main reason. Many studies that have used these measures have not asked or analyzed the follow-up question. Relatedly, studies were also excluded that used a version of these two instruments that were utilized in the national MIDUS study ( 59 ). It explicitly asked respondents to report only instances where they had been “discriminated against” because of their race or other specific social characteristics ( 59 ). It appears that the use of “discrimination” does not affect the reports of bias by blacks but depresses reports by whites ( 8 ). Importantly, multiple reviews have concluded that the deleterious health effects of discrimination are generally evident with the generic perception of bias or unfair treatment irrespective of which social status category the experience is attributed to ( 70 , 96 , 139 ).

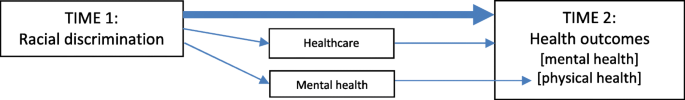

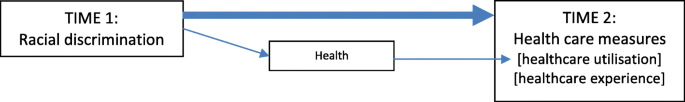

Several recent reviews provide additional evidence of the pervasive negative health effects of exposure to discrimination. A 2015 review indicated that self-reported discrimination is related not only to indicators of mental health symptoms and distress but also to defined psychiatric disorders ( 70 ). Moreover, there is growing evidence that self-reported discrimination is associated with preclinical indicators of disease, including increased allostatic load, inflammation, shorter telomere length, coronary artery calcification, dysregulation in cortisol and greater oxidative stress ( 70 ). Linkages between self-reported racial discrimination and physical health outcomes have been documented in multiple recent reviews with research indicating positive associations between reports of discrimination and adverse cardiovascular outcomes ( 72 ), BMI and incidence of obesity ( 12 ), hypertension and nighttime ambulatory blood pressure ( 33 ), engaging in high-risk behaviors ( 40 ), alcohol use and misuse ( 42 ), and poorer sleep ( 111 ). Research also indicates that experiences of discrimination can shape healthcare seeking behaviors and adherence to medical regiments. A 2017 review and meta-analysis of studies on discrimination and health service utilization revealed that perceived discrimination was inversely related to positive experiences with regards to healthcare (e.g., satisfaction with care or perceived quality of care) and reduced adherence to medical regimens and delaying or not seeking healthcare ( 11 ).

Research on stress and health reveals that in addition to stressful experiences affecting health through actual exposure, the threat of exposure as captured by responses of vigilance, worry, rumination and anticipatory stress can prolong the negative effect of stressors and exacerbate the negative effects of stressful experiences on health ( 17 ). Increased attention has been given to capturing vigilance with regards to the threat of discrimination. Several recent studies have used the Heightened Vigilance scale ( 23 ) or a shortened version of it and have found that vigilance about discrimination was positively associated with depressive symptoms ( 66 ), sleep difficulties ( 50 ), and hypertension ( 52 ) and contributed to racial differences for these outcomes. Another recent study with the same measure also found that heightened vigilance was associated with increased waist circumference and BMI among black but not white women ( 51 ). However, these studies have all been cross-sectional and future research using longitudinal study designs would strengthen the evidence for vigilance as a risk factor for health.

Another trend in recent research on discrimination and health is increasing attention to its negative effects on the health and wellbeing of children and adolescents. A 2013 review of discrimination and the health of persons age zero to 18 years old found 121 studies that had examined this association ( 102 ). There were consistent positive associations between self-reported discrimination and indicators of mental health problems, negative health behaviors and physical health outcomes. There is also accumulating evidence that the adverse health effects of discrimination in childhood and adolescence are evident early in life and are a likely contributor to racial inequities in health in young adulthood. For example, a study of black adolescents found that those who reported high levels of discrimination at age 16, 17, and 18 had elevated levels of stress hormones (cortisol, epinephrine and norepinephrine), blood pressure, inflammation and BMI by age 20 ( 16 ).

Research has documented cumulative effects of discrimination on health with greater negative impact evident with increasing levels of exposure to the stress of discrimination. A longitudinal study of ethnic minorities in the United Kingdom identified a dose-response relationship between the accumulation of experiences of discrimination with the deterioration in mental health, with the greatest degree of mental health deterioration evident among those who reported two or more experiences of discrimination at both time points ( 125 ).

Recommendations for Research on Discrimination and Health

As noted, audit studies and other field experiments document the existence of discrimination in many societal institutions and contexts. More concerted efforts are needed to apply knowledge and insights from these studies on the structuring and persistence of discrimination within institutional settings to understand how such discrimination sustains racial disadvantage in ways that shape health outcomes and impact racial health inequities. More generally, despite the burgeoning literature on self-reported discrimination and health, there are some fundamental questions that remain unanswered, including the conditions under which particular aspects of discrimination are related to changes in health status for specific indicators of health status. Such analyses might shed light on findings where the pattern is not uniform. For example, cohort studies have found a positive association ( 9 ), no association ( 2 ) and an inverse association between discrimination and all-cause mortality ( 34 ). The contribution of differences in the assessment of discrimination and in the populations covered to the observed patterns is not well understood.

Prior reviews indicate that the literature on self-reported discrimination and health has been plagued with multiple measurement challenges that probably lead to an underestimation of the actual effects of discrimination on health ( 62 , 135 ). These challenges include identifying the optimal approaches for accurately and comprehensively measuring discrimination and ensuring adequate assessment of key stressful components of discriminatory experiences such as their chronicity, recurrence, severity and duration and distinguishing incidents that are traumatic from those that are not. These challenges remain urgent issues to address in future research.

A limitation of most prior research on discrimination and health is the focus on singular identities of the study participants. Emerging evidence suggests that utilizing an intersectionality framework that examines associations between discrimination and health, with the simultaneous consideration of multiple social categories (e.g., race, sex, gender, SES), leads to larger associations than when only a single social category is considered ( 71 ). Experiences of discrimination should also be considered both for an individual’s self-identified race, as well as for one’s socially assigned race ( 124 ). Recent studies also provide striking evidence of the persistence of discrimination based on skin color within multiple Latino ethicities ( 97 ) and for blacks ( 88 ) suggesting that skin color should be an essential domain of assessing discrimination in future research.

An enhanced understanding of how discrimination combines with other stressors to shape health and racial/ethnic inequities in health is also needed. Self-reported experiences of discrimination do not fully encompass psychosocial stressors linked to non-dominant racial/ethnic status nor the full contribution of racism-related stressors. A study that measured multiple dimensions of discrimination (everyday, major experiences and work discrimination) along with brief measures of childhood adversity, lifetime traumas, recent life events and chronic stressors in the domains of work, finances, relationships and neighborhood, found a graded association between the number of stressors and multiple indicators of morbidity, with each additional stressor associated with worse health ( 115 ). Moreover, stress exposure explained a substantial portion of the residual effect of race/ethnicity after adjustment had been made for SES. Fully capturing stressful exposures for vulnerable populations should also include the assessment of stressors linked to the physical, chemical, and built environment ( 139 ).

Attention should also be given to understanding the contribution of stressors that, at face value, are not linked to racism but that reflect the effects of racism on health. Research on community bereavement shows that structural conditions linked to racism lead to lower life expectancy for blacks compared to whites ( 122 ). As a result, compared to whites, black children are three times as likely to lose a mother by age 10, and black adults are more than twice as likely to lose a child by age 30, and a spouse by age 60. This elevated rate of bereavement and loss of social ties is a stressor that adversely affects levels of social ties and physical and mental health of blacks across the life course ( 119 ). The death of loved ones is included on standard assessments of life events, but its links to racism typically recognized.

Another priority for future research is to better identify the conditions under which vicarious experiences of discrimination can affect health, The term, vicarious discrimination, refers to discriminatory experiences that were not directly experienced by an individual but were faced by others in their network or with whom they identify ( 47 ). A recent systematic review of 30, mainly longitudinal, studies found that that indirect, secondhand exposure to racism was adversely related to child health ( 47 ). The range of contexts in which vicarious discrimination occurs is broad. Recent studies suggest that online discrimination through social media and frequent reports and visualization of incidents of police violence directed towards black, Latino, and Native American communities may also have negative health consequences ( 121 ). A recent, nationally-representative, quasi-experimental study found that each police killing of an unarmed black male Americans worsened mental health among blacks in the general population ( 14 ).

Increased hostility and resentment towards racial and ethnic minority groups and immigrants in the U.S. as well as political polarization associated with the recent presidential election and its aftermath also deserve more research attention ( 138 ). A recent longitudinal study of high school juniors interviewed before and after the presidential election found that many reported concern, worry or stress regarding the increasing hostility and discrimination of people because of their race, immigrant status, religion, or other social factors. A year later, higher concern about discrimination was associated with increases in cigarette smoking, alcohol use, substance use, and greater odds of depression and ADHD ( 69 ).

Future research also needs to better document the role of discrimination, and other dimensions of racism, in accounting for racial disparities in health. Studies from Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the U.S. have found that self-reports of discrimination make an incremental contribution over and above income and education in accounting for racial/ethnic inequities in health ( 139 ). However, most studies of discrimination neglect to empirically quantify the contribution of discrimination to the patterns and trends of inequities in health.

Interventions

Future research on racism and health needs to give more sustained attention to identifying interventions to reduce and prevent racism, as well as, to ameliorate its adverse health effects. Research on interventions to address the multiple dimensions of racism is still in its infancy ( 94 , 141 ).

Addressing Institutional Racism

Reskin ( 106 ) emphasizes that because racism is a system that consists of a set of dynamically related components or subsystems, disparities in any given domain is a result of processes of reciprocal causality across multiple subsystems. Accordingly, interventions should address the interrelated mechanisms and critical leverage points through which racism operates, and explicitly design multi-level interventions to get at the multiple processes of racism simultaneously. The systemic nature of racism implies that effective solutions to addressing racism need to be comprehensive and emphasize upstream/structural/institutional interventions ( 142 ). The civil rights policies of the 1960s are prime examples of race-targeted policies that that improved socioeconomic opportunities and living conditions, narrowed the black-white economic gap between the mid 1960s and the late 1970s and reduced health inequities ( 3 , 4 , 26 , 45 , 58 ). Interventions to improve household income, education and employment opportunities, and housing and neighborhood conditions have also demonstrated health benefits ( 141 ).

Additional income to households with modest economic resources suggests that added financial resources are associated with improved health ( 141 ). The Great Smoky Mountains Study was a natural experiment that assessed the impact of extra income received by American Indian households due to the opening of a Casino, on the health of Native youth ( 27 ). The study found declining rates of deviant and aggressive behavior among adolescents whose families received additional income; and increases in formal education and declines in the incidence of minor criminal offenses in young adulthood, and the elimination of Native American-white disparities on both of these outcomes ( 1 ). The Abecedarian project that randomized economically disadvantaged children, birth to 5 years of age, most of them Black, to an early childhood nurturing program also illustrates that interventions efforts at an early age can be beneficial ( 19 ). By their mid 30s, the intervention group had lower levels of multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease than the controls. Community initiatives and efforts to build community capacity around racism may also have the potential to improve health ( 140 , 141 ). One study demonstrated that cultural empowerment among Native communities, in the form of civil and governmental sovereignty and the presence of a building for cultural activities, had a strong inverse relationship with youth suicide ( 22 ).

Addressing Cultural Racism

Most interventions aimed at reducing cultural racism focus on addressing implicit biases or enhancing cultural competence. A recent review found that cultural competency interventions can lead to improvements in provider knowledge, skills and attitudes regarding cultural competency and health care access and utilization, but there is little evidence that these interventions affect health outcomes and health equity ( 118 ). While extensive evidence documents that healthcare students and professionals have an anti-black there are no effective interventions to reduce this bias among providers ( 76 ). However, Devine and colleagues documented that a comprehensive program that deployed multiple strategies to reduce implicit biases found a sustained reduction in implicit biases in nonblack undergraduate students three months after the program began ( 29 ). Future research needs to assess the generalizability of the effects of this intervention to other groups.

Interventions, targeted at individuals, that seek to neutralize cultural racism have shown positive socioeconomic and health benefits. Values affirmation interventions (in which youth enhance their sense of self-worth by reflecting on and writing about their most important value) and social belonging interventions (which create a sense of relatedness) have been shown to markedly improve academic performance and health of stigmatized racial groups ( 24 ). There is an emerging body of evidence that suggests that similar self-affirmation strategies can enhance an individual’s capacity to cope with stressful situations and lead to improved health behaviors ( 24 ).

Addressing Discrimination

Effective strategies can be deployed to reduce discrimination against individuals that occur within institutional contexts. For example, in the employment domain, research reveals that discrimination can be reduced and the proportion of under-represented groups markedly increased through organizational policy changes that require mandatory programs, or programs with explicit authority and accountability that are supported by organizational leadership and rigorously monitored ( 57 ). Discrimination can also be minimized in employment decisions by having applications reviewed with the names of the applicants removed from the application package ( 61 ). Many interventions targeting interpersonal discrimination focus on reductions in prejudice and stereotyping through increased interracial contact. However, evidence in support of the contact theory of prejudice indicates that reductions in prejudice and discrimination are observed only when groups meet specific conditions: they are equivalent in status, have shared goals, cooperate to achieve shared goals, and have the support of authority figures ( 98 ).

Research on interpersonal discrimination also suggests that coping strategies and resources (such as social ties, religious involvement and optimism) can mitigate at least some of the detrimental effects of racial discrimination on health ( 70 ). Racial identity is another promising strategy but studies have found both protective and exacerbating effects of identity ( 144 ). At the present time, we do not clearly understand the determinants of discrepant findings and the conditions under which specific aspects of identity have positive or negative effects for particular indicators of health for specific population subgroups.

Needed Research On Interventions

Although there is emerging evidence that a broad range of strategies may reduce certain aspects of racism and enhance racial equity, there is still a lot that we do not understand. For example, interventions that have improved neighborhood and housing conditions have been implemented on a small scale and they have yet to seriously address either residential racial segregation or the concentration of poverty in the metropolitan areas in which they have been implemented. Residential segregation has been identified as a leverage point or fundamental causal mechanism by which institutional racism creates and sustains racial economic inequities ( 106 , 136 ). Thus, dismantling the core institutional mechanisms of segregation will require scaling up interventions that address its key underlying mechanisms. Relatedly, we lack the empirical evidence to identify which mechanisms of segregation (e.g., educational opportunity, labor market, housing quality) should be tackled first, would have the largest impact, and is most likely to trigger ripple effects to other pathways.

Research also needs to identify if and when observed health effects of reducing racism would be larger if comprehensive, multi-level intervention strategies (instead of interventions targeted at a single level) were deployed to neutralize the negative impact of the pathogenic effects of racism. For example, we are unaware whether we would observe larger positive effects if interventions focused on upstream interventions (e.g., in housing, education and additional income) were combined with an individual-level targeted strategy such as a self-affirmation intervention ( 24 ). Relatedly, interventions need to be evaluated for the extent to which they may be differentially effective across various subgroups of the population. The cost-effectiveness of interventions also needs to be assessed for population subgroups.

Taking the systemic nature of racism seriously also highlights that it is deeply embedded in other political, economic and cultural structures of society and that many powerful societal actors are likely to be resistant to change because they currently benefit from the status quo. Research to advance an agenda to dismantle racism and its negative effects must invest in studies that delineate how to overcome societal inertia, increase empathy for stigmatized racial/ethnic populations, build political will and identify optimal communication strategies to raise public and stakeholder awareness of the societal benefits of racial equity agenda ( 142 ).

Cross-Cutting Issues

Much of the research described in this review has focused on a single mechanism of racism (structural/institutional, cultural, discrimination) through which racism may influence health. Differentiating between these mechanisms allows researchers to clarify potential pathways, measure outcomes, and explore interventions. However, the impact of addressing a single dimension of racism will be diminished by the system of racial oppression which interacts across sectors and domains of racism. Tying together interconnected data on health and racism will be critical for health disparities researchers moving forward. Some emerging topics lend themselves to this multi-dimensional, cross-cutting research—allowing investigators to better understand and address the systemic nature of racism. Priority topics include studying the effects of racism throughout the life course, understanding the potential intergenerational effects of racism, and the impact of racism on white people.

Understanding Racism across the Life Course

Life course research aims to examine how early exposures, such as lead poisoning in utero, or adversity in early childhood, can impact health in adulthood. This perspective can incorporate early context, sensitivity and latency periods, the accumulation of risk over time, and etiologic origins of disease ( 39 ). When examining racism as an exposure, understanding how individuals encounter racism across the life course is one example of a cross-cutting issue in need of more research ( 38 , 39 , 128 ). A life course approach can begin to unpack how exposures to interpersonal, cultural, and structural racism may evolve and relate to each other across developmental stages, as individuals interact with their neighborhoods and educational systems, and health care systems ( 106 ). A recent study, for example, documented a relationship between early childhood lead exposure and adult incarceration ( 108 ). It is likely that multiple mechanisms of racism could have combined, additively and interactively over time, to undergird this association ( 78 ). Life course approaches are also important for determining how and when it is most opportune to intervene on racism. The Great Smoky Mountains Study found that providing additional income to Native American households led to a reduction in adolescent risk behaviors, but only among those who were the youngest when the income supplements began, and who thus had the longest period of exposure ( 27 ). A life course approach can identify key periods of increased risk as well as opportunities for intervention and resilience.

Intergenerational Transmission of Racism’s Effects

An extension of the life course perspective is a focus on the impact of intergenerational transmission of the effects of racism, from parent to offspring. Though still in its infancy, research on the intergenerational transmission of racism could enhance and clarify observational research which posits that descendants of survivors of mass and targeted trauma experience grief and other mental, behavioral, and somatic symptoms akin to what would might be expected if the trauma was witnessed directly ( 48 ). Long-term adverse health impacts linked to Jim Crow laws illustrate the long reach of institutional racism ( 63 ). Studies of children of Holocaust survivors and multiple generations of Native Americans suggest a link between these racialized traumatic experiences and the well-being of future generations ( 119 ). Possible pathways include the effects of parenting and community norms, the transfer of resources (i.e. wealth, land), and potentially, heritable and non-heritable epigenetic changes caused by external stressors ( 126 ). Differential DNA methylation is one type of epigenetic difference that has been found among adult children of holocaust survivors, which may affect gene expression at the methylated loci ( 119 ). Concerted new research efforts are needed to provide a more nuanced understanding of how racialized experiences are embodied for future generations.

Racism and the Health of Whites

There is growing scientific interest in how the system of racism can have both positive and negative effects on the health of whites ( 77 ). Whites as a whole have better health than the historically oppressed groups in the U.S., but they are less healthy than whites in other advanced economies. Inadequate attention has been given to delineating the ways in which racism could simultaneously advantage whites compared to other racial groups in the U.S. while creating conditions that are inimical to the health of all groups, including disadvantaging large segments of the white population, and imposing ceilings that prevent many middle class whites from attaining a level of good health seen elsewhere ( 77 ). For example, racial animus towards blacks has led to white opposition to a broad range of social programs, including the Affordable Care Act, which would benefit a large proportion of whites ( 116 ). In addition, while research on internalized racism has heavily focused on its potential negative health effects on members of racial and ethnic minority groups, whites also have high levels of internalized racism (that is, internalized racial superiority) that could affect how whites respond to economic adversity perhaps contribute to increasing rates of “deaths of despair” among low SES whites ( 77 , 105 ). Research on self-reported discrimination and hqealth has also observed negative effects of such experiences among whites ( 70 ). It is not clear that all whites are equally vulnerable. One study found that discrimination adversely affected only whites who were male and who belonged to ethnic subgroups with a history of discrimination (Polish, Irish, Italian or Jewish) ( 54 ). Another study found that discrimination based on class helped to explain SES differences in allostatic load in a sample of white adolescents ( 36 ). Concerted attention should be given to the myriad ways in which various aspects of racism can have positive and negative effects on the health of whites and particular subgroups of whites.

Conclusions

The study of contemporary racism and its impact on health is complex, as manifestations of structural, cultural, and interpersonal racism adapt to changes in technology, cultural norms, and political events. This body of research illustrates the myriad ways in which the larger social environment can get under the skin to drive health and inequities in health. While there is much that we yet need to learn, the quality and quantity of research continues to increase in this area and there is an acute need for increased attention to identifying the optimal interventions to reduce and eliminate the negative effects of racism on health. Understanding and effectively addressing the ways in which racism affects health is critical to improving population health and to making progress in reducing large and often intractable racial inequities in health.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this paper was supported by grant U19 AG 051426 from the National Institute of Aging. We wish to thank Sandra Krumholz for her assistance with preparing the manuscript.

Literature Cited

- 1. Akee RKQ, Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ. 2010. Parents’ Incomes and Children’s Outcomes: A Quasi-experiment Using Transfer Payments from Casino Profits. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2: 86–115 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Albert MA, Cozier Y, Ridker PM, Palmer JR, Glynn RJ, et al. 2010. Perceptions of Race/Ethnic Discrimination in Relation to Mortality Among Black Women: Results From the Black Women’s Health Study. Archives of internal medicine 170: 896–904 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Almond D, Chay KY. 2006. The Long-Run and Intergenerational Impact of Poor Infant Health: Evidence from Cohorts Born During the Civil Rights Era manuscript, UC Berkeley Department of Economics. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Almond D, Chay KY, Greenstone M. 2006. Civil Rights, the War on Poverty, and Black-White Convergence in Infant Mortality in the Rural South and Mississippi, MIT Dept of Economics Working Paper Series [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Arias E, Xu J, Jim MA. 2014. Period life tables for the non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native population, 2007–2009. Am J Public Health 104 Suppl 3: S312–9 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Aronson J, Burgess D, Phelan SM, Juarez L. 2013. Unhealthy interactions: The role of stereotype threat in health disparities. American journal of public health 103: 50–56 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. 2017. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. The Lancet 389: 1453–63 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Barkan SE. 2018. Measuring Perceived Mistreatment: Potential Problems in Asking About “Discrimination”. Sociological Inquiry 88: 245–53 [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Barnes LL, Mendes de Leon CF, Lewis TT, Bienias JL, Wilson RS, Evans DA. 2008. Perceived Discrimination and Mortality in a Population-based Study of Older Adults. American journal of public health 98: 1241–47 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Becares L, Nazroo J, Jackson J, Heuvelman H. 2012. Ethnic density effects on health and experienced racism among Caribbean people in the US and England: a cross-national comparison. Soc Sci Med 75: 2107–15 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Ben J, Cormack D, Harris R, Paradies Y. 2017. Racism and health service utilisation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one 12: e0189900. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Bernardo CdO, Bastos JL, González‐Chica DA, Peres MA, Paradies YC 2017. Interpersonal discrimination and markers of adiposity in longitudinal studies: a systematic review. Obesity Reviews 18: 1040–49 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Bonilla-Silva E 1997. Rethinking racism: Toward a structural interpretation. American sociological review: 465–80

- 14. Bor J, Venkataramani AS, Williams DR, Tsai AC. 2018. Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: a population-based, quasi-experimental study. In Lancet doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31130-9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- 15. Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. 2010. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. American journal of public health 100: S186–S96 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Brody GH, Lei MK, Chae DH, Yu T, Kogan SM, Beach SRH. 2014. Perceived discrimination among African American adolescents and allostatic load: a longitudinal analysis with buffering effects. Child Dev 85: 989–1002 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Brosschot JF, Gerin W, Thayer JF. 2006. The perservative cognition hypothesis: A review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation, and health. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 60: 113–24 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Burkley M, Burkley E, Andrade A, Bell AC. 2017. Symbols of pride or prejudice? Examining the impact of Native American sports mascots on stereotype application. The Journal of social psychology 157: 223–35 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Campbell FA, Conti G, Heckman JJ, Moon SH, Pinto R, et al. 2014. Early childhood investments substantially boost adult health. Science 343: 1478–85 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Chae DH, Clouston S, Hatzenbuehler ML, Kramer MR, Cooper HLF, et al. 2015. Association between an internet-based measure of area racism and black mortality. PLoS ONE 10 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Chae DH, Clouston S, Martz CD, Hatzenbuehler ML, Cooper HLF, et al. 2018. Area racism and birth outcomes among Blacks in the United States. Social Science & Medicine 199: 49–55 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Chandler MJ, Lalonde C. 1998. Cultural Continuity as a Hedge against Suicide in Canada’s First Nations. Transcultural Psychiatry 35: 191–219 [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Clark R, Benkert RA, Flack JM. 2006. Large arterial elasticity varies as a function of gender and racism-related vigilance in black youth. Journal of Adolescent Health 39: 562–69 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Cohen GL, Sherman DK. 2014. The Psychology of Change: Self-Affirmation and Social Psychological Intervention. Annual Review of Psychology 65: 222–71 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, Beach MC, Sabin JA, et al. 2012. The Associations of Clinicians’ Implicit Attitudes About Race With Medical Visit Communication and Patient Ratings of Interpersonal Care. American Journal of Public Health 102: 979–87 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Cooper RS, Steinhauer M, Schatzkin A, Miller W. 1981. Improved mortality among U.S. blacks, 1968–1978: The role of antiracist struggle. International Journal of Health Services 11: 511–22 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Copeland W, Angold A. 2010. Association of Family Income Supplements in Adolescence With Development of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders in Adulthood Among an American Indian Population. The Journal of the American Medical Association 303: 1954–60 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Cutler DM, Glaeser EL. 1997. Are ghettos good or bad? The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112: 827–72 [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Devine PG, Forscher PS, Austin AJ, Cox WTL. 2012. Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. Journal of experimental social psychology 48: 1267–78 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Diez Roux AV. 2011. Complex systems thinking and current impasses in health disparities research. Am J Public Health 101: 1627–34 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Do DP, Frank R, Iceland J. 2017. Black-white metropolitan segregation and self-rated health: Investigating the role of neighborhood poverty. Social Science & Medicine 187: 85–92 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Do DP, Frank R, Zheng C, Iceland J. 2017. Hispanic Segregation and Poor Health: It’s Not Just Black and White. American journal of epidemiology 186: 990–99 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Dolezsar CM, McGrath JJ, Herzig AJM, Miller SB. 2014. Perceived racial discrimination and hypertension: A comprehensive systematic review. Health Psychology 33: 20–34 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Dunlay SM, Lippmann SJ, Greiner MA, O’Brien EC, Chamberlain AM, et al. 2017. Perceived Discrimination and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Older African Americans: Insights from the Jackson Heart Study. Mayo Clinic proceedings 92: 699–709 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Fryberg SA, Markus HR, Oyserman D, Stone JM. 2008. Of warrior chiefs and Indian princesses: The psychological consequences of American Indian mascots. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 30: 208–18 [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Fuller-Rowell TE, Evans GW, Ong AD. 2012. Poverty and Health: The Mediating Role of Perceived Discrimination. Psychological Science 23: 734–39 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Gebremariam M, Nianogo R, Arah O. 2018. Weight gain during incarceration: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews 19: 98–110 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Gee GC, Ford CL. 2011. Structural racism and health inequities: old issues, new directions. Du Bois review: social science research on race 8: 115–32 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Gee GC, Walsemann KM, Brondolo E. 2012. A life course perspective on how racism may be related to health inequities. American Journal of Public Health 102: 967–74 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Gibbons FX, Stock ML. 2017. Perceived Racial Discrimination and Health Behavior: Mediation and Moderation. In The Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health, ed. Major B, Dovidio JF, Link BG, pp. 355–77. New York: Oxford University Press [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Gibbons FX, Stock ML. 2017. Perceived Racial Discrimination and Health Behavior: Mediation and Moderation: Oxford University Press [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Gilbert PA, Zemore SE. 2016. Discrimination and drinking: A systematic review of the evidence. Social Science & Medicine 161: 178–94 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Glaeser E, Vigdor J. 2012. The end of the segregated century: Racial separation in America’s neighborhoods, 1890–2010. Rep. 66, Manhattan Institute for Policy Research New York [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Glaeser EL, Vigdor JL. 2001. Racial segregation in the 2000 Census: Promising news, The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Hahn R, Truman B, Williams D. 2018. Civil rights as determinants of public health and racial and ethnic health equity: Health care, education, employment, and housing in the United States. SSM-population health 4: 17–24 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Hatzenbuehler ML, Prins SJ, Flake M, Philbin M, Frazer MS, et al. 2017. Immigration policies and mental health morbidity among Latinos: A state-level analysis. Soc Sci Med 174: 169–78 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Heard-Garris NJ, Cale M, Camaj L, Hamati MC, Dominguez TP. 2018. Transmitting Trauma: A systematic review of vicarious racism and child health. Social Science & Medicine 199: 230–40 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Heart MYHB, DeBruyn LM. 1998. The American Indian holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief. American Indian and Alaska native mental health research 8: 56. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Hicken MT, Kravitz-Wirtz N, Durkee M, Jackson JS. 2018. Racial inequalities in health: Framing future research. Soc Sci Med 199: 11–18 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Hicken MT, Lee H, Ailshire J, Burgard SA, Williams DR. 2013. “Every shut eye, ain’t sleep”: The role of racism-related vigilance in racial/ethnic disparities in sleep difficulty. Race and social problems 5: 100–12 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Hicken MT, Lee H, Hing AK. 2018. The weight of racism: Vigilance and racial inequalities in weight-related measures. Social science & medicine 199: 157–66 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Hicken MT, Lee H, Morenoff J, House JS, Williams DR. 2014. Racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension prevalence: reconsidering the role of chronic stress. American journal of public health 104: 117–23 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. House JS, Kessler RC, Herzog AR, Mero R, Kinney A, Breslow M. 1990. Age, socioeconomic status, and health. Milbank Quarterly 68: 383–411 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Hunte HE, Williams DR. 2009. The association between perceived discrimination and obesity in a population-based multiracial and multiethnic adult sample. Am J Public Health 99: 1285–92 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Jones JM. 1997. Prejudice and racism 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Kaestner R, Pearson JA, Keene D, Geronimus AT. 2009. Stress, Allostatic Load, and Health of Mexican Immigrants. Social Science Quarterly 90: 1089–111 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Kalev A, Dobbin F, Kelly E. 2006. Best practices or best guesses? Assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity policies. American sociological review 71: 589–617 [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Kaplan GA, Ranjit N, Burgard S. 2008. Lifting Gates--Lengthening Lives: Did Civil Rights Policies Improve the Health of African-American Woman in the 1960s and 1970s? In Making Americans Healthier: Social and Economic Policy as Health Policy, ed. Schoeni RF, House JS, Kaplan GA, Pollack H, pp. 145–69. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Publications [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. 1999. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of health and social behavior 40: 208–30 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Kramer MR, Hogue CR. 2009. Is segregation bad for your health? Epidemiologic reviews 31: 178–94 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 61. Krause A, Rinne U, Zimmermann KF. 2012. Anonymous job applications in Europe. IZA Journal of European Labor Studies 1: 5 [ Google Scholar ]

- 62. Krieger N 2014. Discrimination and health inequities. Int J Health Serv 44: 643–710 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 63. Krieger N, Chen JT, Coull BA, Beckfield J, Kiang MV, Waterman PD. 2014. Jim Crow and premature mortality among the US black and white population, 1960–2009: an age–period–cohort analysis. Epidemiology (Cambridge, MA) 25: 494–504 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 64. Krysan M, Farley R, Couper MP. 2008. In the eye of the beholder: Racial beliefs and residential segregation. Du Bois Review 5: 5–26 [ Google Scholar ]

- 65. Landrine H, Corral I, Lee JG, Efird JT, Hall MB, Bess JJ. 2017. Residential Segregation and Racial Cancer Disparities: A Systematic Review. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities 4: 1195–205 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 66. LaVeist TA, Thorpe RJ Jr., Pierre G, Mance GA, Williams DR 2014. The Relationships among Vigilant Coping Style, Race, and Depression. Journal of Social Issues 70: 241–55 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 67. Lee H, Wildeman C, Wang EA, Matusko N, Jackson JS. 2014. A heavy burden: the cardiovascular health consequences of having a family member incarcerated. Am J Public Health 104: 421–7 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 68. Leitner JB, Hehman E, Ayduk O, Mendoza-Denton R. 2016. Blacks’ Death Rate Due to Circulatory Diseases Is Positively Related to Whites’ Explicit Racial Bias. Psychol Sci 27: 1299–311 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 69. Leventhal AM Cho J Andrabi N Barrington-Trimis J 2018. Association of Reported Concern Over Increasing Societal Discrimination and Adverse Behavioral Health Outcomes in Late Adolescence, 2016–2017. JAMA Pediatrics, In Press [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- 70. Lewis TT, Cogburn CD, Williams DR. 2015. Self-Reported Experiences of Discrimination and Health: Scientific Advances, Ongoing Controversies, and Emerging Issues. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 11: 407–40 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 71. Lewis TT, Van Dyke ME. 2018. Discrimination and the Health of African Americans: The Potential Importance of Intersectionalities. Current Directions in Psychological Science 27: 176–82 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 72. Lewis TT, Williams DR, Tamene M, Clark CR. 2014. Self-Reported Experiences of Discrimination and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 8: 365. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 73. Lieberson S 1985. Making it Count: The Improvement of Social Research and Theory Berkeley: Univiversity of California Press [ Google Scholar ]

- 74. Link BG, Phelan J. 1995. Social Conditions As Fundamental Causes of Disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior Special Issue: 80–94 [ PubMed ]

- 75. Lukachko A, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM. 2014. Structural racism and myocardial infarction in the United States. Soc Sci Med 103: 42–50 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 76. Maina IW, Belton TD, Ginzberg S, Singh A, Johnson TJ. 2018. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Social Science and Medicine 199: 219–29 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 77. Malat J, Mayorga-Gallo S, Williams DR. 2017. The effects of whiteness on the health of whites in the USA. Social Science & Medicine 199: 148–56 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 78. Mallett CA. 2016. The school-to-prison pipeline: A critical review of the punitive paradigm shift. Child and adolescent social work journal 33: 15–24 [ Google Scholar ]

- 79. Margerison-Zilko C, Perez-Patron M, Cubbin C. 2017. Residential segregation, political representation, and preterm birth among U.S.- and foreign-born Black women in the U.S. 2008–2010. Health Place 46: 13–20 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 80. Martinez O, Wu E, Sandfort T, Dodge B, Carballo-Dieguez A, et al. 2015. Evaluating the impact of immigration policies on health status among undocumented immigrants: a systematic review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 17: 947–70 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 81. Massey DS. 2004. Segregation and stratification: a biosocial perspective. Du Bois Review 1: 7–25 [ Google Scholar ]

- 82. Massey DS. 2016. Segregation and the Perpetuation of Disadvantage. In The Oxford Handbook of the Social Science of Poverty, ed. Brady D, Burton LM New York: Oxford University Press [ Google Scholar ]

- 83. Massey DS, Denton NA. 1988. The dimensions of residential segregation. Social forces 67: 281–315 [ Google Scholar ]

- 84. Mauer M, Huling T. 1995. Young black Americans and the criminal justice system: Five years later, The Sentencing Project [ Google Scholar ]

- 85. Mehra R, Boyd LM, Ickovics JR. 2017. Racial residential segregation and adverse birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine 191: 237–50 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 86. Mendez DD, Hogan VK, Culhane JF. 2014. Institutional racism, neighborhood factors, stress, and preterm birth. Ethnicity & health 19: 479–99 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 87. Miranda ML, Maxson P, Edwards S. 2009. Environmental contributions to disparities in pregnancy outcomes. Epidemiol Rev 31: 67–83 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 88. Monk EP Jr. 2015. The Cost of Color: Skin Color, Discrimination, and Health among African-Americans. American Journal of Sociology 121: 396–444 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 89. Morey BN, Gee GC, Muennig P, Hatzenbuehler ML. 2018. Community-level prejudice and mortality among immigrant groups. Social Science and Medicine 199: 56–66 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 90. Novak NL, Geronimus AT, Martinez-Cardoso AM. 2017. Change in birth outcomes among infants born to Latina mothers after a major immigration raid. Int J Epidemiol 46: 839–49 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 91. Orfield G, Frankenberg E, Garces LM. 2008. Statement of American social scientists of research on school desegregation to the US Supreme Court in Parents v. Seattle School District and Meredith v. Jefferson County. The Urban Review 40: 96–136 [ Google Scholar ]

- 92. Orr MG, Kaplan GA, Galea S. 2016. Neighbourhood food, physical activity, and educational environments and black/white disparities in obesity: a complex systems simulation analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 70: 862–7 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 93. Pager D, Shepherd H. 2008. The Sociology of Discrimination: Racial Discrimination in Employment, Housing, Credit, and Consumer Markets. Annual Review of Sociology 34: 181–209 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 94. Paradies Y 2005. Anti-Racism and Indigenous Australians. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 5: 1–28 [ Google Scholar ]

- 95. Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, et al. 2015. Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE 10: 1–48 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 96. Pascoe EA, Richman LS. 2009. Perceived Discrimination and Health: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychological Bulletin 135: 531–54 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 97. Perreira KM, Telles EE. 2014. The color of health: Skin color, ethnoracial classification, and discrimination in the health of Latin Americans. Social Science & Medicine 116: 241–50 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 98. Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. 2006. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90: 751–83 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 99. Phelan JC, Link BG. 2015. Is Racism a Fundamental Cause of Inequalities in Health? Annual Review of Sociology 41: 311–30 [ Google Scholar ]

- 100. Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. 2010. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav 51 Suppl: S28–40 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 101. Pool LR, Carnethon MR, Goff DC Jr., Gordon-Larsen P, Robinson WR, Kershaw KN 2018. Longitudinal Associations of Neighborhood-level Racial Residential Segregation with Obesity Among Blacks. Epidemiology 29: 207–14 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]