An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Common Barriers to Reporting Medical Errors

Salim aljabari, zuhal kadhim.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Academic Editor: Sylvia H. Hsu

Corresponding author.

Received 2021 Apr 19; Accepted 2021 Jun 3; Collection date 2021.

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Medical errors are the third leading cause of death in the United States. Reporting of all medical errors is important to better understand the problem and to implement solutions based on root causes. Underreporting of medical errors is a common and a challenging obstacle in the fight for patient safety. The goal of this study is to review common barriers to reporting medical errors.

We systematically reviewed the literature by searching the MEDLINE and SCOPUS databases for studies on barriers to reporting medical errors. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses guideline was followed in selecting eligible studies.

Thirty studies were included in the final review, 8 of which were from the United States. The majority of the studies used self-administered questionnaires (75%) to collect data. Nurses were the most studied providers (87%), followed by physicians (27%). Fear of consequences is the most reported barrier (63%), followed by lack of feedback (27%) and work climate/culture (27%). Barriers to reporting were highly variable between different centers.

1. Introduction

Medical errors (ME) are among the most important patient safety challenges facing hospitals and healthcare systems nowadays. Since the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report in 1999 “To Err is Human,” an increasing number of studies have shown how prevalent and deleterious ME are, especially in hospital medicine [ 1 ]. With this, healthcare leaders invested time and resources toward identifying and reducing ME [ 2 ].

A medical error is defined as “an incidence when there is an omission or commission in planning or execution that leads or could lead to unintended result” [ 3 ]. While the majority of ME do not lead to an apparent adverse effect, a significant number of patients either suffer a permanent injury or death from ME every year in the United States and around the world as a result of those errors [ 4 ].

Medical errors are the third leading cause of death in the United States after heart diseases and cancer [ 4 ]. It is estimated that more than 200,000 patients die annually in the United States from ME [ 5 ]. Furthermore, in addition to the harm inflicted on patients, medical errors are associated with an increased healthcare cost [ 6 ]. In a 2008 report, it was estimated that medical errors costed the healthcare system in the United States more than 17 billion dollars annually [ 7 , 8 ].

The first step in combating ME and improving patient safety is to study the different types of medical errors to better understand why medical errors happen. The causes, types, and rates of ME can vary from one institution to the other and change over time, especially as we implement changes in our healthcare delivery. Therefore, it is important to capture, track, and analyze all medical errors as possible at the institutional level [ 2 , 9 , 10 ].

As most of the nonmedication medical errors are hard to capture electronically and manual chart review is both cumbersome and time consuming, self-reporting is still the most reliable approach to capture ME [ 11 ]. Unfortunately, underreporting of ME is a commonly reported challenge even when healthcare institutions mandated reporting [ 12 ]. While there is no consensus on what defines “underreporting of ME,” it commonly refers to the lack of reports on significant ME events. The goal of this study is to review the reported perceived barriers to reporting medical errors by healthcare providers in hospital settings and to identify common themes.

Most of the reports on barriers to reporting ME are single centers; in this systematic review of the literature, we try to investigate whether the barriers to reporting ME varies from institution to the other or not and what common barriers are reported.

2. Methodology

We conducted a systemic review in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guideline [ 13 ].

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

We queried MEDLINE (2000–2020) and SCOPUS (2000–2020) databases for eligible studies. The year 2000 was chosen as the start date for eligibility as the vast of majority of publications regarding ME came after the IOM report in 1999 [ 1 ].

On MEDLLINE, a combination of the following search terms was used: (i) errors (medical subject heading (MeSH)), medication errors (MeSH) or near mess, and healthcare (MeSH), (ii) hospitals (MeSH), and (iii) disclosure (MeSH), “report$” (in the title), “ident$” (in the title), or “recog$” (in the title).

On Scopus, the following search string was used: (TITLE ((medica ∗ AND error) AND (report ∗ OR captur ∗ )) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBSTAGE, “final”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”))).

We manually removed duplicate studies, and we also evaluated additional eligible studies in the references of the final selected studies.

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

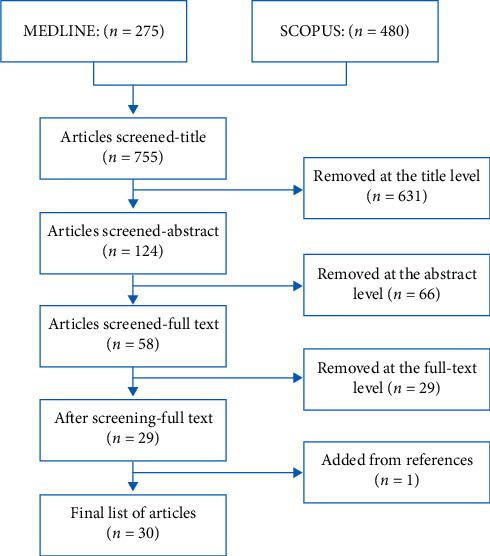

The returned studies were evaluated for proper content. Studies were screened for the following inclusion criteria: (i) English language, (ii) the focus of the research is to identify barriers to ME reporting, (iii) medical errors as defined above, not diagnostic errors or management errors, (iv) in hospital settings, and (v) full-text articles. The overview of the selection process is summarized in Figure 1 . The primary investigator screened the citations from the initial search using two-step approach. First, the titles and abstracts of all selected articles were screened for eligibility. Then, for the citations that considered relevant, the full-text we obtained was screened for eligibility.

The study selection process using the PRISMA guideline.

The following data elements were extracted from the final list of eligible studies: primary objective, study design, sample size, study setting, study subjects, country of the study, year of publication, recruitment of subjects, response rate in survey studies, pertinent results, primary outcomes, and limitations of the study.

The search yielded 755 studies of which 30 studies met the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 highlights the studies selection process. Table 1 is a brief summary of the included studies [ 14 – 43 ]. Eight of the selected studies were from the United States. The majority of the studies (74%) used self-administered questionnaires to identify perceived barriers for ME reporting. Three studies did post hoc analysis of national databases; those national databases were the results of self-administered questionnaires.

Summary of the selected studies.

As shown in Figure 2 , most of the included studies are relatively recent. Nurses were the most surveyed/studied healthcare providers, included in 26 (87%) included studies, followed by physicians (27%) and pharmacists (17%). Some of the studies (23%) recruited subjects from specific inpatient units, and the rest recruited subjects from all inpatient units. Eighteen of the included studies evaluated perceived barriers to reporting medication errors or medication administration errors, and the rest evaluated perceived barriers to reporting any medical error which included medication errors.

Year of publication of the selected studies.

3.1. Barriers to Reporting ME

We identified 7 common themes to the barriers reported in the included studies ( Table 2 ). We discuss the common themes in the following sections.

Common themes of barriers to reporting medical errors.

3.1.1. Fear of Consequences

Fear of consequences is the most reported factor for underreporting ME. 19 out of the 30 studies reported that fear is a significant barrier to report ME [ 14 – 16 , 20 – 22 , 25 , 37 – 40 , 42 ].

Fear of being blamed for the error is by far the most reported fear. But additionally, providers reported fear of losing one's job, fear of patient's or family's response to the ME, fear of being recognized as incompetent, fear of legal consequences, fear of punishment, and fear of losing respect by coworkers were also commonly reported [ 14 – 16 , 20 – 22 , 25 , 32 , 37 – 40 , 42 ].

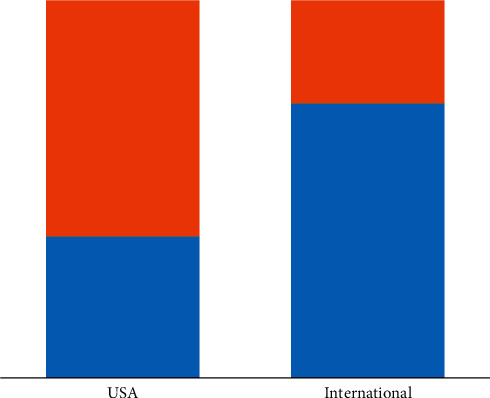

Not only is “fear of consequences” the most reported factor for underreporting, it also happens to be the most significant factor for underreporting in most of the included studies [ 14 – 16 , 20 – 22 , 25 , 32 , 37 – 40 , 42 ]. While fear of consequences might be more prominent in certain cultures than others and more prominent in hospitals with hierarchical structures [ 16 ], it has been reported at both local and international levels and in different management styles. Additionally, fear as a factor has not changed over the years. It is unclear whether an option to anonymously report ME would eliminate the fear barrier [ 14 – 16 , 20 – 22 , 25 , 32 , 37 – 40 , 42 ]. It does, however, seem that “fear of consequences” as a barrier to reporting is less prevalent in the United States compared to other countries ( Figure 3 ).

Percentage of studies where “fear of consequences” is an important barrier. Blue, yes, “fear of consequences” is an important barrier. Orange, no, “fear of consequences” is not an important barrier.

It is important to highlight that some of the included studies did not find “fear of consequences” as a significant factor for underreporting [ 41 ]. Findings from those studies suggest that we can overcome “fear of consequences” as a barrier.

3.1.2. Lack of Feedback

Both lack of feedback by administration and/or negative feedback have been associated with underreporting. While some studies reported the negative impact of improper feedback, some reported the positive impact of appropriate feedback. Specifically, it was evident that feedback to the reporting person about the error supports the provider who committed the error and communication openness regarding errors all improved reporting of ME [ 14 , 22 , 27 , 29 , 31 , 36 , 40 – 42 ].

3.1.3. Work Climate/Culture

The administration's attitude toward ME and the work environment are important factors that influence ME reporting [ 17 , 21 , 40 , 42 ]. It has been observed that when hospital administrators' responses to ME focus on the individuals, rather than the system, reporting rates of ME decrease [ 21 ]. Additionally, the lack of safety culture and error prevention programs is associated with underreporting [ 27 ]. On the other hand, work environments with a strong teamwork perception and psychological safety amongst employees are associated with better reporting of ME [ 30 , 32 ]. Work climate/culture issues as a barrier to reporting medical errors is the most reported barrier in studies from the United States ( Table 1 ).

3.1.4. Poor Understanding of ME and the Importance of Reporting ME

A number of studies reported poor understanding by providers as to what constitute a medical error as a barrier to reporting. Providers in a number of studies reported the lack of clear definition of medical errors and the lack of a clear protocol on what incidents need to be reported, as a significant barrier to reporting ME. Additionally, poor understanding of the importance of reporting ME is a significant barrier to reporting as well [ 21 , 23 , 35 , 38 , 41 , 44 ].

3.1.5. Time Consuming

Busy work schedule and high workload have been reported as significant factors for underreporting. Additionally, reporting itself is time consuming and cumbersome. Both forms of reporting systems (paper and electronic) are time consuming [ 20 , 23 , 25 , 38 , 41 , 44 ]. Physicians more than nurses reported time constrains as a barrier to reporting ME [ 41 ].

3.1.6. Lack of the Reporting System

It is no surprise that the lack of a reporting system is a barrier. Many studies, mostly international, reported the lack of a reporting system as a barrier to reporting [ 22 , 29 , 35 ]. A number of studies showed better reporting with electronic systems compared to paper reporting [ 45 ].

3.1.7. Personal Factors

A number of personal factors influence the reporting of ME. Younger and/or less experienced nurses are less likely to report ME. The longer the employment period is, the more likely it is for an employee to report ME. Additionally, personal experience with ME affected the rates of reporting medical errors [ 17 , 36 , 40 , 42 ].

4. Discussion

In this systematic review of literature, we present reported barriers to ME reporting in hospital setting. We identified and presented common themes to the reported barriers. We also highlighted the variation in perceived barriers between different centers and countries.

The healthcare system and healthcare delivery vary from one country to the other. Thus, it is no surprise that perceived barriers to reporting were also variable between different countries. For example, “fear of consequences” is more prevalent in East Asia and Middle East compared to the United States. On the other hand, work climate/culture is more reported as barrier in centers across the United States. Reported barriers also varied from one center to the other within the same country. These differences are probably secondary to different management strategies, reporting systems, different work place culture, and whether patient safety is a focus of the hospital administration or not.

Nurses, physicians, and pharmacists are the most studied groups of providers regarding ME and the reporting of ME. Unfortunately, none of the studies directly compared the barriers perceived by these different groups. It is logical to anticipate different perception of barriers between these groups of the provider. Additionally, current studies failed to include other groups of clinical providers such as respiratory therapists, physical/occupational therapists, and laboratory and radiology technicians, despite their significant role in hospital medicine.

Fear of consequences is reported in most of the studies we reviewed as one of the important barriers to reporting ME. Some of the sources for fear are modifiable, for example, fear of being blamed for the error or fear of losing one's job. Changing workplace culture and strategies in addressing reporting ME is an imperative step to overcome this barrier. A work culture that promotes patient safety, encourages error reporting, and implements system changes is essential. On the other hand, fear secondary to concern over patients' and their families' reactions to medical error is not modifiable or predictable. Educating the providers on the importance of ME disclosure to the patients/families and providing them with the necessary tools to better communicate ME and adverse events can help overcome some of these nonmodifiable fears.

The most challenging and probably most effective change to overcome barriers to reporting medical errors is the adoption of patient safety culture. Under patient safety culture, employees are rewarded and feel empowered to report and act on medical errors. This safety culture helps overcome the employee's fear of consequences and provides a work environment that is supportive of error recognition and reporting.

The reviewed studies showed that a significant number of healthcare providers lack proper understanding of what constitutes a medical error. Poor understanding of medical errors and the importance of reporting both lead to underreporting. Educating healthcare providers on what constitutes medical errors, the benefit of reporting medical errors even in the absence of apparent harm, and that medical error reports are used to identify system deficiencies rather than individual faults, can help improve ME reporting and eventually decrease ME.

As hospitals across the world are adopting changes in their management and care delivery to improve patient's safety, the barriers to reporting medical errors may change. Periodic evaluation of this matter is needed to continue the improvement process.

Healthcare institutions are encouraged to evaluate their ME reporting rates, perform root cause analysis for underreporting at the local level, and finally implement changes to improve reporting. The common themes we identified in this study can guide healthcare institutions in their local root cause analysis. Causes of ME and factors for underreporting ME may change with time as we implement changes to our healthcare delivery. Thus, continuous tracking of ME and periodic evaluation of the root causes is needed to continue the improvement process. In some institutions, deep changes in the hospital's management strategy to align with and encourage patient safety culture might be needed.

Our study has several limitations. The first limitation is inherent to the nature of survey and interview studies. All published reports on this matter used either self-administered questionnaires or interviews. The second limitation is inherent to the nature of systematic review of the literature. The variability of study methodology and study population makes it challenging to draw an objective conclusion. Due to the variability in the methodology and study population in the selected studies, a meta-analysis is not feasible and only a subjective conclusion can be presented.

5. Conclusion

We identified and presented 7 common themes of barriers to report medical errors. Fear of consequences is the most reported barrier worldwide, while work climate/culture is the most reported barrier in the United States. Barriers to reporting can vary from one center to the other. Each healthcare institution should identify local barriers to reporting and implement potential solutions. Overcoming the barriers may require changes in the hospital's management strategy to align with and encourage a patient safety culture. Further studies are needed to investigate whether an anonymous reporting system can help overcome the fear barrier and to compare perceived barriers to report ME between different healthcare providers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

- 1. Kohn L. T., Corrigan J., Donaldson M. S. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press (US); 2000. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Hoffmann B., Rohe J. Patient safety and error management. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2010;107(6):92–99. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0092. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Grober E. D., Bohnen J. M. Defining medical error. Canadian Journal of Surgery. Journal Canadien de Chirurgie. 2005;48(1):39–44. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Makary M. A., Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ Journal. 2016;353 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2139.i2139 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. James J. T. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. Journal of Patient Safety. 2013;9(3):122–128. doi: 10.1097/pts.0b013e3182948a69. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Andel C., Davidow S. L., Hollander M. D., Moreno D. A. Quality of care in the Korean health system. OECD Reviews of Health Care Quality: Korea 2012. 2012;39 1:39–75. doi: 10.1787/9789264173446-5-en. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Shreve J., Bos J.V. D., Gray T. K., Halford M. M., Rustagi K., Ziemkiewicz E. The economic measurement of medical errors sponsored by society of actuaries’ health section prepared by. Society of Actuaries’ Health Section. 2010 [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Bos J. V. D., Rustagi K., Gray T., Halford M., Ziemkiewicz E., Shreve J. The $17.1 billion problem: the annual cost of measurable medical errors. Health Affairs. 2011;30(4):596–603. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0084. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Wolf Z. R., Hughes R. G. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville, MD, USA: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. Error reporting and disclosure. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Kaldjian L. C., Jones E. W., Wu B. J., Forman-Hoffman V. L., Levi B. H., Rosenthal G. E. Reporting medical errors to improve patient SafetyA survey of physicians in teaching hospitals. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(1):40–46. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.12. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Classen D. C., Holmgren A. J., Co Z., et al. National trends in the safety performance of electronic health record systems from 2009 to 2018. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(5) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5547.e205547 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Morrison M., Cope V., Murray M. The underreporting of medication errors: a retrospective and comparative root cause analysis in an acute mental health unit over a 3-year period. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2018;27(6):1719–1728. doi: 10.1111/inm.12475. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G., PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.e1000097 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Mahdaviazad H., Askarian M., Kardeh B. Medical error reporting: status quo and perceived barriers in an orthopedic center in Iran. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2020;11:p. 14. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_235_18. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Dirik H. F., Samur M., Intepeler S. S., Hewison A. Nurses’ identification and reporting of medication errors. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2019;28(5-6):931–938. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14716. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Kim M. S., Kim C.-H. Canonical correlations between individual self-efficacy/organizational bottom-up approach and perceived barriers to reporting medication errors: a multicenter study. BMC Health Services Research. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4194-y. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Mousavi-Roknabadi R. S., Momennasab M., Askarian M., Haghshenas A., Marjadi B. Causes of medical errors and its under-reporting amongst pediatric nurses in Iran: a qualitative study. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2019;31(7):541–546. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzy202. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Rutledge D. N., Tina R., Gary O. Barriers to medication error reporting among hospital nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2018;27(9-10):1941–1949. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14335. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Stewart D., Thomas B., MacLure K., et al. Exploring facilitators and barriers to medication error reporting among healthcare professionals in qatar using the theoretical domains framework: a mixed-methods approach. PLoS One. 2018;13(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204987.e0204987 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Fathi A., Hajizadeh M., Moradi K., et al. Medication errors among nurses in teaching hospitals in the west of iran: what we need to know about prevalence, types, and barriers to reporting. Epidemiology and Health. 2017;39 doi: 10.4178/epih.e2017022.e2017022 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Hammoudi B. M., Yahya O. A. Factors associated with medication administration errors and why nurses fail to report them. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2017;32(3):1038–1046. doi: 10.1111/scs.12546. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Soydemir D., Intepeler S. S., Mert H. Barriers to medical error reporting for physicians and nurses. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2010;39(10):1348–1363. doi: 10.1177/0193945916671934. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Kang H.-J., Park H., Oh J. M., Lee E.-K. Perception of reporting medication errors including near-misses among Korean hospital pharmacists. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(39) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007795.e7795 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Mobarakabadi S. S., Ebrahimipour H., Najar A. V., Janghorban R., Azarkish F. Attitudes of mashhad public hospital’s nurses and midwives toward the causes and rates of medical errors reporting. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR. 2017;11 doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/23958.9349.QC04 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Farag A., Blegen M., Gedney-Lose A., Lose D., Perkhounkova Y. Voluntary medication error reporting by ED nurses: examining the association with work environment and social capital. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2017;43(3):246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2016.10.015. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Alqubaisi M., Tonna A., Strath A., Stewart D. Exploring behavioural determinants relating to health professional reporting of medication errors: a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2016;72(7):887–895. doi: 10.1007/s00228-016-2054-9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Patterson M. E., Pace H. A. A cross-sectional analysis investigating organizational factors that influence near-miss error reporting among hospital pharmacists. Journal of Patient Safety. 2016;12(2):114–117. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000125. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Yung H.-P., Yu S., Chu C., Hou I.-C., Tang F.-I. Nurses’ attitudes and perceived barriers to the reporting of medication administration errors. Journal of Nursing Management. 2016;24(5):580–588. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12360. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Poorolajal J., Rezaie S., Aghighi N. Barriers to medical error reporting. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;6:p. 97. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.166680. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Derickson R., Fishman J., Osatuke K., Teclaw R., Ramsel D. Psychological safety and error reporting within veterans health administration hospitals. Journal of Patient Safety. 2015;11(1):p. 7. doi: 10.1097/pts.0000000000000082. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Farag A. A., Anthony M. K. Examining the relationship among ambulatory surgical settings work environment, nurses’ characteristics, and medication errors reporting. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing. 2015;30(6):492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2014.11.014. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Jahromi Z. B., Parandavar N., Rahmanian S. Investigating factors associated with not reporting medical errors from the medical team’s point of view in jahrom, Iran. Global Journal of Health Science. 2014;6(6):p. 96. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v6n6p96. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Hwang J.-I., Ahn J. Teamwork and clinical error reporting among nurses in Korean hospitals. Asian Nursing Research. 2015;9(1):14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2014.09.002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Haw C., Stubbs J., Dickens G. L. Barriers to the reporting of medication administration errors and near misses: an interview study of nurses at a psychiatric hospital. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2014;21(9):797–805. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12143. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Mostafaei D., Barati Marnani A., Mosavi Esfahani H., et al. Medication errors of nurses and factors in refusal to report medication errors among nurses in a teaching medical center of Iran in 2012. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal. 2014;16(10) doi: 10.5812/ircmj.16600.e16600 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Patterson M. E., Pace H. A., Fincham J. E. Associations between communication climate and the frequency of medical error reporting among pharmacists within an inpatient setting. Journal of Patient Safety. 2013;9(3):129–133. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e318281edcb. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Aboshaiqah A. E. Barriers in reporting medication administration errors as perceived by nurses in Saudi Arabia. Middle East Journal of Scientific Research. 2013;17(2):130–136. doi: 10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2013.17.02.76110. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Hartnell N., MacKinnon N., Sketris I., Fleming M. Identifying, understanding and overcoming barriers to medication error reporting in hospitals: a focus group study. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2012;21(5):361–368. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000299. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Toruner E. K., Uysal G. Causes, reporting, and prevention of medication errors from a pediatric nurse perspective. The Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing: A Quarterly Publication of the Royal Australian Nursing Federation. 2012;29(4):28–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Chiang H.-Y., Lin S.-Y., Hsu S.-C., Ma S.-C. Factors determining hospital nurses’ failures in reporting medication errors in Taiwan. Nursing Outlook. 2010;58(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2009.06.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Kreckler S., Catchpole K., McCulloch P., Handa A. Factors influencing incident reporting in surgical care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(2):116–120. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.026534. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Chiang H.-Y., Pepper G. A. Barriers to nurses’ reporting of medication administration errors in Taiwan. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2006;38(4):392–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00133.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Ulanimo V. M. Nurse’s perceptions of causes of medication errors and barriers to reporting. Master’s Projects. 2005;822 doi: 10.31979/etd.nr6d-3nhy. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Uribe C. L., Schweikhart S. B., Pathak D. S., Studies E., Marsh G. B. Perceived barriers to medical-error reporting: an exploratory investigation. Journal of Healthcare Management. 2002;47(4):263–280. doi: 10.1097/00115514-200207000-00009. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Unal A., Seren İntepeler S. Medical error reporting software program development and its impact on pediatric units’ reporting medical errors. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020;36(2):10–15. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.2.732. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (481.2 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000.

To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

5 Error Reporting Systems

Although the previous chapter talked about creating and disseminating new knowledge to prevent errors from ever happening, this chapter looks at what happens after an error occurs and how to learn from errors and prevent their recurrence. One way to learn from errors is to establish a reporting system. Reporting systems have the potential to serve two important functions. They can hold providers accountable for performance or, alternatively, they can provide information that leads to improved safety. Conceptually, these purposes are not incompatible, but in reality, they can prove difficult to satisfy simultaneously.

Reporting systems whose primary purpose is to hold providers accountable are "mandatory reporting systems." Reporting focuses on errors associated with serious injuries or death. Most mandatory reporting systems are operated by state regulatory programs that have the authority to investigate specific cases and issue penalties or fines for wrong-doing. These systems serve three purposes. First, they provide the public with a minimum level of protection by assuring that the most serious errors are reported and investigated and appropriate follow-up action is taken. Second, they provide an incentive to health care organizations to improve patient safety in order to avoid the potential penalties and public exposure. Third, they require all health care organizations to make some level of investment in patient safety, thus creating a more level playing field. While safety experts recognize that errors resulting in serious harm are the "tip of the iceberg," they represent the small subset of errors that signal major system breakdowns with grave consequences for patients.

Reporting systems that focus on safety improvement are "voluntary reporting systems." The focus of voluntary systems is usually on errors that resulted in no harm (sometimes referred to as "near misses") or very minimal patient harm. Reports are usually submitted in confidence outside of the public arena and no penalties or fines are issued around a specific case. When voluntary systems focus on the analysis of ''near misses," their aim is to identify and remedy vulnerabilities in systems before the occurrence of harm. Voluntary reporting systems are particularly useful for identifying types of errors that occur too infrequently for an individual health care organization to readily detect based on their own data, and patterns of errors that point to systemic issues affecting all health care organizations.

The committee believes that there is a need for both mandatory and voluntary reporting systems and that they should be operated separately. Mandatory reporting systems should focus on detection of errors that result in serious patient harm or death (i.e., preventable adverse events). Adequate attention and resources must be devoted to analyzing reports and taking appropriate follow-up action to hold health care organizations accountable. The results of analyses of individual reports should be made available to the public.

The continued development of voluntary reporting efforts should also be encouraged. As discussed in Chapter 6 , reports submitted to voluntary reporting systems should be afforded legal protections from data discoverability. Health care organizations should be encouraged to participate in voluntary reporting systems as an important component of their patient safety programs.

For either type of reporting program, implementation without adequate resources for analysis and follow-up will not be useful. Receiving reports is only the first step in the process of reducing errors. Sufficient attention must be devoted to analyzing and understanding the causes of errors in order to make improvements.

- Recommendations

Recommendation 5.1 A nationwide mandatory reporting system should be established that provides for the collection of standardized information by state governments about adverse events that result in death or serious harm. Reporting should initially be required of hospitals and eventually be required of other institutional and ambulatory care delivery settings. Congress should

- designate the National Forum for Health Care Quality Measurement and Reporting as the entity responsible for promulgating and maintaining a core set of reporting standards to be used by states, including a nomenclature and taxonomy for reporting;

- require all health care organizations to report standardized information on a defined list of adverse events;

- provide funds and technical expertise for state governments to establish or adapt their current error reporting systems to collect the standardized information, analyze it and conduct follow-up action as needed with health care organizations. Should a state choose not to implement the mandatory reporting system, the Department of Health and Human Services should be designated as the responsible entity; and designate the Center for Patient Safety to:

convene states to share information and expertise, and to evaluate alternative approaches taken for implementing reporting programs, identify best practices for implementation, and assess the impact of state programs; and

receive and analyze aggregate reports from states to identify persistent safety issues that require more intensive analysis and/or a broader-based response (e.g., designing prototype systems or requesting a response by agencies, manufacturers or others).

Mandatory reporting systems should focus on the identification of serious adverse events attributable to error. Adverse events are deaths or serious injuries resulting from a medical intervention. 1 Not all, but many, adverse events result from errors. Mandatory reporting systems generally require health care organizations to submit reports on all serious adverse events for two reasons: they are easy to identify and hard to conceal. But it is only after careful analysis that the subset of reports of particular interest, namely those attributable to error, are identified and follow-up action can be taken.

The committee also believes that the focus of mandatory reporting system should be narrowly defined. There are significant costs associated with reporting systems, both costs to health care organizations and the cost of operating the oversight program. Furthermore, reporting is useful only if it includes analysis and follow-up of reported events. A more narrowly defined program has a better chance of being successful.

A standardized reporting format is needed to define what ought to be reported and how it should be reported. There are three purposes to having a standardized format. First, a standardized format permits data to be combined and tracked over time. Unless there are consistent definitions and methods for data collection across organizations, the data cannot be aggregated. Second, a standardized format lessens the burden on health care organizations that operate in multiple states or are subject to reporting requirements of multiple agencies and/or private oversight processes and group purchasers. Third, a standardized format facilitates communication with consumers and purchasers about patient safety.

The recently established National Forum for Health Care Quality Measurement and Reporting is well positioned to play a lead role in promulgating standardized reporting formats, including a nomenclature and taxonomy for reporting. The Forum is a public/private partnership charged with developing a comprehensive quality measurement and public reporting strategy. The existing reporting systems (i.e., national and state programs, public and private sector programs) also represent a growing body of expertise on how to collect and analyze information about errors, and should be consulted during this process. 2

Recommendation 5.2 The development of voluntary reporting efforts should be encouraged. The Center for Patient Safety should

- describe and disseminate information on existing voluntary reporting programs to encourage greater participation in them and track the development of new reporting systems as they form;

- convene sponsors and users of external reporting systems to evaluate what works and what does not work well in the programs, and ways to make them more effective;

- periodically assess whether additional efforts are needed to address gaps in information to improve patient safety and to encourage health care organizations to participate in voluntary reporting programs; and

- fund and evaluate pilot projects for reporting systems, both within individual health care organizations and collaborative efforts among health care organizations.

Voluntary reporting systems are an important part of an overall program for improving patient safety and should be encouraged. Accrediting bodies and group purchasers should recognize and reward health care organizations that participate in voluntary reporting systems.

The existing voluntary systems vary in scope, type of information collected, confidentiality provisions, how feedback to reporters is fashioned, and what is done with the information received in the reports. Although one of the voluntary medication error reporting systems has been in operation for 25 years, others have evolved in just the past six years. A concerted analysis should assess which features make the reporting system most useful, and how the systems can be made more effective and complementary.

The remainder of this chapter contains a discussion of existing error reporting systems, both within health care and other industries, and a discussion of the committee's recommendations.

- Review of Existing Reporting Systems in Health Care

There are a number of reporting systems in health care and other industries. The existing programs vary according to a number of design features. Some programs mandate reporting, whereas others are voluntary. Some programs receive reports from individuals, while others receive reports from organizations. The advantage of receiving reports from organizations is that it signifies that the institution has some commitment to making corrective system changes. The advantage of receiving reports from individuals is the opportunity for input from frontline practitioners. Reporting systems can also vary in their scope. Those that currently exist in health care tend to be more narrow in focus (e.g., medication-related error), but there are examples outside health care of very comprehensive systems.

There appear to be three general approaches taken in the existing reporting systems. One approach involves mandatory reporting to an external entity. This approach is typically employed by states that require reporting by health care organizations for purposes of accountability. A second approach is voluntary, confidential reporting to an external group for purposes of quality improvement (the first model may also use the information for quality improvement, but that is not its main purpose). There are medication reporting programs that fall into this category. Voluntary reporting systems are also used extensively in other industries such as aviation. The third approach is mandatory internal reporting with audit. For example, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires organizations to keep data internally according to a standardized format and to make the data available during on-site inspections. The data maintained internally are not routinely submitted, but may be submitted if the organization is selected in the sample of an annual survey.

The following sections provide an overview of existing health care reporting systems in these categories. They also include two examples from areas outside health care. The Aviation Safety Reporting System is discussed because it represents the most sophisticated and long-standing voluntary external reporting system. It differs from the voluntary external reporting systems in health care because of its comprehensive scope. Since there are currently no examples of mandatory internal reporting with audit, the characteristics of the OSHA approach are described.

Mandatory External Reporting

State adverse event tracking.

In a recent survey of states conducted by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), it was found that at least one-third of states have some form of adverse event reporting system. 3 It is likely that the actual percentage is higher because not all states responded to the survey and some of the nonrespondents may have reporting requirements. During the development of this report, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) interviewed 13 states with reporting systems to learn more about the scope and operation of their programs. The remainder of this section relates to information provided to the IOM. Appendix D summarizes selected characteristics of the reporting systems in these states, and includes information on what is reported to the state, who is required to submit reports, the number of reports received in the most recent year available, when the program began, who has access to the information collected and how the state uses the information that is obtained. This is not intended as a comprehensive review, but rather, as an overview of how some state reporting systems are designed.

States have generally focused their reporting systems on patient injuries or facility issues (e.g., fire, structural issues). Reports are submitted by health care organizations, mostly hospitals and/or nursing homes, although some states also include ambulatory care centers and other licensed facilities. Although the programs may require reporting from a variety of licensed facilities, nursing homes often consume a great deal of state regulatory attention. In Connecticut, 14,000 of almost 15,000 reports received in 1996 were from nursing homes.

Several of the programs have been in place for ten years or longer, although they have undergone revisions since their inception. For example, New York State's program has been in place since 1985, but it has been reworked three times, the most recent version having been implemented in 1998 after a three-year pilot test.

Underreporting is believed to plague all programs, especially in their early years of operation. Colorado's program received 17 reports in its first two years of operation, 4 but ten years later, received more than 1000 reports. On the other hand, New York's program receives approximately 20,000 reports annually.

The state programs reported that they protected the confidentiality of certain data, but policies varied. Patient identifiers were never released; practitioner's identity was rarely available. States varied in whether or not the hospital's name was released. For example, Florida is barred from releasing any information with hospital or patient identification; it releases only a statewide summary.

The submission of a report itself did not trigger any public release of information. Some states posted information on the Internet, but only after the health department took official action against the facility. New York has plans to release hospital-specific aggregate information (e.g., how many reports were submitted), but no information on any specific report.

Few states aggregate the data or analyze them to identify general trends. For the most part, analysis and follow-up occurs on a case-by-case basis. For example, in some states, the report alerted the health department to a problem; the department would assess whether or not to conduct a follow-up inspection of the facility, If an inspection was conducted, the department might require corrective action and/or issue a deficiency notice for review during application for relicensure.

Two major impediments to making greater use of the reported data were identified: lack of resources and limitations in data. Many states cited a lack of resources as a reason for conducting only limited analysis of data. Several states had, or were planning to construct a database so that information could be tracked over time but had difficulty getting the resources or expertise to do so. Additionally, several states indicated that the information they received in reports from health care organizations was inadequate and variable. The need for more standardized reporting formats was noted.

A focus group was convened with representatives from approximately 20 states at the 12th Annual conference of the National Academy of State Health Policy (August 2, 1999). This discussion reinforced the concerns heard in IOM's telephone interviews. Resource constraints were identified, as well as the need for tools, methods, and protocols to constructively address the issue. The group also identified the need for mechanisms to improve the flow of information between the state, consumers, and providers to encourage safety and quality improvements. The need for collaboration across states to identify and promote best practices was also highlighted. Finally, the group emphasized the need to create greater awareness of the problem of patient safety and errors in health care among the general public and among health care professionals as well.

In summary, the state programs appear to provide a public response for investigation of specific events, 5 but are less successful in synthesizing information to analyze where broad system improvements might take place or in communicating alerts and concerns to other institutions. Resource constraints and, in some cases, poorly specified reporting requirements contribute to the inability to have as great an impact as desired.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

Reports submitted to FDA are one part of the surveillance system for monitoring adverse events associated with medical products after their approval (referred to as postmarketing surveillance). 6 Reports may be submitted directly to FDA or through MedWatch, FDA's reporting program. For medical devices, manufacturers are required to report deaths, serious injuries, and malfunctions to FDA. User facilities (hospitals, nursing homes) are required to report deaths to the manufacturer and FDA and to report serious injuries to the manufacturer. For suspected adverse events associated with drugs, reporting is mandatory for manufacturers and voluntary for physicians, consumers, and others. FDA activities are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 7 .

Voluntary External Reporting

Joint commission on accreditation of healthcare organizations (jcaho).

JCAHO initiated a sentinel event reporting system for hospitals in 1996 (see Chapter 7 for a discussion on JCAHO activities related to accreditation). For its program, a sentinel event is defined as an "unexpected occurrence or variation involving death or serious physical or psychological injury or the risk thereof." Sentinel events subject to reporting are those that have resulted in an unanticipated death or major permanent loss of function not related to the natural course of the patient's illness or underlying condition, or an event that meets one of the following criteria (even if the outcome was not death or major permanent loss of function): suicide of a patient in a setting where the patient receives around-the-clock care; infant abduction or discharge to the wrong facility; rape; hemolytic transfusion reaction involving administration of blood or blood products having major blood group incompatibilities; or surgery on the wrong patient or wrong body part. 7

The Joint Commission requires that an organization experiencing a sentinel event conduct a root cause analysis, a process for identifying the basic or causal factors of the event. A hospital may voluntarily report an incident to JCAHO and submit their root cause analysis (including actions for improvement). If an organization experiences a sentinel event but does not voluntarily report it and JCAHO discovers the event (e.g., from the media, patient report, employee report), the organization is still required to prepare an acceptable root cause analysis and action plan. If the root cause analysis and action plan are not acceptable, the organization may be placed on accreditation watch until an acceptable plan is prepared. Root cause analyses and action plans are confidential; they are destroyed after required data elements have been entered into a JCAHO database to be used for tracking and sharing risk reduction strategies.

JCAHO encountered some resistance from hospitals when it introduced the sentinel event reporting program and is still working through the issues today. Since the initiation of the program in 1996, JCAHO has changed the definition of a sentinel event to add more detail, instituted procedural revisions on reporting, authorized on-site review of root cause analyses to minimize risk of additional liability exposure, and altered the procedures for affecting a facility's accreditation status (and disclosing this change to the public) while an event is being investigated. 8 However, concerns remain regarding the confidentiality of data reported to JCAHO and the extent to which the information on a sentinel event is no longer protected under peer review if it is shared with JCAHO (these issues are discussed in Chapter 6 ).

There is the potential for cooperation between the JCAHO sentinel event program and state adverse event tracking programs. For example, JCAHO is currently working with New York State so that hospitals that report to the state's program are considered to be in compliance with JCAHO's sentinel events program. 9 This will reduce the need for hospitals to report to multiple groups with different requirements for each. The state and JCAHO are also seeking to improve communications between the two organizations before and after hospitals are surveyed for accreditation.

Medication Errors Reporting (MER) Program

The MER program is a voluntary medication error reporting system originated by the Institute for Safe Medication Practice (ISMP) in 1975 and administered today by U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP). The MER program receives reports from frontline practitioners via mail, telephone, or the Internet. Information is also shared with the FDA and the pharmaceutical companies mentioned in the reports. ISMP also publishes error reports received from USP in 16 publications every month and produces a biweekly publication and periodic special alerts that go to all hospitals in the United States. The MER program has received approximately 3,000 reports since 1993, primarily identifying new and emerging problems based on reports from people on the frontline.

MedMARx from the U.S. Pharmacopoeia

In August 1998, U.S. Pharmacopeia initiated the MedMARx program, an Internet-based, anonymous, voluntary system for hospitals to report medication errors. Hospitals subscribe to the program. Hospital employees may then report a medication error anonymously to MedMARx by completing a standardized report. Hospital management is then able to retrieve compiled data on its own facility and also obtain nonidentified comparative information on other participating hospitals. All information reported to MedMARx remains anonymous. All data and correspondence are tied to a confidential facility identification number. Information is not shared with FDA at this time. The JCAHO framework for conducting a root cause analysis is on the system for the convenience of reporters to download the forms, but the programs are not integrated.

Aviation Safety Reporting System at NASA

The three voluntary reporting systems described above represent focused initiatives that apply to a particular type of organization (e.g., hospital) or particular type of error (e.g., medication error). The Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) is a voluntary, confidential incident reporting system used to identify hazards and latent system deficiencies in order to eliminate or mitigate them. 10 ASRS is described as an example of a comprehensive voluntary reporting system.

ASRS receives "incident" reports, defined as an occurrence associated with the operation of an aircraft that affects or could affect the safety of operations. Reports into ASRS are submitted by individuals confidentially. After any additional information is obtained through follow-up with reporters, the information is maintained anonymously in a database (reports submitted anonymously are not accepted). ASRS is designed to capture near misses, which are seen as fruitful areas for designing solutions to prevent future accidents.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigates aviation accidents. An "accident" is defined as an occurrence that results in death or serious injury or in which the aircraft receives substantial damage. NTSB was formed in 1967 and ASRS in 1976. The investigation of accidents thus preceded attention to near misses.

ASRS operates independently from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). It was originally formed under FAA, but operations were shifted to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) because of the reluctance of pilots to report incidents (as differentiated from accidents) to a regulatory authority. FAA funds the ASRS, but NASA administers and manages the program independently. ASRS has no regulatory or enforcement powers over civil aviation.

ASRS issues alerts to the industry on hazards it identifies as needed (e.g., ASRS does not go through a regulatory agency to issue an alert or other communication; Linda Connell, Director of ASRS, personal communication, May 20, 1999). If a situation is very serious, it may issue an alert after only one incident. Often, ASRS has received multiple reports and noted a pattern. The purpose of ASRS alerts and other communications is to notify others of problems. Alerts may be disseminated throughout the industry and may also be communicated to the FAA to notify them about areas that may require action. ASRS does not propose or advocate specific solutions because it believes this would interfere with its role as an "honest broker" for reporters. As a result, although some reported problems may be acted upon, others are not. For example, ASRS has been notifying FAA and the industry about problems that have persisted throughout its 23-year history, such as problems with call signs. To date, no agency has been able to a find permanent solution. However, ASRS continues to issue alerts about the problem to remind people that the problem has not been solved.

ASRS maintains a database on reported incidents, identifies hazards and patterns in the data, conducts analyses on types of incidents, and interviews reporters when indicated. It sends out alert messages, publishes a monthly safety bulletin that is distributed to 85,000 readers and produces a semiannual safety topics publication targeted to the operators and flight crews of complex aircraft. Quick-response studies may be conducted for NTSB and FAA as needed (e.g., if an accident occurred, they may look for similar incidents). ASRS receives over 30,000 reports annually and has an operating budget of approximately $2 million. 11

A more recent program is the Aviation Safety Action Programs. The de-identification of reports submitted to ASRS means that organizations do not have access to reports that identify problems in their own operations. In 1997, FAA established a demonstration program for the creation of Aviation Safety Action Programs (ASAP). 12 Under ASAP, an employee may submit a report on a serious incident that does not meet the threshold of an accident to the airline and the FAA with pilot and flight identification. Reports are reviewed at a regular meeting of an event review committee that includes representatives from the employee group, FAA and the airline. Corrective actions are identified as needed.

Mandatory Internal Reporting with Audit

Occupational safety and health administration.

OSHA uses a different approach for reporting than the systems already described. It requires companies to keep internal records of injury and illness, but does not require that the data be routinely submitted. The records must be made available during on-site inspections and may be required if the company is included in an annual survey of a sample of companies. 13 OSHA and the Bureau of Labor Statistics both conduct sample surveys and collect the routine data maintained by the companies. These agencies conduct surveys to construct incidence rates on worksite illness and injury that are tracked over time or to examine particular issues of concern, such as a certain activity.

Employers with 11 or more employees must routinely maintain records of occupational injury and illness as they occur. Employees have access to a summary log of the injury and illness reports, and to copies of any citations issued by OSHA. Citations must be posted for three days or until the problem is corrected, whichever is longer. Companies with ten or fewer employers are exempt from keeping such records unless they are selected for an annual survey and are required to report for that period. Some industries, although required to comply with OSHA rules, are not subject to record-keeping requirements (including some retail, trade, insurance, real estate, and services). However, they must still report the most serious accidents (defined as an accident that results in at least one death or five or more hospitalizations).

Key Points from Existing Reporting Systems

There are a number of ways that reporting systems can contribute to improving patient safety. Good reporting systems are a tool for gathering sufficient information about errors from multiple reporters to try to understand the factors that contribute to them and subsequently prevent their recurrence throughout the health care system. Feedback and dissemination of information can create an awareness of problems that have been encountered elsewhere and an expectation that errors should be fixed and safety is important. Finally, a larger-scale effort may improve analytic power by increasing the number of ''rare" events reported. A serious error may not occur frequently enough in a single entity to be detected as a systematic problem; it is perceived as a random occurrence. On a larger scale, a trend may be easier to detect.

Reporting systems are particularly useful in their ability to detect unusual events or emerging problems. 14 Unusual events are easier to detect and report because they are rare, whereas common events are viewed as part of the "normal" course. For example, a poorly designed medical device that malfunctions routinely becomes viewed as a normal risk and one that practitioners typically find ways to work around. Some common errors may be recognized and reported, but many are not. Reporting systems also potentially allow for a fast response to a problem since reports come in spontaneously as an event occurs and can be reacted to quickly.

Two challenges that confront reporting systems are getting sufficient participation in the programs and building an adequate response system. All reporting programs, whether mandatory or voluntary, are perceived to suffer from underreporting. Indeed, some experts assert that all reporting is fundamentally voluntary since even mandated reporting can be avoided. 15 However, some mandatory programs receive many reports and some voluntary programs receive fewer reports. New York's mandatory program receives an average of 20,000 reports annually, while a leading voluntary program, the MER Program, has received approximately 3,000 reports since 1993. Reporting adverse reactions to medications to FDA is voluntary for practitioners, and they are not subject to FDA regulation (so the report is not going to an authority that can take action against them). Yet, underreporting is still perceived. 16 Of the approximately 235,000 reports received annually at FDA, 90 percent come from manufacturers (although practitioners may report to the manufacturers who report to FDA). Only about 10 percent are reported directly through MedWatch, mainly from practitioners.

The volume of reporting is influenced by more factors than simply whether reporting is mandatory or voluntary. Several reasons have been suggested for underreporting. One factor is related to confidentiality. As already described, many of the states contacted faced concerns about confidentiality, and what information should be released and when. Although patients were never identified, states varied on whether to release the identity of organizations. They were faced with having to balance the concerns of health care organizations to encourage participation in the program and the importance of making information available to protect and inform consumers. Voluntary programs often set up special procedures to protect the confidentiality of the information they receive. The issue of data protection and discoverability is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 6 .

Another set of factors that affects the volume of reports relates to reporter perceptions and abilities. Feedback to reporters is believed to influence participation levels. 17 Belief by reporters that the information is actually used assures them that the time taken to file a report is worthwhile. Reporters need to perceive a benefit for reporting. This is true for all reporting systems, whether mandatory or voluntary. Health care organizations that are trained and educated in event recognition are also more likely to report events. 18 Clear standards, definitions, and tools are also believed to influence reporting levels. Clarity and ease helps reporters know what is expected to be reported and when. One experiment tried paying for reporting. This increased reporting while payments were provided, but the volume was not sustained after payments stopped. 19

Although some reporting systems that focus on adverse events, such as hospital patients experiencing nosocomial infections, are used to develop incidence rates and track changes in these rates over time, caution must be exercised when calculating rates from adverse event reporting systems for several reasons. Many reporting systems are considered to be "passive" in that they rely on a report being submitted by someone who has observed the event. 20 "Active" systems work with participating health care organizations to collect complete data on an issue being tracked to determine rates of an adverse event 21 (e.g., the CDC conducted an active surveillance study of vaccine events with four HMOs linking vaccination records with hospital admission records 22 ).

The low occurrence of serious errors can also produce wide variations in frequency from year to year. Some organizations and individuals may routinely report more than others, either because they are more safety conscious or because they have better internal systems. 23 Certain characteristics of medical processes may make it difficult to identify an adverse event, which can also lead to variation in reporting. For example, adverse drug events are difficult to detect when they are widely separated in time from the original use of the drug or when the reaction occurs commonly in an unexposed population. 24 These reasons make it difficult to develop reliable rates from reporting systems, although it may be possible to do so in selected cases. However, even without a rate, repetitive reports flag areas of concern that require attention.

It is important to note, however, that the goal of reporting programs is not to count the number of reports. The volume of reports by itself does not indicate the success of a program. Analyzing and using the information they provide and attaching the right tools, expertise and resources to the information contained in the reports helps to correct errors. Medication errors are heavily monitored, by several public and private reporting systems, some of which afford anonymous reporting. It is possible for a practitioner to voluntarily and confidentially report a medication error to the FDA or to private systems (e.g., MER program, MedMARx). Some states with mandatory reporting may also receive reports of medication-related adverse events. Yet, some medication problems continue to occur, such as unexpected deaths from the availability of concentrated potassium chloride on patient care units. 25

Reporting systems without adequate resources for analysis and follow-up action are not useful. Reporting without analysis or follow-up may even be counterproductive in that it weakens support for constructive responses and is viewed as a waste of resources. Although exact figures are not available, it is generally believed that the analysis of reports is harder to do, takes longer and costs more than data collection. Being able to conduct good analyses also requires that the information received through reporting systems is adequate. People involved in the operation of reporting systems believe it is better to have good information on fewer cases than poor information on many cases. The perceived value of reports (in any type of reporting system) lies in the narrative that describes the event and the circumstances under which it occurred. Inadequate information provides no benefit to the reporter or the health system.

- Discussion of Committee Recommendations

Reporting systems may have a primary focus on accountability or on safety improvement. Design features vary depending on the primary purpose. Accountability systems are mandatory and usually receive reports on errors that resulted in serious harm or death; safety improvement systems are generally voluntary and often receive reports on events resulting in less serious harm or no harm at all. Accountability systems tend to receive reports from organizations; safety improvement systems may receive reports from organizations or frontline practitioners. Accountability systems may release information to the public; safety improvement systems are more likely to be confidential.

Figure 5.1 presents a proposed hierarchy of reporting, sorting potential errors into two categories: (1) errors that result in serious injury or death (i.e., serious preventable adverse events), and (2) lesser injuries or noninjurious events (near-misses). 26 Few errors cause serious harm or death; that is the tip of the triangle. Most errors result in less or no harm, but may represent early warning signs of a system failure with the potential to cause serious harm or death.

Figure 5–1

Hierarchy of reporting.

The committee believes that the focus of mandatory reporting systems should be on the top tier of the triangle in Figure 5.1 . Errors in the lower tier are issues that might be the focus of voluntary external reporting systems, as well as research projects supported by the Center for Patient Safety and internal patient safety programs of health care organizations. The core reporting formats and measures promulgated by the National Forum for Health Care Quality Measurement and Reporting should focus first on the top tier. Additional standardized formats and measures pertaining to other types of errors might be promulgated in the future to serve as tools to be made available to voluntary reporting systems or health care organizations for quality improvement purposes.

The committee believes there is an important role for both mandatory and voluntary reporting systems. Mandatory reporting of serious adverse events is essential for public accountability and the current practices are too lax, both in enforcement of the requirements for reporting and in the regulatory responses to these reports. The public has the right to expect health care organizations to respond to evidence of safety hazards by taking whatever steps are necessary to make it difficult or impossible for a similar event to occur in the future. The public also has the right to be informed about unsafe conditions. Requests by providers for confidentiality and protection from liability seem inappropriate in this context. At the same time, the committee recognizes that appropriately designed voluntary reporting systems have the potential to yield information that will impact significantly on patient safety and can be widely disseminated. The reports and analyses in these reporting systems should be protected from disclosure for legal liability purposes.

Mandatory Reporting of Serious Adverse Events

The committee believes there should be a mandatory reporting program for serious adverse events, implemented nationwide, linked to systems of accountability, and made available to the public. Comparable to aviation "accidents" that are investigated by the National Transportation Safety Board, health care organizations should be required to submit reports on the most serious adverse events using a standard format. The types of adverse events to be reported may include, for example, maternal deaths; deaths or serious injuries associated with the use of a new device, operation or medication; deaths following elective surgery or anesthetic deaths in Class I patients. In light of the sizable number of states that have already established mandatory reporting systems, the committee thinks it would be wise to build on this experience in creating a standardized reporting system that is implemented nationwide.

Within these objectives, however, there should be flexibility in implementation. Flexibility and innovation are important in this stage of development because the existing state programs have used different approaches to implement their programs and a "best practice" or preferred approach is not yet known. The Center for Patient Safety can support states in identifying and communicating best practices. States could choose to collect and analyze such data themselves. Alternatively, they could rely on an accrediting body, such as Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations or the National Committee for Quality Assurance, to perform the function for them as many states do now for licensing surveys. States could also contract with peer review organizations (PROs) to perform the function. As noted in Chapter 4, the Center for Patient Safety should evaluate the approaches taken by states in implementing reporting programs. States have employed a variety of strategies in their programs, yet few (if any) have been subject to rigorous evaluation. Program features that might be evaluated include: factors that encourage or inhibit reporting, methods of analyzing reports, roles and responsibilities of health care organizations and the state in investigating adverse events, follow-up actions taken by states, information disclosed to the public, and uses of the information by consumers and purchasers.

Although states should have flexibility in how they choose to implement the reporting program, all state programs should require reporting for a standardized core set of adverse events that result in death or serious injury, and the information reported should also be standardized.

The committee believes that these standardized reporting formats should be developed by an organization with the following characteristics. First, it should be a public-private partnership, to reflect the need for involvement by both sectors and the potential use of the reporting format by both the public and the private sectors. Second, it should be broadly representative, to reflect the input from many different stakeholders that have an interest in patient safety. Third, it should be able to gather the expertise needed for the task. This requires adequate financial resources, as well as sufficient standing to involve the leading experts. Enabling legislation can support all three objectives.

The National Forum for Health Care Quality Measurement and Reporting meets these criteria. The purpose of this public-private partnership (formed in May 1999) is to develop a comprehensive quality measurement and public reporting strategy that addresses priorities for quality measurement for all stakeholders consistent with national aims for quality improvement in health care. It is to develop a plan for implementing quality measurement, data collection and reporting standards; identify core sets of measures; and promote standardized measurement specifications. One of its specific tasks should relate to patient safety.

The advantage of using the Forum is that its goal already is to develop a measurement framework for quality generally. A focus on safety would ensure that safety gets built into a broader quality agenda. A public-private partnership would also be able to convene the mix of stakeholders who, it is hoped, would subsequently adopt the standards and standardized reporting recommendations of the Forum. However, the Forum is a new organization that is just starting to come together; undoubtedly some time will be required to build the organization and set its agenda.

Federal enabling legislation and support will be required to direct the National Forum for Health Care Quality Measurement and Reporting to promulgate standardized reporting requirements for serious adverse events and encourage all states to implement the minimum reporting requirements. Such federal legislation pertaining to state roles may be modeled after the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). HIPAA provides three options for implementing a program: (1) states may pass laws congruent with or stronger than the federal floor and enforce them using state agencies; (2) they may create an acceptable alternative mechanism and enforce it with state agencies; or finally, (3) they may decline to pass new laws or modify existing ones and leave enforcement of HIPAA to the federal government. 27 OSHA is similarly designed in that states may develop their own OSHA program with matching funds from the federal government; the federal OSHA program is employed in states that have not formed a state-level program.

Voluntary Reporting Systems

The committee believes that voluntary reporting systems play a valuable role in encouraging improvements in patient safety and are a complement to mandatory reporting systems. The committee considered whether a national voluntary reporting system should be established similar to the Aviation Safety Reporting System. Compared to mandatory reporting, voluntary reporting systems usually receive reports from frontline practitioners who can report hazardous conditions that may or may not have resulted in patient harm. The aim is to learn about these potential precursors to errors and try to prevent a tragedy from occurring.