Self-reflection: Foundation for meaningful nursing practice

- Pattern recognition

- Similarity recognition

- Common sense and understanding

- Skilled know-how

- A sense of salience

- Deliberate rationality

- mental health

- RNL Feature

This site uses cookies to keep track of your information. Learn more here . Accept and close .

- Click here - to use the wp menu builder

- Privacy Policy

- Refund Policy

- Terms Of Service

- Nursing notes PDF

- Nursing Foundations

- Medical Surgical Nursing

- Maternal Nursing

- Pediatric Nursing

- Behavioural sciences

- BSC NURSING

- GNM NURSING

- MSC NURSING

- PC BSC NURSING

- HPSSB AND HPSSC

- Nursing Assignment

Reflective Practice in Nursing: A Guide to Improving Patient Care

Reflective Practice in Nursing: A Guide to Improving Patient Care -Reflective practice is an important aspect of nursing that involves the critical analysis of one’s own experiences and actions to improve nursing practice. It is a process of self-reflection and self-evaluation that can lead to personal and professional growth. This article will explore the concept of reflective practice in nursing, its importance in nursing practice, and the strategies and tools that can be used to facilitate reflective practice.

Table of Contents

Understanding Reflective Practice

The definition and concept.

Reflective practice refers to the intentional process of evaluating one’s experiences, thoughts, and actions to gain a deeper understanding of their impact. In nursing, it’s about analyzing the why and how behind every action taken, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of one’s performance.

Historical Context

The roots of reflective practice in nursing can be traced back to the work of influential theorists like Donald Schön, who emphasized the significance of “reflection-in-action” and “reflection-on-action.” These concepts laid the foundation for integrating self-reflection into nursing practice.

Concept of Reflective Practice in Nursing

Reflective practice in nursing is a process of self-reflection and self-evaluation that involves analyzing one’s own experiences and actions to improve nursing practice. It is a way of learning from experiences, both positive and negative, to improve future practice. Reflective practice is based on the assumption that nurses can improve their practice by reflecting on their experiences and critically analyzing their own actions.

Importance of Reflective Practice in Nursing

Reflective practice is important in nursing practice for several reasons. Firstly, it helps nurses to improve their practice by identifying areas for improvement and developing strategies to address them. Secondly, it can enhance nurses’ critical thinking skills by encouraging them to analyze their own experiences and consider different perspectives. Thirdly, it can promote self-awareness and personal growth by encouraging nurses to reflect on their own values and beliefs and how they influence their practice .

There are many benefits to reflective practice in nursing. It can help nurses to:

- Improve patient care outcomes

- Develop critical thinking skills

- Enhance communication skills

- Increase self-awareness

- Promote professional growth and development

- Cope with stress and burnout

Strategies and Tools for Facilitating Reflective Practice

There are several strategies and tools that can be used to facilitate reflective practice in nursing. Some of these include:

- Journaling: Journaling is a common tool used in reflective practice. Nurses can use a journal to record their thoughts and experiences, and then reflect on them to identify areas for improvement.

- Critical Incident Analysis: Critical incident analysis involves reflecting on a specific event or experience in practice and analyzing it to identify strengths and areas for improvement.

- Reflection on Action and Reflection in Action: Reflection on action involves reflecting on past experiences and analyzing them to identify areas for improvement. Reflection in action involves reflecting on experiences as they are happening and making adjustments to practice in real time.

- Peer Reflection: Peer reflection involves discussing experiences and actions with colleagues to gain different perspectives and insights.

- Feedback: Feedback from colleagues, supervisors, and patients can be a valuable tool for reflective practice, providing insight into areas for improvement.

- Professional Development: Professional development activities, such as attending conferences and workshops, can provide opportunities for nurses to learn and reflect on their practice.

Implementing Reflective Practice

Models of reflective practice.

Several models guide nurses through the reflective process. The Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle, for instance, involves stages like description, feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusion, and action plan. These models provide a structured framework for introspection.

Steps in the Reflective Process

- Description: Recount the situation or experience in detail.

- Feelings: Examine your emotions during the event.

- Evaluation: Assess the positives and negatives of the situation.

- Analysis: Dig deeper into the factors influencing your actions.

- Conclusion: Sum up the insights gained from reflection.

- Action Plan: Define steps for future improvements.

Example of Reflective Practice in Nursing

As a registered nurse working in a busy hospital, I recently had an experience that highlighted the importance of reflective practice in improving patient communication and overall care. This incident prompted me to consider my approach to patient interactions and how it could be refined for better outcomes.

In this particular situation, I was assigned to care for a patient who was admitted for a complex surgical procedure. The patient, Mrs. Johnson, appeared anxious and had numerous questions about the upcoming surgery. Due to the high patient load, I felt a sense of time pressure and inadvertently rushed through her questions, providing concise answers without fully addressing her concerns.

Later that day, I engaged in reflective practice, realizing that my approach might not have been the most effective way to support Mrs. Johnson during such a critical time. I used the Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle to guide my self-examination:

- Description: I recalled the interaction with Mrs. Johnson and the rushed manner in which I answered her questions.

- Feelings: I acknowledged that my actions might have contributed to her anxiety and dissatisfaction.

- Evaluation: I assessed the negative impact of my approach on patient communication and the potential consequences for her overall well-being.

- Analysis: I delved into the factors that influenced my behavior, such as time constraints and a high workload.

- Conclusion: I concluded that while these factors were present, they should not have compromised the quality of patient care and communication.

- Action Plan: I determined that in future interactions, I would allocate dedicated time to address patient concerns, ensuring they feel heard and valued.

This reflective process led me to take actionable steps to improve my patient communication skills. In subsequent interactions with Mrs. Johnson, I intentionally created a calm and attentive environment. I provided her with detailed explanations about the surgery, and potential outcomes, and addressed her concerns with empathy. I also encouraged her to ask questions and clarified any doubts she had.

The impact of this reflective practice was profound. Mrs. Johnson’s anxiety visibly decreased, and she expressed gratitude for the time I spent addressing her concerns. Her positive feedback not only boosted her confidence but also reminded me of the significant role effective communication plays in fostering trust between nurses and patients.

This experience taught me that reflective practice isn’t just a theoretical concept but a practical tool that can transform patient care. By taking the time to analyze our interactions, understand our emotions, and make conscious efforts to improve, nurses can create meaningful connections with patients and enhance their overall well-being.

Barriers to Reflective Practice

Despite the importance of reflective practice in nursing, there are several barriers that can make it difficult to implement. Some of these include:

- Time constraints: Nurses may feel that they do not have enough time to engage in reflective practice due to heavy workloads.

- Lack of support: Nurses may not receive support from colleagues or supervisors for engaging in reflective practice.

- Fear of judgment: Nurses may feel uncomfortable reflecting on their experiences and actions for fear of being judged.

- Lack of training: Nurses may not have received adequate training in reflective practice, making it difficult to engage in the process.

Reflective practice is an important aspect of nursing that can lead to personal and professional growth. It involves the critical analysis of one’s own experiences and actions to improve nursing practice. Strategies and tools for facilitating reflective practice include journaling, critical incident analysis, peer reflection, and professional development. However, there are several barriers that can make it difficult to implement reflective practice, including time constraints, lack of support, fear of judgment, and lack of training. Despite these barriers, it is important for nurses to engage in reflective practice to improve their practice and promote positive patient outcomes.

Please note that this article is for informational purposes only and should not substitute professional medical advice.

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recent articles

4 basic techniques of physical examination in nursing., duties and responsibilities of midwife, multifoetal pregnancy complications nursing interventions, typhoid fever care plan, nursing course admission eligibility, what is the cause of cleft palate, download nursing notes pdf, male and female reproductive system pdf, human skeletal system nursing, staff nurse syllabus and exam pattern question bank -ii, pgi staff nurse exam question bank -1, anatomy and physiology of female reproductive system, human physiology digestion and absorption, anatomy and physiology the cardiovascular system nursing notes, hpssc staff nurse exam study material, more like this, what is a nursing diagnosis, what is acute care: a comprehensive guide, the importance of genetics in nursing, the role and qualities of mental health and psychiatric nurses, mental health nursing diagnosis care plan pdf, child pediatric health nursing notes -bsc nursing, mid-wifery pdf notes for nursing students, national health programmes in india pdf, reproductive system nursing notes pdf, primary health care nursing notes pdf, psychology note nursing pdf, nursingenotes.com.

- STUDY NOTES

- SUBJECT NOTES

A Digital Platform For Nursing Study Materials

Latest Articles

How nurses help the community, gifts for nursing home residents, gift ideas for nursing students, most popular.

© Nursingenotes.com | All rights reserved |

- Open access

- Published: 16 March 2023

Effectiveness of a critical reflection competency program for clinical nurse educators: a pilot study

- Sujin Shin 1 ,

- Inyoung Lee 2 ,

- Jeonghyun Kim 3 ,

- Eunyoung Oh 4 &

- Eunmin Hong 1

BMC Nursing volume 22 , Article number: 69 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

9 Citations

Metrics details

Critical reflection is an effective learning strategy that enhances clinical nurses’ reflective practice and professionalism. Therefore, training programs for nurse educators should be implemented so that critical reflection can be applied to nursing education. This study aimed to investigate the effects of a critical reflection competency program for clinical nurse educators on improving critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy.

A pilot study was conducted using a pre- and post-test control-group design. Participants were clinical nurse educators recruited using a convenience sampling method. The program was conducted once a week for 90 min, with a total of four sessions. The effectiveness of the developed program was verified by analyzing pre- and post-test results of 26 participants in the intervention group and 27 participants in the control group, respectively. The chi-square test, independent t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, and analysis of covariance with age as a covariate were conducted.

The critical thinking disposition and teaching efficacy of the intervention group improved after the program, and the differences between the control and intervention groups were statistically significant (F = 14.751, p < 0.001; F = 11.047, p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the change in nursing reflection competency between the two groups (F = 2.674, p = 0.108).

The critical reflection competency program was effective in improving the critical thinking disposition and teaching efficacy of nurse educators. Therefore, it is necessary to implement the developed program for nurse educators to effectively utilize critical reflection in nursing education.

Peer Review reports

The critical thinking of clinical nurses is essential for identifying the needs of patients and providing safe care through prompt and accurate judgment [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Critical thinking can be practiced through critical reflection [ 4 ], a dynamic process in which nurses reflect on their nursing behavior to improve their perspective on a situation and change future nursing practices in a desirable direction [ 5 ]. Through critical reflection, nurses grasp the contextual meaning of a situation and reconstruct their experiences to apply their learning in practice, thereby identifying the meaning of nursing [ 3 ]. In other words, critical reflection can help nurses convert their experiences into practical knowledge [ 6 ]. Thus, critical reflection may be an effective learning strategy linking theory and practice in clinical nursing education [ 7 ].

Studies have reported that critical reflection is effective in improving nurses’ reflective practices and professionalism. Teaching methods that use critical reflection can improve nurses’ knowledge, communication skills, and critical thinking abilities [ 1 , 8 , 9 ]. These methods can be effective in improving clinical judgment and problem-solving abilities by providing new nurses with opportunities to apply their theoretical knowledge in clinical practice [ 10 , 11 ]. In addition, critical reflection has positive effects on the professionalism of new graduate nurses and reduces reality shock during the transition from university to clinical practice [ 12 ]. These advantages have led to the increasing application of critical reflection in training programs for new graduate nurses, including nursing residency programs [ 13 , 14 , 15 ].

In order to facilitate new nurses’ reflective thinking and practice by clinical nurse educators, educators must be trained to strengthen their critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection, and teaching efficacy competency. Educators help new nurses adapt and develop their expertise in clinical settings [ 16 , 17 ]. Moreover, continuing education for nurses to improve their teaching competency relates to the satisfaction of learners and nurse educators, which improves the quality of clinical nursing education [ 18 ]. Therefore, opportunities for nurse educators to develop teaching competency for critical reflection in education should be provided [ 19 ] and educational support for nurse educators to improve critical reflection competency is needed.

However, although there have been studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of the educational interventions concerning critical reflection to new nurses, few studies have been conducted on educational interventions on the critical reflection competencies of clinical nurse educators in charge of educating new nurses. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effects of a critical reflection competency program for clinical nurse educators on improving critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy.

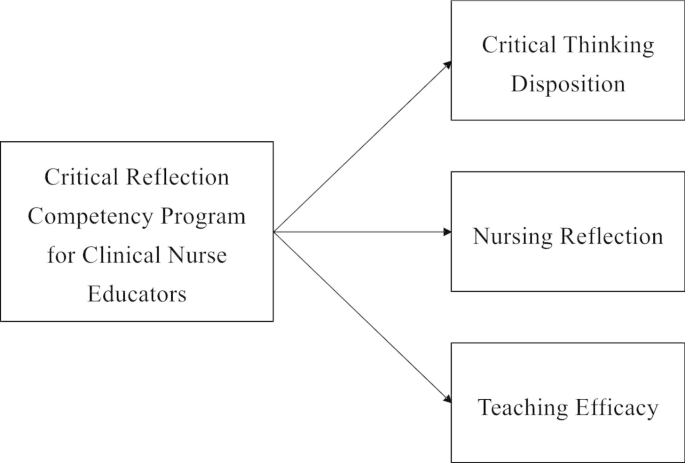

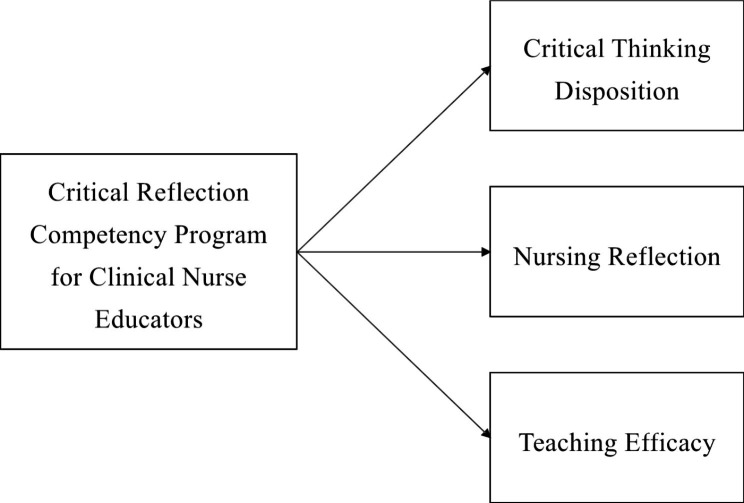

Study design

A pilot study was conducted with a pre- and post-test control group design to investigate the effects of the critical reflection competency program on the critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy of nurse educators. The conceptual framework in this study was proposed that the critical reflection competency program will improve critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection, and teaching efficacy of clinical nurse educators [Fig. 1 ].

Conceptual Framework

Participants were clinical nurse educators in hospitals who were recruited using a convenience sampling method. Nurse educators were eligible to participate if they had dedicated nursing education in a clinical setting. They dedicated to nursing education focused on staff development of current nurses, especially the education for new nurses. They also included those who completed all four sessions of the program and participated in the data collection before and after the program. A recruitment document was sent to hospitals to recruit the participants, hospitals were selected with concerning role of clinical nurse educators. Participants were recruited from two hospitals of different sizes and the number of participants differed for each hospital, and they were allocated according to the order of registration.

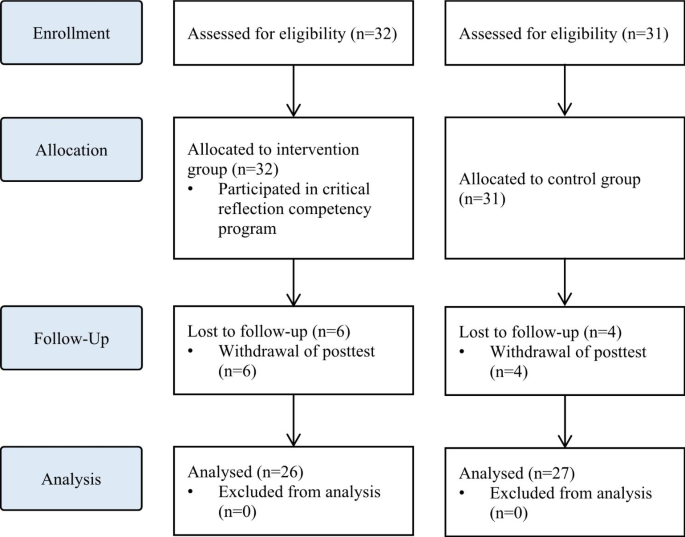

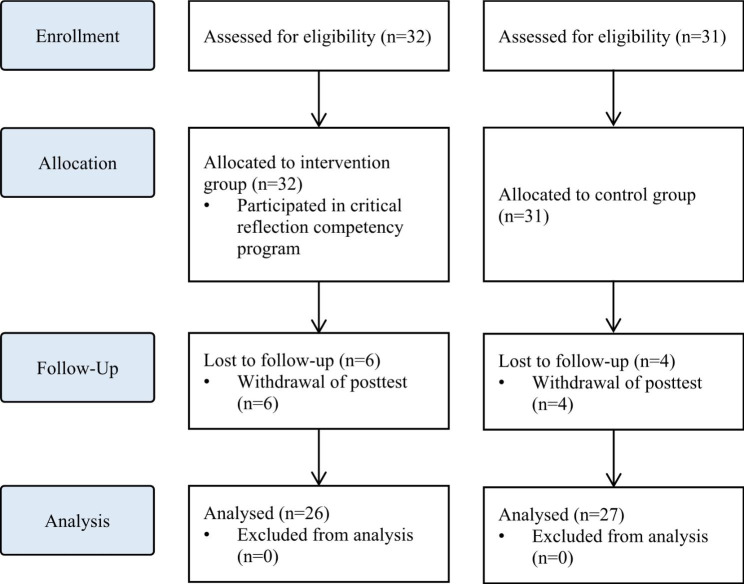

The sample size required for the analysis was calculated using the G* Power 3.1.9.4. program with an effect size of 0.80, a significance level of 0.05, and a power of 0.80, following the literature [ 20 ]. By applying a self-reflection program for intensive care unit nurses [ 20 ], we calculated the effect size as large. Both the intervention and control groups required 26 participants. Considering a dropout rate of 20%, a total of 63 participants, including 32 in the intervention group and 31 in the control group, were recruited. From the intervention group, six participants who participated in the pre-test and completed all programs, but did not participate in the post-test, were excluded. In the control group, four participants who participated in the pre-test but not in the post-test were excluded. Thus, 26 and 27 participants in the intervention and control groups, respectively, were included in the final analysis [Fig. 2 ]. The pre-test for both groups was conducted in May 2021. Post-tests for the two groups were performed four weeks after the pre-test.

Flowchart of the study

Intervention

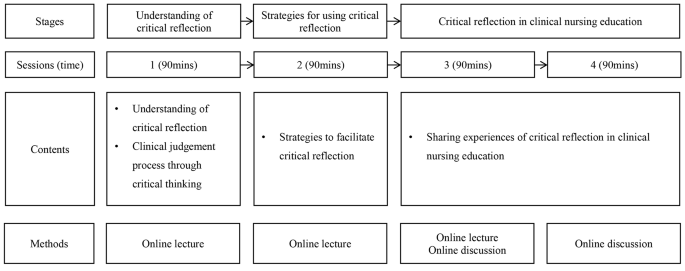

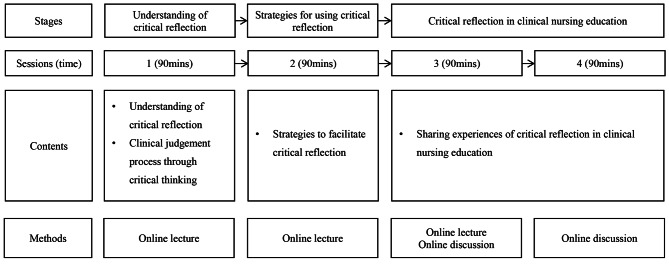

The intervention was developed and delivered by the first author, who has more than 15 years of teaching experience in nursing education, including critical reflection. The intervention was conducted between May 2021 and June 2021. Following previous studies that applied critical reflection in medical education [ 21 , 22 ], the intervention was conducted once a week for 90 min, with a total of four sessions. Owing to COVID-19, real-time online sessions were used to minimize contact between participants working in medical institutions. Every week before the sessions, the contents of the session, schedule, and Uniform Resource Locator (URL) were sent to participants via e-mail.

The intervention consisted of the following three steps in four sessions: (1) understanding critical reflection, (2) strategies to use critical reflection, and (3) practical uses of critical reflection [Fig. 3 ]. Synchronous online lectures were conducted in the first and second sessions. The contents of the first session included understanding of critical reflection and the clinical judgment process through critical reflection. Based on the content of the first session, the second outlined educational strategies using critical reflection in nursing education and the direction of critical reflection. In the third and fourth sessions, clinical nurses with experience of critically reflecting on themselves were invited as guest speakers to share their experiences and facilitate online discussions. Online discussions were also conducted in real time, and feedback from guest speakers and the author was immediately provided.

Critical reflection program for clinical nurse educators

Online self-report surveys were conducted before and after the program to assess the program’s effects. In both pre- and post-tests, critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy were assessed, as well as information about participants, such as gender, age, experience in nursing education, and the type of institution and the number of beds they affiliated with.

Critical thinking disposition was measured using Yoon’s Critical Thinking Disposition Scale [ 23 ]. This scale comprises 27 items: 5 on “intellectual eagerness/curiosity,” 4 on “prudence,” 4 on “self-confidence,” 3 on “systematicity,” 4 on “intellectual fairness,” 4 on “healthy skepticism,” and 3 on “objectivity.” The items were evaluated on a five-point Likert scale (one point for “strongly disagree” to five points for “strongly agree”); a higher score indicated greater critical thinking disposition. The scale has good reliability as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84 at the time of the development versus the reliability of the scale in this study was Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.

Nursing reflection competency was assessed using the Nursing-Reflection Questionnaire, developed by Lee et al. [ 24 ]. This scale comprises four factors with 15 items, including 6 items on “review and analysis nursing behavior,” 5 on “development-oriented deliberative engagement,” 2 on “objective self-awareness,” and 2 on “contemplation of behavioral change.” Each item was evaluated on a five-point Likert scale (one point for “strongly disagree” to five points for “strongly agree”), with a higher score indicating greater nursing reflection competency. The scale has good reliability as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86 at the time of the development versus the reliability of the scale in this study was Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82.

Teaching efficacy was evaluated using the Teaching Efficacy Scale developed by Park and Suh [ 25 ] to evaluate clinical nursing instructors. This scale consisted of six sub-factors with 42 items, including 12 items on “student instruction,” 9 on “teaching improvement,” 7 on “application of teaching and learning,” 7 on “interpersonal relationship and communication,” 4 on “clinical judgment,” and 3 on “clinical skill instruction.” Each item was evaluated on a five-point Likert scale (one point for “strongly disagree” to five points for “strongly agree”), with a higher score indicating greater teaching efficacy. The scale has good reliability as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.97 at the time of the development versus the reliability of the scale in this study was Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Ewha Womans University (IRB no. ewha-202105-0022-02). The need of written informed consent was exempted by IRB of Ewha Womans University. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. A description of the study, including its purpose, methods, and procedures, was posted on an online pre-test survey. Only those participants who agreed to participate were allowed to complete the questionnaire. The participants were also informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time and that the data of withdrawn participants would not be included in the final analysis. After the survey was completed, a mobile gift voucher was provided to those who agreed to provide their mobile phone number. Data were collected by researchers who did not participate in the program.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows (version 28.0). Non-normally distributed data were analyzed using non-parametric tests. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation of participants’ general and institutional characteristics. Chi-square, independent t-, and Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted to test the homogeneity of the general characteristics and pre-test scores. The Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted to test the normality of the data. To test the difference between the pre- and post-tests for each group, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used. As there was a significant difference in age between the intervention and control groups, an ANCOVA with age as a covariate was conducted for the difference in changes in test scores between the pre- and post-test.

Homogeneity test of general characteristics and dependent variables

All participants were female, with a mean nursing education experience of 27 and 23 months in the intervention and control groups, respectively. The homogeneity test of general and institutional characteristics, such as gender, nursing education experience, affiliated institution types, and the number of beds, were not statistically significant. However, the age differed significantly between the two groups. In the test for homogeneity of the pre-intervention scores, there were no significant differences in critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, or teaching efficacy between the two groups, suggesting homogeneity of the dependent variables between the groups [Table 1 ].

Effects of critical reflection competency program

The effects of the critical reflection competency program are shown in Table 2 .

In the post-intervention phase, scores of critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy all improved compared to the pre-intervention phase, and were higher in the experimental group than in the control group. The critical thinking disposition scores before and after the intervention were 3.61 ± 0.26 vs. 3.87 ± 0.04 in the intervention group and 3.76 ± 0.21 vs. 3.77 ± 0.04 in the control group, respectively. The nursing reflection competency scores before and after the intervention were 57.00 ± 3.42 vs. 60.86 ± 0.95 in the intervention group and 59.63 ± 5.24 vs. 59.04 ± 0.89 in the control group. The teaching efficacy scores before and after the intervention were 157.04 ± 10.60 vs. 171.98 ± 2.54 in the intervention group and 161.59 ± 14.77 vs. 160.48 ± 2.46 in the control group.

Age, which was significantly different between the intervention and control groups, was treated as a covariate to conduct the ANCOVA. The changes in critical thinking disposition (F = 14.751, p < 0.001) and teaching efficacy (F = 11.047, p < 0.001) scores were significantly different between the two groups. However, there was no significant difference in the change in the nursing reflection competency (F = 2.674, p = 0.108) score between the two groups.

Reflective practice is crucial to clinical nurses’ professionalism. Reflective practice enables positive learning experiences through deep and meaningful learning, and is essential for integrating theory and practice. It also enables nurses to implement what they have learned into practice, understand their expertise, and develop clinical competencies [ 26 ]. In this respect, it is important for clinical nursing educators to have critical reflection competencies and promote experiential learning among new nurses. In this study, a critical reflection competency program was developed to enhance clinical nurse educators’ critical thinking and teaching competency.

This program was effective in improving critical thinking disposition. In interventions for critical reflection, various aspects, including the introduction of critical reflection and guidelines to promote critical reflection, such as small group discussions and feedback, can be considered [ 27 ]. The program reflected these aspects and helped improve participants’ critical thinking disposition. In the third and fourth sessions, synchronous discussions on sharing experiences of critical reflection were effective. This is consistent with previous studies in which discussions improved reflective competencies [ 21 , 28 ]. Therefore, sharing experiences in the discussion section should be a key element of future educational interventions for critical reflection competency.

Furthermore, the program was effective in improving teaching efficacy. Teaching efficacy is the instructor’s belief in one’s own ability to organize and implement teaching [ 29 ], and is closely related to age, clinical experience, educational experience, professional development, and teaching competency [ 30 , 31 , 32 ]. Nurses who are more clearly aware of their roles as instructors tend to exhibit higher confidence in their teaching abilities [ 33 , 34 ]. That is, the participants in this study were clearly aware of their roles and developed confidence by sharing their educational experiences about critical reflection.

However, the program did not have a significant effect on nursing reflection competencies. In a previous study [ 10 ], reflective practitioners (RPs) received four weeks of critical reflection training and trained new nurses for six months. During training, new nurses wrote critical reflective journals and RPs provided feedback and shared their experiences. In this study, it seems that the methods and frequency of using critical reflection in nursing education varied for each participant, resulting in insignificant results for nursing reflection competency. It is necessary to provide educational materials or guidelines so that nurse educators can use critical reflection in nursing education.

In this pilot study, the program was found to be effective in improving critical thinking disposition and teaching efficacy. The results show that the program can enhance the critical thinking disposition of nurse educators and help them develop teaching competency by critically reflecting on their educational experiences as instructors [ 35 , 36 ]. Therefore, various educational programs and training systems related to critical reflection are required [ 37 ]. However, many medical institutions find it difficult to provide sufficient educational support to nurses because of limited costs, time, and physical space [ 38 ]. Online real-time lectures and case-based discussions of the developed program can be useful alternatives to overcome barriers to nursing education support. Additionally, more effective educational content and platforms using e-learning can be developed based on the results of this study.

In this study, the critical reflection competency program for clinical nurse educators was developed and conducted. The program was an educational intervention to improve the critical reflection competency of clinical nurse educators in real time online. Several limitations must be considered when interpreting the present findings. The developed program did not affect nursing reflection competencies. Further, the post-test was conducted shortly after program completion. Therefore, there may be limitations to evaluating whether the developed program improves the quality of nursing education. In addition, the participants in this study were allocated regardless of their hospital’s characteristics. Considering variables such as the size of the hospitals, the number of new nurses, and the number of participants per hospital, it is necessary to assign nurse educators the intervention and control groups and to verify the effects of the program. Future studies should consider improving the study design to measure the long-term effects of the program and randomize the participants.

The effects of the program on critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy were assessed. The results showed that the program was effective in improving the critical thinking disposition and teaching efficacy of nurse educators. However, there was no significant difference in nursing reflection competency, but it may vary depending on the methods or time of using critical reflection in nursing education. Therefore, it is necessary to provide the critical reflection utilization strategies that can be used by clinical nurse educators in the clinical settings. In addition, further research, such as evaluating the reflective practice of new nurses trained by clinical nurse educators, is needed. This suggests that the critical reflection competency program should be expanded in the future for nurse educators. It is necessary to develop e-learning content and educational platforms to expand the program, and it should be possible to share the experience of critical reflection in various forms. Also, sufficient support for competency improvement of nurse educators is needed to effectively use critical reflection in nursing education. Nursing leaders in hospital and healthcare settings should recognize the importance of using critical reflection in clinical practice and improving the competency of clinical nursing educators who educate new nurses, and make efforts to improve the quality of nursing education through support for these. Lastly, based on the results of this study, we recommend further longitudinal and randomized studies to evaluate additional effects of the program.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Kim YH, Min J, Kim SH, Shin S. Effects of a work-based critical reflection program for novice nurses. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1135-0 .

Article Google Scholar

Alfaro-LeFevre R. Critical thinking in nursing: a practical approach. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 1995.

Google Scholar

Do J, Shin S, Lee I, Jung Y, Hong E, Lee MS. Qualitative content analysis on critical reflection of clinical nurses. J Qual Res. 2021;22:86–96. https://doi.org/10.22284/qr.2021.22.86 .

Burrell LA. Integrating critical thinking strategies into nursing curricula. Teach Learn Nurs. 2014;9:53–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2013.12.005 .

Lee M, Jang K. Reflection-related research in korean nursing: a literature review. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2019;25:83–96. https://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2019.25.2 .

Cox K. Planning bedside teaching. Med J Aust. 1993;158:280–2. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1993.tb137586.x .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Klaeson K, Berglund M, Gustavsson S. The character of nursing students’ critical reflection at the end of their education. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2017;7:55–61. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v7n5p55 .

Pangh B, Jouybari L, Vakili MA, Sanagoo A, Torik A. The effect of reflection on nurse-patient communication skills in emergency medical centers. J Caring Sci. 2019;8:75–81. https://doi.org/10.15171/jcs.2019.011 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Liu K, Ball AF. Critical reflection and generativity: toward a framework of transformative teacher education for diverse learners. Rev Res Educ. 2019;43:68–105. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X18822806 .

Shin S, Kim SH. Experience of novice nurses participating in critical reflection program. J Qual Res. 2019;20:60–7. https://doi.org/10.22284/qr.2018.20.1.60 .

Lee M, Jang K. The significance and application of reflective practice in nursing practice. J Nurs Health Issues. 2018;23:1–8.

Monagle JL, Lasater K, Stoyles S, Dieckmann N. New graduate nurse experiences in clinical judgment: what academic and practice educators need to know. Nurs Educ Pers. 2018;39:201–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000336 .

Bull R, Shearer T, Youl L, Campbell S. Enhancing graduate nurse transition: report of the evaluation of the clinical honors program. J Cont Educ Nurs. 2018;49:348–55. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20180718-05 .

Cadmus E, Salmond SW, Hassler LJ, Black K, Bohnarczyk N. Creating a long-term care new nurse residency model. J Cont Educ Nurs. 2016;47:234–40. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20160419-10 .

Johansson A, Berglund M, Kjellsdotter A. Clinical nursing introduction program for new graduate nurses in Sweden: study protocol for a prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ open. 2021;11:e042385. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042385 .

Salminen L, Minna S, Sanna K, Jouko K, Helena LK. The competence and the cooperation of nurse educators. Nurse Educ Today., 2013;33:1376–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.09.008 .

Zlatanovic T, Havnes A, Mausethagen S. A research review of nurse teachers’ competencies. Vocations Learn. 2017;10:201 − 33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-016-9169-0 .

Shinners JS, Franqueiro T. Preceptor skills and characteristics: considerations for preceptor education. J Cont Educ Nurs. 2015;46:233–6. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20150420-04 .

Sheppard-Law S, Curtis S, Bancroft J, Smith W, Fernandez R. Novice clinical nurse educator’s experience of a self-directed learning, education and mentoring program: a qualitative study. Contemp Nurs. 2018;54:208–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2018.1482222 .

Kang HJ, Bang KS. Development and evaluation of a self-reflection program for intensive care unit nurses who have experienced the death of pediatric patients. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2017;47:392-405. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2017.47.3.392 .

Hayton A, Kang I, Wong R, Loo LK. Teaching medical students to reflect more deeply. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27:410-6. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2015.1077124 .

Spampinato CM, Wittich CM, Beckman TJ, Cha SS, Pawlina W. Safe Harbor”: evaluation of a professionalism case discussion intervention for the gross anatomy course. Anat Sci Educ. 2014;7:191–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Yoon J. Development of an instrument for the measurement of critical thinking disposition: In nursing[dissertation]. Seoul: Catholic University; 2004.

Lee H. Development and psychometric evaluation of nursing-reflection questionnaire [dissertation]. Seoul: Korea University; 2020.

Park I, Suh YO. Development of teaching efficacy scale to evaluate clinical nursing instructors. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2017;30:18–29. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2018.30.1.18 .

Froneman K, du Plessis E, van Graan AC. Conceptual model for nurse educators to facilitate their presence in large class groups of nursing students through reflective practices: a theory synthesis. BMC Nurs. 2022;21:317. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-022-01095-7 .

Uygur J, Stuart E, De Paor M, Wallace E, Duffy S, O’Shea M, Smith S, Pawlikowska T. A best evidence in medical education systematic review to determine the most effective teaching methods that develop reflection in medical students. BEME Guide No 51 Med Teach. 2019;41:3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1505037 .

McEvoy M, Pollack S, Dyche L, Burton W. Near-peer role modeling: can fourth-year medical students, recognized for their humanism, enhance reflection among second-year students in a physical diagnosis course? Med Educ Online. 2016;21:31940. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v21.31940 .

Poulou M. Personal teaching efficacy and its sources: student teachers’ perceptions. Educ Psychol. 2007;27:191–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410601066693 .

Klopfer BC, Piech EM. Characteristics of effective nurse educators. Sigma Theta Tau International: Leadership Connection 2016; 2016.

Dozier AL. An investigation of nursing faculty teacher efficacy in nursing schools in Georgia. ABNF J. 2019;30:50–7.

Kim EK, Shin S. Teaching efficacy of nurses in clinical practice education: a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;54:64–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.04.017 .

Wu XV, Chi Y, Selvam UP, Devi MK, Wang W, Chan YS, Wee FC, Zhao S, Sehgal V, Ang NKE. A clinical teaching blended learning program to enhance registered nurse preceptors’ teaching competencies: Pretest and posttest study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e18604. https://doi.org/10.2196/18604 .

Larsen R, Zahner SJ. The impact of web-delivered education on preceptor role self-efficacy and knowledge in public health nurses. Public Health Nurs. 2011;28:349–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00933.x .

Armstrong DK, Asselin ME. Supporting faculty during pedagogical change through reflective teaching practice: an innovative approach. Nurs Educ Pers. 2017;38:354–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000153 .

Raymond C, Profetto-McGrath J, Myrick F, Strean WB. Balancing the seen and unseen: nurse educator as role model for critical thinking. Nurse Educ Prac. 2018;31:41–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.04.010 .

Parrish DR, Crookes K. Designing and implementing reflective practice programs–key principles and considerations. Nurse Educ Prac. 2014;14:265–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2013.08.002 .

Glogowska M, Young P, Lockyer L, Moule P. How ‘blended’ is blended learning?: students’ perceptions of issues around the integration of online and face-to-face learning in a continuing professional development (CPD) health care context. Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31:887–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2011.02.003 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1F1A1057096).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Nursing, Ewha Womans University, 52 Ewhayeodae-gil, Seodaemun-gu, 03760, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Sujin Shin & Eunmin Hong

Department of Nursing, Dongnam Health University, 50, Cheoncheon-ro 74beon-gil, Jangan-gu, Suwon-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

Inyoung Lee

College of Nursing, Catholic University of Pusan, 57 Oryundae-ro, Geumjeong-gu, 46252, Busan, Republic of Korea

Jeonghyun Kim

Department of Nursing, Nursing Administration Education Team Leader, Catholic University of Korea Bucheon ST. Mary’s Hospital, 327, Sosa-ro, 14647, Bucheon-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

Eunyoung Oh

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Project administration. IL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. JK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. EO: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. EH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Eunmin Hong .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Ewha Womans University (IRB no. ewha-202105-0022-02). The need of written informed consent was exempted by IRB of Ewha Womans University. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Shin, S., Lee, I., Kim, J. et al. Effectiveness of a critical reflection competency program for clinical nurse educators: a pilot study. BMC Nurs 22 , 69 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01236-6

Download citation

Received : 12 December 2022

Accepted : 07 March 2023

Published : 16 March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01236-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Education professional

- Nursing education research

- Program evaluation

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Critical self-reflection for nurse educators: Now more than ever!

Affiliation.

- 1 Malta College of Arts, Science and Technology (MCAST), Institute of Applied Sciences Corradino Hill, Paola, PLA9032 Malta.

- PMID: 33013247

- PMCID: PMC7522740

- DOI: 10.1016/j.teln.2020.09.001

The dynamic healthcare world and increased demands on nurses call for a parallel shift in nursing education that is optimally geared toward effectiveness. Just as student nurses are taught to reflect on their practice to effectively meet clients' needs, educators also need to be well versed in self-reflection to enhance their teaching methods. Self-reflection is the deliberate consideration of experiences, which when guided by the literature helps an individual gain insight and improve practice. Educators should not only opt for personal reflection but should also seek the views of their students and peers. Self-reflection becomes critical when it goes beyond mere reflection, questioning teaching assumptions, and addressing their social and political context. Given the remarked benefits of using self-reflection in education, and the current COVID-19 global repercussions which have urged faculties to try alternative methods of teaching, a concise guide to self-reflection is hereby provided for use by nurse educators.

Keywords: COVID-19; Nursing education; Nursing faculty; Reflection.

© 2020 Organization for Associate Degree Nursing. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Why Self-Reflection Is Critical In Nursing Education—Drive Lifelong Learning and Future Success

As future healthcare providers, nursing students not only need to master a rigorous curriculum and complex concepts but also develop a wide range of clinical skills and knowledge to deliver high-quality patient care. Several characteristics have been identified as key to optimizing nursing care, including self-motivation, positive workplace culture, and a strong enabling leadership. 1

Another skill that has emerged as critical in nursing education is self-reflection, which involves accurately identifying and analyzing one’s thoughts, actions, and feelings, requiring cognitive activities such as description, critical analysis, evaluation, and planning. When applied to practice, it improves nurses’ self-efficacy and work engagement 2 —values that enable high-quality patient care. One study found significant and positive correlations between these three qualities.

For more ways to help your nursing students develop self-reflection, download our Educator Guide: How Educators Can Foster Self-Reflection in Healthcare Learning—and Empower Learners to Become Successful Practitioners

The connection between self-reflection, self-efficacy, and work engagement

Using a stratified random sampling method and inclusion criteria that included holding a bachelor’s degree in nursing and clinical working experience, a total of 240 nurses from seven hospitals were selected for the study. 3 Data were collected via three questionnaires: Groningen Reflection Ability Scale (GRAS), Sherer’s General Self-Efficacy Scale (SGSES), and Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES).

Overall, the nurses’ total reflection scores were found to correlate positively and significantly with their work engagement and self-efficacy levels.

Does this suggest that nursing students should be encouraged to cultivate this practice from the start of their program and in clinical settings? Let’s take a closer look at key findings from the study.

Self-reflection

The nurses in the study exhibited a robust reflective practice, as indicated by a relatively high level of reflection—the mean score was 86.51 out of 115. Notably, there was a statistically significant difference in the reflection scores of nurses working in the emergency department (ED) compared to nurses in other departments; ED nurses had a higher mean score.

Why this is important

Self-reflection has an essential role in nursing education and practice: it facilitates the learning of clinical nurses, boosts the quality of care provided, and encourages nurses to search for and discover solutions to difficult situations. Through self-reflection, nurses gain new experiences and insights from both clinical and educational settings. This process helps them develop a sense of ownership over the acquired knowledge, enhancing their expertise and clinical decision-making. 4

Self-efficacy

The nurses demonstrated a high level of self-efficacy—60.89 out of 85—and similar to self-reflection, ED nurses had a higher mean score than their counterparts in other departments. Additionally, there was a statistically significant correlation between self-efficacy with age and years of work experience, underscoring the value of experience in building confidence and capability in clinical practice.

The self-efficacy theory is based on the premise that individuals’ beliefs about their abilities positively influence their actions and activities. Nurses with high self-efficacy are more motivated, provide higher quality patient care, and can more effectively overcome challenges due to their enhanced problem-solving skills. When faced with difficulties, these nurses focus on their abilities to find solutions and navigate situations successfully.

Work engagement

The study indicated that the mean work engagement score among nurses was 3.39 out of 6. Engaged nurses are more likely to experience job satisfaction, which can lead to higher retention rates and improved patient care outcomes.

Work engagement refers to an individual’s commitment to their organization or employer and has a positive effect on both employee performance and organizational outcomes. Key variables influenced by work engagement include job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and work performance, and they encompass feelings of vigor and identification with work activities.

Pearson correlation matrix showing the correlation between nurses’ reflection, self-efficacy, and work engagement level

The results of the study indicated a positive and significant relationship between self-reflection, self-efficacy, and work engagement among nurses: the mean score for each rose in tandem with the others. This is consistent with another study that reported high self-reflection scores corresponded with high self-efficacy scores 5 while a study on ICU (intensive care unit) nurses 6 showed a significant correlation between self-reflection and work engagement.

What Does This Mean for Nursing Education?

Self-reflection brings about many positive consequences for nurses, including supporting the development of lifelong learning habits for optimum personal and professional development; enabling them to deliver better quality of patient care and support; and boosting knowledge, attitude, and practices regarding ethical codes, leading to improved clinical competency.

Thus, self-reflection should be integrated into nursing education so that students can start building these qualities from day one of nursing school and sharpen them across their journey toward licensure and in future practice.

Programs and faculty can help nursing students cultivate self-reflection by pairing learning science-based resources such as Picmonic’s 1,300+ audio-visual mnemonic video lessons and TrueLearn’s NCLEX-style critical thinking questions with self-reflection practices to:

- Get immediate, real-time feedback on performance and comprehension

- Interact meaningfully with the content (active learning), improve long-term retention and ease of recall

- Identify learning strengths and weaknesses, pinpoint areas for improvement

- Track and measure learning progress and exam readiness longitudinally

- Adjust/tailor teaching/study methods for the most effective, efficient learning

Learn more about a partnership with TrueLearn and Picmonic here.

Help your nursing students achieve optimal exam performance and outcomes, read and share this blog with them and encourage them to utilize our free Post-Assessment Self-Reflection Questionnaire!

1 King R, Taylor B, Talpur A, et al. Factors that optimise the impact of continuing professional development in nursing: A rapid evidence review. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;98(104652):104652. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104652

2 Tbzmed.ac.ir. Accessed July 24, 2024. https://jcs.tbzmed.ac.ir/Article/jcs-31920

3 Zarrin L, Ghafourifard M, Sheikhalipour Z. Relationship between nurses reflection, self-efficacy and work engagement: A multicenter study. J Caring Sci. 2023;12(3):155-162. doi:10.34172/jcs.2023.31920

4 Razieh S, Somayeh G, Fariba H. Effects of reflection on clinical decision-making of intensive care unit nurses. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;66:10-14. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2018.03.009

5 Sundgren MKM, Dawber C, Millear PM, Medoro L. Reflective practice groups and nurse professional quality of life. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2021;38(4). doi:10.37464/2020.384.355

6 Lawrence LA. Work engagement, moral distress, education level, and critical reflective practice in intensive care nurses: Critical reflective practice in intensive care nurses. Nurs Forum. 2011;46(4):256-268. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6198.2011.00237.x

Related Content

Empower Nurse Educators to Fight Nursing Student Attrition a...

Fighting Nurse Attrition with Science-Backed Audio-Visual Mn...

Five Ways Picmonic Benefits Nursing Students and Faculty

Subscribe to TrueLearn's Newsletter

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Effectiveness of a critical reflection competency program for clinical nurse educators: a pilot study

Inyoung lee, jeonghyun kim, eunyoung oh, eunmin hong.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2022 Dec 12; Accepted 2023 Mar 7; Collection date 2023.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Critical reflection is an effective learning strategy that enhances clinical nurses’ reflective practice and professionalism. Therefore, training programs for nurse educators should be implemented so that critical reflection can be applied to nursing education. This study aimed to investigate the effects of a critical reflection competency program for clinical nurse educators on improving critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy.

A pilot study was conducted using a pre- and post-test control-group design. Participants were clinical nurse educators recruited using a convenience sampling method. The program was conducted once a week for 90 min, with a total of four sessions. The effectiveness of the developed program was verified by analyzing pre- and post-test results of 26 participants in the intervention group and 27 participants in the control group, respectively. The chi-square test, independent t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, and analysis of covariance with age as a covariate were conducted.

The critical thinking disposition and teaching efficacy of the intervention group improved after the program, and the differences between the control and intervention groups were statistically significant (F = 14.751, p < 0.001; F = 11.047, p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the change in nursing reflection competency between the two groups (F = 2.674, p = 0.108).

The critical reflection competency program was effective in improving the critical thinking disposition and teaching efficacy of nurse educators. Therefore, it is necessary to implement the developed program for nurse educators to effectively utilize critical reflection in nursing education.

Keywords: Education professional, Nurses, Nursing education research, Program evaluation

The critical thinking of clinical nurses is essential for identifying the needs of patients and providing safe care through prompt and accurate judgment [ 1 – 3 ]. Critical thinking can be practiced through critical reflection [ 4 ], a dynamic process in which nurses reflect on their nursing behavior to improve their perspective on a situation and change future nursing practices in a desirable direction [ 5 ]. Through critical reflection, nurses grasp the contextual meaning of a situation and reconstruct their experiences to apply their learning in practice, thereby identifying the meaning of nursing [ 3 ]. In other words, critical reflection can help nurses convert their experiences into practical knowledge [ 6 ]. Thus, critical reflection may be an effective learning strategy linking theory and practice in clinical nursing education [ 7 ].

Studies have reported that critical reflection is effective in improving nurses’ reflective practices and professionalism. Teaching methods that use critical reflection can improve nurses’ knowledge, communication skills, and critical thinking abilities [ 1 , 8 , 9 ]. These methods can be effective in improving clinical judgment and problem-solving abilities by providing new nurses with opportunities to apply their theoretical knowledge in clinical practice [ 10 , 11 ]. In addition, critical reflection has positive effects on the professionalism of new graduate nurses and reduces reality shock during the transition from university to clinical practice [ 12 ]. These advantages have led to the increasing application of critical reflection in training programs for new graduate nurses, including nursing residency programs [ 13 – 15 ].

In order to facilitate new nurses’ reflective thinking and practice by clinical nurse educators, educators must be trained to strengthen their critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection, and teaching efficacy competency. Educators help new nurses adapt and develop their expertise in clinical settings [ 16 , 17 ]. Moreover, continuing education for nurses to improve their teaching competency relates to the satisfaction of learners and nurse educators, which improves the quality of clinical nursing education [ 18 ]. Therefore, opportunities for nurse educators to develop teaching competency for critical reflection in education should be provided [ 19 ] and educational support for nurse educators to improve critical reflection competency is needed.

However, although there have been studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of the educational interventions concerning critical reflection to new nurses, few studies have been conducted on educational interventions on the critical reflection competencies of clinical nurse educators in charge of educating new nurses. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effects of a critical reflection competency program for clinical nurse educators on improving critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy.

Study design

A pilot study was conducted with a pre- and post-test control group design to investigate the effects of the critical reflection competency program on the critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy of nurse educators. The conceptual framework in this study was proposed that the critical reflection competency program will improve critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection, and teaching efficacy of clinical nurse educators [Fig. 1 ].

Conceptual Framework

Participants were clinical nurse educators in hospitals who were recruited using a convenience sampling method. Nurse educators were eligible to participate if they had dedicated nursing education in a clinical setting. They dedicated to nursing education focused on staff development of current nurses, especially the education for new nurses. They also included those who completed all four sessions of the program and participated in the data collection before and after the program. A recruitment document was sent to hospitals to recruit the participants, hospitals were selected with concerning role of clinical nurse educators. Participants were recruited from two hospitals of different sizes and the number of participants differed for each hospital, and they were allocated according to the order of registration.

The sample size required for the analysis was calculated using the G* Power 3.1.9.4. program with an effect size of 0.80, a significance level of 0.05, and a power of 0.80, following the literature [ 20 ]. By applying a self-reflection program for intensive care unit nurses [ 20 ], we calculated the effect size as large. Both the intervention and control groups required 26 participants. Considering a dropout rate of 20%, a total of 63 participants, including 32 in the intervention group and 31 in the control group, were recruited. From the intervention group, six participants who participated in the pre-test and completed all programs, but did not participate in the post-test, were excluded. In the control group, four participants who participated in the pre-test but not in the post-test were excluded. Thus, 26 and 27 participants in the intervention and control groups, respectively, were included in the final analysis [Fig. 2 ]. The pre-test for both groups was conducted in May 2021. Post-tests for the two groups were performed four weeks after the pre-test.

Flowchart of the study

Intervention

The intervention was developed and delivered by the first author, who has more than 15 years of teaching experience in nursing education, including critical reflection. The intervention was conducted between May 2021 and June 2021. Following previous studies that applied critical reflection in medical education [ 21 , 22 ], the intervention was conducted once a week for 90 min, with a total of four sessions. Owing to COVID-19, real-time online sessions were used to minimize contact between participants working in medical institutions. Every week before the sessions, the contents of the session, schedule, and Uniform Resource Locator (URL) were sent to participants via e-mail.

The intervention consisted of the following three steps in four sessions: (1) understanding critical reflection, (2) strategies to use critical reflection, and (3) practical uses of critical reflection [Fig. 3 ]. Synchronous online lectures were conducted in the first and second sessions. The contents of the first session included understanding of critical reflection and the clinical judgment process through critical reflection. Based on the content of the first session, the second outlined educational strategies using critical reflection in nursing education and the direction of critical reflection. In the third and fourth sessions, clinical nurses with experience of critically reflecting on themselves were invited as guest speakers to share their experiences and facilitate online discussions. Online discussions were also conducted in real time, and feedback from guest speakers and the author was immediately provided.

Critical reflection program for clinical nurse educators

Online self-report surveys were conducted before and after the program to assess the program’s effects. In both pre- and post-tests, critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy were assessed, as well as information about participants, such as gender, age, experience in nursing education, and the type of institution and the number of beds they affiliated with.

Critical thinking disposition was measured using Yoon’s Critical Thinking Disposition Scale [ 23 ]. This scale comprises 27 items: 5 on “intellectual eagerness/curiosity,” 4 on “prudence,” 4 on “self-confidence,” 3 on “systematicity,” 4 on “intellectual fairness,” 4 on “healthy skepticism,” and 3 on “objectivity.” The items were evaluated on a five-point Likert scale (one point for “strongly disagree” to five points for “strongly agree”); a higher score indicated greater critical thinking disposition. The scale has good reliability as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84 at the time of the development versus the reliability of the scale in this study was Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.

Nursing reflection competency was assessed using the Nursing-Reflection Questionnaire, developed by Lee et al. [ 24 ]. This scale comprises four factors with 15 items, including 6 items on “review and analysis nursing behavior,” 5 on “development-oriented deliberative engagement,” 2 on “objective self-awareness,” and 2 on “contemplation of behavioral change.” Each item was evaluated on a five-point Likert scale (one point for “strongly disagree” to five points for “strongly agree”), with a higher score indicating greater nursing reflection competency. The scale has good reliability as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86 at the time of the development versus the reliability of the scale in this study was Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82.

Teaching efficacy was evaluated using the Teaching Efficacy Scale developed by Park and Suh [ 25 ] to evaluate clinical nursing instructors. This scale consisted of six sub-factors with 42 items, including 12 items on “student instruction,” 9 on “teaching improvement,” 7 on “application of teaching and learning,” 7 on “interpersonal relationship and communication,” 4 on “clinical judgment,” and 3 on “clinical skill instruction.” Each item was evaluated on a five-point Likert scale (one point for “strongly disagree” to five points for “strongly agree”), with a higher score indicating greater teaching efficacy. The scale has good reliability as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.97 at the time of the development versus the reliability of the scale in this study was Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Ewha Womans University (IRB no. ewha-202105-0022-02). The need of written informed consent was exempted by IRB of Ewha Womans University. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. A description of the study, including its purpose, methods, and procedures, was posted on an online pre-test survey. Only those participants who agreed to participate were allowed to complete the questionnaire. The participants were also informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time and that the data of withdrawn participants would not be included in the final analysis. After the survey was completed, a mobile gift voucher was provided to those who agreed to provide their mobile phone number. Data were collected by researchers who did not participate in the program.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows (version 28.0). Non-normally distributed data were analyzed using non-parametric tests. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation of participants’ general and institutional characteristics. Chi-square, independent t-, and Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted to test the homogeneity of the general characteristics and pre-test scores. The Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted to test the normality of the data. To test the difference between the pre- and post-tests for each group, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used. As there was a significant difference in age between the intervention and control groups, an ANCOVA with age as a covariate was conducted for the difference in changes in test scores between the pre- and post-test.

Homogeneity test of general characteristics and dependent variables

All participants were female, with a mean nursing education experience of 27 and 23 months in the intervention and control groups, respectively. The homogeneity test of general and institutional characteristics, such as gender, nursing education experience, affiliated institution types, and the number of beds, were not statistically significant. However, the age differed significantly between the two groups. In the test for homogeneity of the pre-intervention scores, there were no significant differences in critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, or teaching efficacy between the two groups, suggesting homogeneity of the dependent variables between the groups [Table 1 ].

Homogeneity test on general characteristics and dependent variables (N = 53)

* Independent t-test; ** Chi-square test; *** Mann-Whitney U test; Exp.=experimental group; Cont.=control group

Effects of critical reflection competency program

The effects of the critical reflection competency program are shown in Table 2 .

Effects of critical reflection competency program (N = 53)

* Ranked ANCOVA; Exp.=experimental group; Cont.=control group; LSM = least mean square

In the post-intervention phase, scores of critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy all improved compared to the pre-intervention phase, and were higher in the experimental group than in the control group. The critical thinking disposition scores before and after the intervention were 3.61 ± 0.26 vs. 3.87 ± 0.04 in the intervention group and 3.76 ± 0.21 vs. 3.77 ± 0.04 in the control group, respectively. The nursing reflection competency scores before and after the intervention were 57.00 ± 3.42 vs. 60.86 ± 0.95 in the intervention group and 59.63 ± 5.24 vs. 59.04 ± 0.89 in the control group. The teaching efficacy scores before and after the intervention were 157.04 ± 10.60 vs. 171.98 ± 2.54 in the intervention group and 161.59 ± 14.77 vs. 160.48 ± 2.46 in the control group.

Age, which was significantly different between the intervention and control groups, was treated as a covariate to conduct the ANCOVA. The changes in critical thinking disposition (F = 14.751, p < 0.001) and teaching efficacy (F = 11.047, p < 0.001) scores were significantly different between the two groups. However, there was no significant difference in the change in the nursing reflection competency (F = 2.674, p = 0.108) score between the two groups.

Reflective practice is crucial to clinical nurses’ professionalism. Reflective practice enables positive learning experiences through deep and meaningful learning, and is essential for integrating theory and practice. It also enables nurses to implement what they have learned into practice, understand their expertise, and develop clinical competencies [ 26 ]. In this respect, it is important for clinical nursing educators to have critical reflection competencies and promote experiential learning among new nurses. In this study, a critical reflection competency program was developed to enhance clinical nurse educators’ critical thinking and teaching competency.

This program was effective in improving critical thinking disposition. In interventions for critical reflection, various aspects, including the introduction of critical reflection and guidelines to promote critical reflection, such as small group discussions and feedback, can be considered [ 27 ]. The program reflected these aspects and helped improve participants’ critical thinking disposition. In the third and fourth sessions, synchronous discussions on sharing experiences of critical reflection were effective. This is consistent with previous studies in which discussions improved reflective competencies [ 21 , 28 ]. Therefore, sharing experiences in the discussion section should be a key element of future educational interventions for critical reflection competency.

Furthermore, the program was effective in improving teaching efficacy. Teaching efficacy is the instructor’s belief in one’s own ability to organize and implement teaching [ 29 ], and is closely related to age, clinical experience, educational experience, professional development, and teaching competency [ 30 – 32 ]. Nurses who are more clearly aware of their roles as instructors tend to exhibit higher confidence in their teaching abilities [ 33 , 34 ]. That is, the participants in this study were clearly aware of their roles and developed confidence by sharing their educational experiences about critical reflection.

However, the program did not have a significant effect on nursing reflection competencies. In a previous study [ 10 ], reflective practitioners (RPs) received four weeks of critical reflection training and trained new nurses for six months. During training, new nurses wrote critical reflective journals and RPs provided feedback and shared their experiences. In this study, it seems that the methods and frequency of using critical reflection in nursing education varied for each participant, resulting in insignificant results for nursing reflection competency. It is necessary to provide educational materials or guidelines so that nurse educators can use critical reflection in nursing education.

In this pilot study, the program was found to be effective in improving critical thinking disposition and teaching efficacy. The results show that the program can enhance the critical thinking disposition of nurse educators and help them develop teaching competency by critically reflecting on their educational experiences as instructors [ 35 , 36 ]. Therefore, various educational programs and training systems related to critical reflection are required [ 37 ]. However, many medical institutions find it difficult to provide sufficient educational support to nurses because of limited costs, time, and physical space [ 38 ]. Online real-time lectures and case-based discussions of the developed program can be useful alternatives to overcome barriers to nursing education support. Additionally, more effective educational content and platforms using e-learning can be developed based on the results of this study.

In this study, the critical reflection competency program for clinical nurse educators was developed and conducted. The program was an educational intervention to improve the critical reflection competency of clinical nurse educators in real time online. Several limitations must be considered when interpreting the present findings. The developed program did not affect nursing reflection competencies. Further, the post-test was conducted shortly after program completion. Therefore, there may be limitations to evaluating whether the developed program improves the quality of nursing education. In addition, the participants in this study were allocated regardless of their hospital’s characteristics. Considering variables such as the size of the hospitals, the number of new nurses, and the number of participants per hospital, it is necessary to assign nurse educators the intervention and control groups and to verify the effects of the program. Future studies should consider improving the study design to measure the long-term effects of the program and randomize the participants.