Research Hypothesis In Psychology: Types, & Examples

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A research hypothesis, in its plural form “hypotheses,” is a specific, testable prediction about the anticipated results of a study, established at its outset. It is a key component of the scientific method .

Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding

Some key points about hypotheses:

- A hypothesis expresses an expected pattern or relationship. It connects the variables under investigation.

- It is stated in clear, precise terms before any data collection or analysis occurs. This makes the hypothesis testable.

- A hypothesis must be falsifiable. It should be possible, even if unlikely in practice, to collect data that disconfirms rather than supports the hypothesis.

- Hypotheses guide research. Scientists design studies to explicitly evaluate hypotheses about how nature works.

- For a hypothesis to be valid, it must be testable against empirical evidence. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

- Hypotheses are informed by background knowledge and observation, but go beyond what is already known to propose an explanation of how or why something occurs.

Predictions typically arise from a thorough knowledge of the research literature, curiosity about real-world problems or implications, and integrating this to advance theory. They build on existing literature while providing new insight.

Types of Research Hypotheses

Alternative hypothesis.

The research hypothesis is often called the alternative or experimental hypothesis in experimental research.

It typically suggests a potential relationship between two key variables: the independent variable, which the researcher manipulates, and the dependent variable, which is measured based on those changes.

The alternative hypothesis states a relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable affects the other).

A hypothesis is a testable statement or prediction about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a key component of the scientific method. Some key points about hypotheses:

- Important hypotheses lead to predictions that can be tested empirically. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

In summary, a hypothesis is a precise, testable statement of what researchers expect to happen in a study and why. Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding.

An experimental hypothesis predicts what change(s) will occur in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated.

It states that the results are not due to chance and are significant in supporting the theory being investigated.

The alternative hypothesis can be directional, indicating a specific direction of the effect, or non-directional, suggesting a difference without specifying its nature. It’s what researchers aim to support or demonstrate through their study.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states no relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable does not affect the other). There will be no changes in the dependent variable due to manipulating the independent variable.

It states results are due to chance and are not significant in supporting the idea being investigated.

The null hypothesis, positing no effect or relationship, is a foundational contrast to the research hypothesis in scientific inquiry. It establishes a baseline for statistical testing, promoting objectivity by initiating research from a neutral stance.

Many statistical methods are tailored to test the null hypothesis, determining the likelihood of observed results if no true effect exists.

This dual-hypothesis approach provides clarity, ensuring that research intentions are explicit, and fosters consistency across scientific studies, enhancing the standardization and interpretability of research outcomes.

Nondirectional Hypothesis

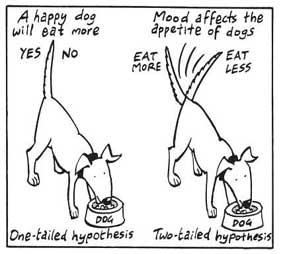

A non-directional hypothesis, also known as a two-tailed hypothesis, predicts that there is a difference or relationship between two variables but does not specify the direction of this relationship.

It merely indicates that a change or effect will occur without predicting which group will have higher or lower values.

For example, “There is a difference in performance between Group A and Group B” is a non-directional hypothesis.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional (one-tailed) hypothesis predicts the nature of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. It predicts in which direction the change will take place. (i.e., greater, smaller, less, more)

It specifies whether one variable is greater, lesser, or different from another, rather than just indicating that there’s a difference without specifying its nature.

For example, “Exercise increases weight loss” is a directional hypothesis.

Falsifiability

The Falsification Principle, proposed by Karl Popper , is a way of demarcating science from non-science. It suggests that for a theory or hypothesis to be considered scientific, it must be testable and irrefutable.

Falsifiability emphasizes that scientific claims shouldn’t just be confirmable but should also have the potential to be proven wrong.

It means that there should exist some potential evidence or experiment that could prove the proposition false.

However many confirming instances exist for a theory, it only takes one counter observation to falsify it. For example, the hypothesis that “all swans are white,” can be falsified by observing a black swan.

For Popper, science should attempt to disprove a theory rather than attempt to continually provide evidence to support a research hypothesis.

Can a Hypothesis be Proven?

Hypotheses make probabilistic predictions. They state the expected outcome if a particular relationship exists. However, a study result supporting a hypothesis does not definitively prove it is true.

All studies have limitations. There may be unknown confounding factors or issues that limit the certainty of conclusions. Additional studies may yield different results.

In science, hypotheses can realistically only be supported with some degree of confidence, not proven. The process of science is to incrementally accumulate evidence for and against hypothesized relationships in an ongoing pursuit of better models and explanations that best fit the empirical data. But hypotheses remain open to revision and rejection if that is where the evidence leads.

- Disproving a hypothesis is definitive. Solid disconfirmatory evidence will falsify a hypothesis and require altering or discarding it based on the evidence.

- However, confirming evidence is always open to revision. Other explanations may account for the same results, and additional or contradictory evidence may emerge over time.

We can never 100% prove the alternative hypothesis. Instead, we see if we can disprove, or reject the null hypothesis.

If we reject the null hypothesis, this doesn’t mean that our alternative hypothesis is correct but does support the alternative/experimental hypothesis.

Upon analysis of the results, an alternative hypothesis can be rejected or supported, but it can never be proven to be correct. We must avoid any reference to results proving a theory as this implies 100% certainty, and there is always a chance that evidence may exist which could refute a theory.

How to Write a Hypothesis

- Identify variables . The researcher manipulates the independent variable and the dependent variable is the measured outcome.

- Operationalized the variables being investigated . Operationalization of a hypothesis refers to the process of making the variables physically measurable or testable, e.g. if you are about to study aggression, you might count the number of punches given by participants.

- Decide on a direction for your prediction . If there is evidence in the literature to support a specific effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a directional (one-tailed) hypothesis. If there are limited or ambiguous findings in the literature regarding the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis.

- Make it Testable : Ensure your hypothesis can be tested through experimentation or observation. It should be possible to prove it false (principle of falsifiability).

- Clear & concise language . A strong hypothesis is concise (typically one to two sentences long), and formulated using clear and straightforward language, ensuring it’s easily understood and testable.

Consider a hypothesis many teachers might subscribe to: students work better on Monday morning than on Friday afternoon (IV=Day, DV= Standard of work).

Now, if we decide to study this by giving the same group of students a lesson on a Monday morning and a Friday afternoon and then measuring their immediate recall of the material covered in each session, we would end up with the following:

- The alternative hypothesis states that students will recall significantly more information on a Monday morning than on a Friday afternoon.

- The null hypothesis states that there will be no significant difference in the amount recalled on a Monday morning compared to a Friday afternoon. Any difference will be due to chance or confounding factors.

More Examples

- Memory : Participants exposed to classical music during study sessions will recall more items from a list than those who studied in silence.

- Social Psychology : Individuals who frequently engage in social media use will report higher levels of perceived social isolation compared to those who use it infrequently.

- Developmental Psychology : Children who engage in regular imaginative play have better problem-solving skills than those who don’t.

- Clinical Psychology : Cognitive-behavioral therapy will be more effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety over a 6-month period compared to traditional talk therapy.

- Cognitive Psychology : Individuals who multitask between various electronic devices will have shorter attention spans on focused tasks than those who single-task.

- Health Psychology : Patients who practice mindfulness meditation will experience lower levels of chronic pain compared to those who don’t meditate.

- Organizational Psychology : Employees in open-plan offices will report higher levels of stress than those in private offices.

- Behavioral Psychology : Rats rewarded with food after pressing a lever will press it more frequently than rats who receive no reward.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

6 Hypothesis Examples in Psychology

The hypothesis is one of the most important steps of psychological research. Hypothesis refers to an assumption or the temporary statement made by the researcher before the execution of the experiment, regarding the possible outcome of that experiment. A hypothesis can be tested through various scientific and statistical tools. It is a logical guess based on previous knowledge and investigations related to the problem under investigation. In this article, we’ll learn about the significance of the hypothesis, the sources of the hypothesis, and the various examples of the hypothesis.

Sources of Hypothesis

The formulation of a good hypothesis is not an easy task. One needs to take care of the various crucial steps to get an accurate hypothesis. The hypothesis formulation demands both the creativity of the researcher and his/her years of experience. The researcher needs to use critical thinking to avoid committing any errors such as choosing the wrong hypothesis. Although the hypothesis is considered the first step before further investigations such as data collection for the experiment, the hypothesis formulation also requires some amount of data collection. The data collection for the hypothesis formulation refers to the review of literature related to the concerned topic, and understanding of the previous research on the related topic. Following are some of the main sources of the hypothesis that may help the researcher to formulate a good hypothesis.

- Reviewing the similar studies and literature related to a similar problem.

- Examining the available data concerned with the problem.

- Discussing the problem with the colleagues, or the professional researchers about the problem under investigation.

- Thorough research and investigation by conducting field interviews or surveys on the people that are directly concerned with the problem under investigation.

- Sometimes ‘institution’ of the well known and experienced researcher is also considered as a good source of the hypothesis formulation.

Real Life Hypothesis Examples

1. null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis examples.

Every research problem-solving procedure begins with the formulation of the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis. The alternative hypothesis assumes the existence of the relationship between the variables under study, while the null hypothesis denies the relationship between the variables under study. Following are examples of the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis based on the research problem.

Research Problem: What is the benefit of eating an apple daily on your health?

Alternative Hypothesis: Eating an apple daily reduces the chances of visiting the doctor.

Null Hypothesis : Eating an apple daily does not impact the frequency of visiting the doctor.

Research Problem: What is the impact of spending a lot of time on mobiles on the attention span of teenagers.

Alternative Problem: Spending time on the mobiles and attention span have a negative correlation.

Null Hypothesis: There does not exist any correlation between the use of mobile by teenagers on their attention span.

Research Problem: What is the impact of providing flexible working hours to the employees on the job satisfaction level.

Alternative Hypothesis : Employees who get the option of flexible working hours have better job satisfaction than the employees who don’t get the option of flexible working hours.

Null Hypothesis: There is no association between providing flexible working hours and job satisfaction.

2. Simple Hypothesis Examples

The hypothesis that includes only one independent variable (predictor variable) and one dependent variable (outcome variable) is termed the simple hypothesis. For example, the children are more likely to get clinical depression if their parents had also suffered from the clinical depression. Here, the independent variable is the parents suffering from clinical depression and the dependent or the outcome variable is the clinical depression observed in their child/children. Other examples of the simple hypothesis are given below,

- If the management provides the official snack breaks to the employees, the employees are less likely to take the off-site breaks. Here, providing snack breaks is the independent variable and the employees are less likely to take the off-site break is the dependent variable.

3. Complex Hypothesis Examples

If the hypothesis includes more than one independent (predictor variable) or more than one dependent variable (outcome variable) it is known as the complex hypothesis. For example, clinical depression in children is associated with a family clinical depression history and a stressful and hectic lifestyle. In this case, there are two independent variables, i.e., family history of clinical depression and hectic and stressful lifestyle, and one dependent variable, i.e., clinical depression. Following are some more examples of the complex hypothesis,

4. Logical Hypothesis Examples

If there are not many pieces of evidence and studies related to the concerned problem, then the researcher can take the help of the general logic to formulate the hypothesis. The logical hypothesis is proved true through various logic. For example, if the researcher wants to prove that the animal needs water for its survival, then this can be logically verified through the logic that ‘living beings can not survive without the water.’ Following are some more examples of logical hypotheses,

- Tia is not good at maths, hence she will not choose the accounting sector as her career.

- If there is a correlation between skin cancer and ultraviolet rays, then the people who are more exposed to the ultraviolet rays are more prone to skin cancer.

- The beings belonging to the different planets can not breathe in the earth’s atmosphere.

- The creatures living in the sea use anaerobic respiration as those living outside the sea use aerobic respiration.

5. Empirical Hypothesis Examples

The empirical hypothesis comes into existence when the statement is being tested by conducting various experiments. This hypothesis is not just an idea or notion, instead, it refers to the statement that undergoes various trials and errors, and various extraneous variables can impact the result. The trials and errors provide a set of results that can be testable over time. Following are the examples of the empirical hypothesis,

- The hungry cat will quickly reach the endpoint through the maze, if food is placed at the endpoint then the cat is not hungry.

- The people who consume vitamin c have more glowing skin than the people who consume vitamin E.

- Hair growth is faster after the consumption of Vitamin E than vitamin K.

- Plants will grow faster with fertilizer X than with fertilizer Y.

6. Statistical Hypothesis Examples

The statements that can be proven true by using the various statistical tools are considered the statistical hypothesis. The researcher uses statistical data about an area or the group in the analysis of the statistical hypothesis. For example, if you study the IQ level of the women belonging to nation X, it would be practically impossible to measure the IQ level of each woman belonging to nation X. Here, statistical methods come to the rescue. The researcher can choose the sample population, i.e., women belonging to the different states or provinces of the nation X, and conduct the statistical tests on this sample population to get the average IQ of the women belonging to the nation X. Following are the examples of the statistical hypothesis.

- 30 per cent of the women belonging to the nation X are working.

- 50 per cent of the people living in the savannah are above the age of 70 years.

- 45 per cent of the poor people in the United States are uneducated.

Significance of Hypothesis

A hypothesis is very crucial in experimental research as it aims to predict any particular outcome of the experiment. Hypothesis plays an important role in guiding the researchers to focus on the concerned area of research only. However, the hypothesis is not required by all researchers. The type of research that seeks for finding facts, i.e., historical research, does not need the formulation of the hypothesis. In the historical research, the researchers look for the pieces of evidence related to the human life, the history of a particular area, or the occurrence of any event, this means that the researcher does not have a strong basis to make an assumption in these types of researches, hence hypothesis is not needed in this case. As stated by Hillway (1964)

When fact-finding alone is the aim of the study, a hypothesis is not required.”

The hypothesis may not be an important part of the descriptive or historical studies, but it is a crucial part for the experimental researchers. Following are some of the points that show the importance of formulating a hypothesis before conducting the experiment.

- Hypothesis provides a tentative statement about the outcome of the experiment that can be validated and tested. It helps the researcher to directly focus on the problem under investigation by collecting the relevant data according to the variables mentioned in the hypothesis.

- Hypothesis facilitates a direction to the experimental research. It helps the researcher in analysing what is relevant for the study and what’s not. It prevents the researcher’s time as he does not need to waste time on reviewing the irrelevant research and literature, and also prevents the researcher from collecting the irrelevant data.

- Hypothesis helps the researcher in choosing the appropriate sample, statistical tests to conduct, variables to be studied and the research methodology. The hypothesis also helps the study from being generalised as it focuses on the limited and exact problem under investigation.

- Hypothesis act as a framework for deducing the outcomes of the experiment. The researcher can easily test the different hypotheses for understanding the interaction among the various variables involved in the study. On this basis of the results obtained from the testing of various hypotheses, the researcher can formulate the final meaningful report.

Related Posts

25 Fallacy Examples in Real Life

13 Examples Of Operant Conditioning in Everyday Life

Halo Effect Examples

10 Examples of Esteem Needs (Maslow’s Hierarchy)

Bounded Ethicality

4 Behavioral Ethics Examples

Add comment cancel reply.

- General Categories

- Mental Health

- IQ and Intelligence

- Bipolar Disorder

Psychological Hypothesis: Formulating and Testing Ideas in Psychology

A well-crafted psychological hypothesis acts as a guiding light, illuminating the path to groundbreaking discoveries and unraveling the mysteries of the human mind. It’s the spark that ignites curiosity, the compass that directs research, and the foundation upon which our understanding of human behavior is built. But what exactly is a psychological hypothesis, and why is it so crucial to the field of psychology?

Let’s embark on a journey through the fascinating world of psychological hypotheses, exploring their nature, types, and the art of crafting them. Along the way, we’ll uncover the secrets that make these scientific propositions so powerful in advancing our knowledge of the human psyche.

The Essence of Psychological Hypotheses: More Than Just Educated Guesses

At its core, a psychological hypothesis is an educated guess about the relationship between variables in human behavior or mental processes. It’s a tentative explanation for an observed phenomenon, waiting to be put to the test. But don’t be fooled by its seemingly simple definition – a well-formulated hypothesis is the result of careful observation, critical thinking, and a deep understanding of psychological principles.

Imagine you’re a psychologist studying the effects of social media on teenage self-esteem. You’ve noticed that many teens seem to feel worse about themselves after scrolling through Instagram. This observation might lead you to form a hypothesis: “Increased time spent on Instagram is associated with lower self-esteem in teenagers.” This statement is more than just a hunch; it’s a testable prediction based on your knowledge and observations.

The importance of hypotheses in psychological research cannot be overstated. They serve as the bridge between questions and answers, guiding researchers in their quest for knowledge. Without hypotheses, psychology would be a field of aimless observations, lacking the structure needed to make meaningful discoveries.

The history of hypothesis testing in psychology is as old as the field itself. From Wilhelm Wundt’s early experiments in the late 19th century to modern-day neuroscientific studies, hypotheses have been the driving force behind psychological inquiry. They’ve helped us understand everything from the basic principles of learning to the complex mechanisms of memory and emotion.

The Anatomy of a Psychological Hypothesis: What Sets It Apart?

So, what makes a psychological hypothesis different from hypotheses in other scientific fields? While all scientific hypotheses share some common characteristics, psychological hypotheses often deal with more abstract concepts and complex human behaviors.

A well-formulated psychological hypothesis should be:

1. Specific and clear 2. Testable through empirical observation or experimentation 3. Falsifiable (capable of being proven wrong) 4. Relevant to existing psychological theories or observations 5. Ethical to test

Let’s break down an example to see these characteristics in action. Consider the famous hypothetical thought in psychology experiment by Stanley Milgram on obedience to authority. His hypothesis might have been: “Individuals are more likely to obey authority figures even when it conflicts with their personal moral beliefs.” This hypothesis is specific, testable, falsifiable, relevant to social psychology theories, and (albeit controversially) ethical to test.

The role of hypotheses in the scientific method is crucial. They serve as the starting point for the entire research process, guiding the design of experiments, the collection of data, and the interpretation of results. In psychology, this process is often referred to as hypothetical-deductive reasoning , where researchers start with a theory, derive a hypothesis, and then test it through observation or experimentation.

The Many Faces of Psychological Hypotheses: A Typology

Just as there are many flavors of ice cream, there are various types of psychological hypotheses. Understanding these different types can help researchers choose the most appropriate approach for their studies.

1. Null Hypothesis vs. Alternative Hypothesis

The null hypothesis (H0) states that there is no relationship between the variables being studied. It’s the hypothesis that researchers try to disprove. For example, “There is no relationship between sleep duration and academic performance in college students.”

The alternative hypothesis (H1 or Ha) is the opposite of the null hypothesis. It suggests that there is a relationship between the variables. Using the same example: “There is a relationship between sleep duration and academic performance in college students.”

2. Directional Hypothesis in Psychology

A directional hypothesis predicts not only that there’s a relationship between variables but also specifies the nature of that relationship. For instance, “Increased sleep duration is associated with improved academic performance in college students.”

3. Non-directional Hypothesis

This type of hypothesis predicts a relationship between variables but doesn’t specify the direction. For example, “There is a relationship between sleep duration and academic performance in college students, but the nature of this relationship is unknown.”

4. Research Hypothesis vs. Statistical Hypothesis

A research hypothesis is a broader statement about the expected relationship between variables, often based on psychological theories . A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a more specific, mathematically testable statement derived from the research hypothesis.

Understanding these different types of hypotheses is crucial for anyone delving into psychological research. It’s like having a toolbox – knowing which tool to use for which job makes the work much more effective and efficient.

The Art of Crafting a Psychological Hypothesis: A Step-by-Step Guide

Now that we’ve explored the different types of hypotheses, let’s roll up our sleeves and learn how to write one. Crafting a good hypothesis is part science, part art, and a whole lot of critical thinking.

Step 1: Start with a Research Question

Every good hypothesis begins with a compelling research question. For example, “Does mindfulness meditation reduce symptoms of anxiety in college students?”

Step 2: Review Existing Literature

Before formulating your hypothesis, dive into the existing research. What have other studies found? Are there gaps in our current understanding? This step helps ensure your hypothesis is grounded in existing knowledge and contributes something new to the field.

Step 3: Identify Variables and Their Relationships

Clearly define your variables. In our example, the independent variable would be “mindfulness meditation practice,” and the dependent variable would be “symptoms of anxiety.”

Step 4: Use Operational Definitions

Operational definitions are crucial in psychology. They specify how you will measure your variables. For instance, “mindfulness meditation practice” might be defined as “20 minutes of guided meditation daily for 8 weeks,” while “symptoms of anxiety” could be measured using a specific anxiety scale.

Step 5: Formulate Your Hypothesis

Now you’re ready to write your hypothesis. A possible directional hypothesis might be: “College students who practice mindfulness meditation for 20 minutes daily over 8 weeks will show a greater reduction in anxiety symptoms compared to those who do not practice meditation.”

Common Mistakes to Avoid:

1. Being too vague or broad 2. Including untestable elements 3. Failing to consider alternative explanations 4. Ignoring ethical considerations 5. Not aligning with existing psychological theories

Remember, crafting a good hypothesis is a skill that improves with practice. Don’t be afraid to revise and refine your hypotheses as you gain more knowledge and experience.

Directional Hypothesis: A Closer Look at This Powerful Tool

Let’s zoom in on directional hypotheses, as they’re particularly common and useful in psychological research. A directional hypothesis, as we’ve mentioned, predicts not just a relationship between variables, but also the nature or direction of that relationship.

When to Use a Directional Hypothesis:

1. When previous research strongly suggests a specific direction of effect 2. When you have a solid theoretical basis for predicting the direction 3. When you’re replicating a study with well-established findings

Advantages of Directional Hypotheses:

1. They’re more specific, which can lead to more focused research designs 2. They can be more powerful in statistical testing 3. They demonstrate a deeper understanding of the subject matter

Disadvantages:

1. They’re riskier – if you’re wrong about the direction, your hypothesis is entirely rejected 2. They can potentially bias researchers towards confirming their expectations

Examples of Directional Hypotheses in Psychological Research:

1. “Exposure to violent video games increases aggressive behavior in adolescents.” 2. “Higher levels of social support are associated with lower rates of depression in elderly individuals.” 3. “Students who use spaced repetition techniques will perform better on memory tests compared to those who use cramming techniques.”

Putting Hypotheses to the Test: The Crucible of Psychological Research

Formulating a hypothesis is just the beginning. The real excitement comes when we put these ideas to the test through carefully designed experiments and rigorous statistical analysis.

Designing Experiments to Test Hypotheses:

The key to a good experiment is control. Researchers must carefully manipulate the independent variable while controlling for potential confounding factors. For instance, in our mindfulness meditation example, we’d need to ensure that both the meditation group and the control group are similar in terms of initial anxiety levels, age, gender distribution, and other relevant factors.

Statistical Analysis and Hypothesis Testing:

Once the data is collected, it’s time for statistical analysis. This is where we determine whether our results support or refute our hypothesis. Common statistical tests in psychology include t-tests, ANOVAs, and regression analyses. The choice of test depends on the nature of your variables and the design of your study.

Interpreting Results and Drawing Conclusions:

After running the statistical tests, researchers must interpret the results carefully. It’s important to remember that failing to reject the null hypothesis is not the same as proving it true. Similarly, finding a statistically significant result doesn’t necessarily mean the effect is practically significant or meaningful.

Replication and Reproducibility:

In recent years, psychology has faced a “replication crisis,” with many well-known studies failing to replicate. This highlights the importance of replication in psychological research. A single study, no matter how well-designed, is rarely enough to establish a finding as fact. Replication across different labs, populations, and contexts is crucial for building a solid foundation of psychological knowledge.

The Future of Hypothesis Testing in Psychology: New Frontiers and Challenges

As we look to the future, the landscape of hypothesis testing in psychology is evolving. New technologies, such as neuroimaging and big data analytics, are opening up exciting possibilities for testing more complex hypotheses about brain function and behavior.

At the same time, there’s a growing recognition of the limitations of traditional null hypothesis significance testing. Some researchers are advocating for more nuanced approaches, such as Bayesian statistics or effect size estimation, which can provide richer information about the strength and practical significance of psychological effects.

There’s also an increasing emphasis on pre-registration of studies and open science practices. These approaches aim to increase transparency and reduce bias in the research process, ultimately leading to more reliable and reproducible findings.

As we wrap up our exploration of psychological hypotheses, it’s clear that these scientific propositions are far more than mere guesses. They are the lifeblood of psychological research, driving our understanding of the human mind and behavior forward.

From the careful formulation of a research question to the rigorous testing of hypotheses, each step in the process contributes to the grand tapestry of psychological knowledge. As we continue to refine our methods and explore new frontiers, the humble hypothesis remains our trusty guide, leading us towards ever-greater insights into the complexities of human nature.

So the next time you find yourself pondering a question about human behavior or mental processes, remember: you’re not just daydreaming – you might be on the verge of formulating the next groundbreaking psychological hypothesis. After all, every great discovery starts with a simple question and a testable idea. Who knows where your curiosity might lead?

References:

1. Goodwin, C. J., & Goodwin, K. A. (2016). Research in Psychology: Methods and Design. John Wiley & Sons.

2. Shaughnessy, J. J., Zechmeister, E. B., & Zechmeister, J. S. (2015). Research Methods in Psychology. McGraw-Hill Education.

3. American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). American Psychological Association.

4. Cumming, G. (2014). The New Statistics: Why and How. Psychological Science, 25(1), 7-29. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0956797613504966

5. Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349(6251), aac4716. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/349/6251/aac4716

6. Nosek, B. A., Ebersole, C. R., DeHaven, A. C., & Mellor, D. T. (2018). The preregistration revolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(11), 2600-2606. https://www.pnas.org/content/115/11/2600

7. Wagenmakers, E. J., Marsman, M., Jamil, T., Ly, A., Verhagen, J., Love, J., … & Morey, R. D. (2018). Bayesian inference for psychology. Part I: Theoretical advantages and practical ramifications. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 25(1), 35-57.

8. Maxwell, S. E., Lau, M. Y., & Howard, G. S. (2015). Is psychology suffering from a replication crisis? What does “failure to replicate” really mean? American Psychologist, 70(6), 487-498.

9. Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., & Simonsohn, U. (2011). False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychological Science, 22(11), 1359-1366.

10. Lakens, D. (2013). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 863. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863/full

Was this article helpful?

Would you like to add any comments (optional), leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Related Resources

Brain Samples: Unlocking the Secrets of Neuroscience

Discover Psychology Impact Factor: Exploring the Journal’s Influence and Significance

Confidence Intervals in Psychology: Enhancing Statistical Interpretation and Research Validity

Control Condition in Psychology: Definition, Purpose, and Applications

Dependent Variables in Psychology: Definition, Examples, and Importance

Debriefing in Psychology: Definition, Purpose, and Techniques

Correlation in Psychology: Definition, Types, and Applications

Data Collection Methods in Psychology: Essential Techniques for Researchers

Histogram in Psychology: Definition, Applications, and Significance

Dimensional vs Categorical Approach in Psychology: Comparing Methods of Classification

- Privacy Policy

Home » What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

In research, a hypothesis is a clear, testable statement predicting the relationship between variables or the outcome of a study. Hypotheses form the foundation of scientific inquiry, providing a direction for investigation and guiding the data collection and analysis process. Hypotheses are typically used in quantitative research but can also inform some qualitative studies by offering a preliminary assumption about the subject being explored.

A hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction or statement that suggests an expected relationship between variables in a study. It acts as a starting point, guiding researchers to examine whether their predictions hold true based on collected data. For a hypothesis to be useful, it must be clear, concise, and based on prior knowledge or theoretical frameworks.

Key Characteristics of a Hypothesis :

- Testable : Must be possible to evaluate or observe the outcome through experimentation or analysis.

- Specific : Clearly defines variables and the expected relationship or outcome.

- Predictive : States an anticipated effect or association that can be confirmed or refuted.

Example : “Increasing the amount of daily physical exercise will lead to a reduction in stress levels among college students.”

Types of Hypotheses

Hypotheses can be categorized into several types, depending on their structure, purpose, and the type of relationship they suggest. The most common types include null hypothesis , alternative hypothesis , directional hypothesis , and non-directional hypothesis .

1. Null Hypothesis (H₀)

Definition : The null hypothesis states that there is no relationship between the variables being studied or that any observed effect is due to chance. It serves as the default position, which researchers aim to test against to determine if a significant effect or association exists.

Purpose : To provide a baseline that can be statistically tested to verify if a relationship or difference exists.

Example : “There is no difference in academic performance between students who receive additional tutoring and those who do not.”

2. Alternative Hypothesis (H₁ or Hₐ)

Definition : The alternative hypothesis proposes that there is a relationship or effect between variables. This hypothesis contradicts the null hypothesis and suggests that any observed result is not due to chance.

Purpose : To present an expected outcome that researchers aim to support with data.

Example : “Students who receive additional tutoring will perform better academically than those who do not.”

3. Directional Hypothesis

Definition : A directional hypothesis specifies the direction of the expected relationship between variables, predicting either an increase, decrease, positive, or negative effect.

Purpose : To provide a more precise prediction by indicating the expected direction of the relationship.

Example : “Increasing the duration of daily exercise will lead to a decrease in stress levels among adults.”

4. Non-Directional Hypothesis

Definition : A non-directional hypothesis states that there is a relationship between variables but does not specify the direction of the effect.

Purpose : To allow for exploration of the relationship without committing to a particular direction.

Example : “There is a difference in stress levels between adults who exercise regularly and those who do not.”

Examples of Hypotheses in Different Fields

- Null Hypothesis : “There is no difference in anxiety levels between individuals who practice mindfulness and those who do not.”

- Alternative Hypothesis : “Individuals who practice mindfulness will report lower anxiety levels than those who do not.”

- Directional Hypothesis : “Providing feedback will improve students’ motivation to learn.”

- Non-Directional Hypothesis : “There is a difference in motivation levels between students who receive feedback and those who do not.”

- Null Hypothesis : “There is no association between diet and energy levels among teenagers.”

- Alternative Hypothesis : “A balanced diet is associated with higher energy levels among teenagers.”

- Directional Hypothesis : “An increase in employee engagement activities will lead to improved job satisfaction.”

- Non-Directional Hypothesis : “There is a relationship between employee engagement activities and job satisfaction.”

- Null Hypothesis : “The introduction of green spaces does not affect urban air quality.”

- Alternative Hypothesis : “Green spaces improve urban air quality.”

Writing Guide for Hypotheses

Writing a clear, testable hypothesis involves several steps, starting with understanding the research question and selecting variables. Here’s a step-by-step guide to writing an effective hypothesis.

Step 1: Identify the Research Question

Start by defining the primary research question you aim to investigate. This question should be focused, researchable, and specific enough to allow for hypothesis formation.

Example : “Does regular physical exercise improve mental well-being in college students?”

Step 2: Conduct Background Research

Review relevant literature to gain insight into existing theories, studies, and gaps in knowledge. This helps you understand prior findings and guides you in forming a logical hypothesis based on evidence.

Example : Research shows a positive correlation between exercise and mental well-being, which supports forming a hypothesis in this area.

Step 3: Define the Variables

Identify the independent and dependent variables. The independent variable is the factor you manipulate or consider as the cause, while the dependent variable is the outcome or effect you are measuring.

- Independent Variable : Amount of physical exercise

- Dependent Variable : Mental well-being (measured through self-reported stress levels)

Step 4: Choose the Hypothesis Type

Select the hypothesis type based on the research question. If you predict a specific outcome or direction, use a directional hypothesis. If not, a non-directional hypothesis may be suitable.

Example : “Increasing the frequency of physical exercise will reduce stress levels among college students” (directional hypothesis).

Step 5: Write the Hypothesis

Formulate the hypothesis as a clear, concise statement. Ensure it is specific, testable, and focuses on the relationship between the variables.

Example : “College students who exercise at least three times per week will report lower stress levels than those who do not exercise regularly.”

Step 6: Test and Refine (Optional)

In some cases, it may be necessary to refine the hypothesis after conducting a preliminary test or pilot study. This ensures that your hypothesis is realistic and feasible within the study parameters.

Tips for Writing an Effective Hypothesis

- Use Clear Language : Avoid jargon or ambiguous terms to ensure your hypothesis is easily understandable.

- Be Specific : Specify the expected relationship between the variables, and, if possible, include the direction of the effect.

- Ensure Testability : Frame the hypothesis in a way that allows for empirical testing or observation.

- Focus on One Relationship : Avoid complexity by focusing on a single, clear relationship between variables.

- Make It Measurable : Choose variables that can be quantified or observed to simplify data collection and analysis.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Vague Statements : Avoid vague hypotheses that don’t specify a clear relationship or outcome.

- Unmeasurable Variables : Ensure that the variables in your hypothesis can be observed, measured, or quantified.

- Overly Complex Hypotheses : Keep the hypothesis simple and focused, especially for beginner researchers.

- Using Personal Opinions : Avoid subjective or biased language that could impact the neutrality of the hypothesis.

Examples of Well-Written Hypotheses

- Psychology : “Adolescents who spend more than two hours on social media per day will report higher levels of anxiety than those who spend less than one hour.”

- Business : “Increasing customer service training will improve customer satisfaction ratings among retail employees.”

- Health : “Consuming a diet rich in fruits and vegetables is associated with lower cholesterol levels in adults.”

- Education : “Students who participate in active learning techniques will have higher retention rates compared to those in traditional lecture-based classrooms.”

- Environmental Science : “Urban areas with more green spaces will report lower average temperatures than those with minimal green coverage.”

A well-formulated hypothesis is essential to the research process, providing a clear and testable prediction about the relationship between variables. Understanding the different types of hypotheses, following a structured writing approach, and avoiding common pitfalls help researchers create hypotheses that effectively guide data collection, analysis, and conclusions. Whether working in psychology, education, health sciences, or any other field, an effective hypothesis sharpens the focus of a study and enhances the rigor of research.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Trochim, W. M. K. (2006). The Research Methods Knowledge Base (3rd ed.). Atomic Dog Publishing.

- McLeod, S. A. (2019). What is a Hypothesis? Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/what-is-a-hypotheses.html

- Walliman, N. (2017). Research Methods: The Basics (2nd ed.). Routledge.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Methodology – Types, Examples and...

Theoretical Framework – Types, Examples and...

Thesis Statement – Examples, Writing Guide

Ethical Considerations – Types, Examples and...

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Chapter Summary & Overview – Writing Guide...

Learning Materials

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English Literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Formulation of Hypothesis

Children who spend more time playing outside are more likely to be imaginative. What do you think this statement is an example of in terms of scientific research ? If you guessed a hypothesis, then you'd be correct. The formulation of hypotheses is a fundamental step in psychology research.

Millions of flashcards designed to help you ace your studies

- Cell Biology

What type of hypothesis matches the following definition. A hypothesis that states that the IV will influence the DV, and states how it will influence the DV.

Which type of hypothesis is also known as a two-tailed hypothesis?

What type of hypothesis matches the following definition. A predictive statement that researchers use when it is thought that the IV will not influence the DV.

What type of hypothesis is the following example. There will be no observed difference in scores from a memory performance task between people with high- or low-depressive scores.

Is the following example a falsifiable hypothesis, "leprechauns always find the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow".

What type of hypothesis is the following example. There will be an observed difference in scores from a memory performance task between people with high- or low-depressive scores.

Is memory an operationalised variable that could be used in a good hypothesis?

What type of hypothesis is the following example. People with low depressive scores will perform better in the memory performance task than people who score higher in depressive symptoms.

What type of hypothesis matches the following definition. A hypothesis that states that the IV will influence the DV. But, the hypothesis does not state how the IV will influence the DV.

Achieve better grades quicker with Premium

Geld-zurück-Garantie, wenn du durch die Prüfung fällst

Review generated flashcards

to start learning or create your own AI flashcards

Start learning or create your own AI flashcards

StudySmarter Editorial Team

Team Formulation of Hypothesis Teachers

- 8 minutes reading time

- Checked by StudySmarter Editorial Team

- Approaches in Psychology

- Basic Psychology

- Biological Bases of Behavior

- Biopsychology

- Careers in Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Bartlett War of the Ghosts

- Brain Development

- Bruner and Minturn Study of Perceptual Set

- Case Studies Psychology

- Computation

- Conservation of Number Piaget

- Constructive Processes in Memory

- Correlation

- Data handling

- Depth Cues Psychology

- Designing Research

- Developmental Research

- Dweck's Theory of Mindset

- Ethical considerations in research

- Experimental Method

- Factors Affecting Perception

- Factors Affecting the Accuracy of Memory

- Gibson's Theory of Direct Perception

- Gregory's Constructivist Theory of Perception

- Gunderson et al 2013 study

- Hughes Policeman Doll Study

- Issues and Debates in Developmental Psychology

- Language and Perception

- McGarrigle and Donaldson Naughty Teddy

- Memory Processes

- Memory recall

- Nature and Nurture in Development

- Normal Distribution Psychology

- Perception Research

- Perceptual Set

- Piagets Theory in Education

- Planning and Conducting Research

- Population Samples

- Primary and Secondary Data

- Quantitative Data

- Quantitative and Qualitative Data

- Quantitative and Qualitative Methods

- Research Procedures

- Serial Position Effect

- Short-term Retention

- Structures of Memory

- Tables, Charts and Graphs

- The Effects of Learning on Development

- The Gilchrist And Nesberg Study Of Motivation

- Three Mountains Task

- Types of Variable

- Types of bias and how to control

- Visual Cues and Constancies

- Visual illusions

- Willingham's Learning Theory

- Cognition and Development

- Cognitive Psychology

- Data Handling and Analysis

- Developmental Psychology

- Eating Behaviour

- Emotion and Motivation

- Famous Psychologists

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- Individual Differences Psychology

- Issues and Debates in Psychology

- Personality in Psychology

- Psychological Treatment

- Psychology and Environment

- Relationships

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Schizophrenia

- Scientific Foundations of Psychology

- Scientific Investigation

- Sensation and Perception

- Social Context of Behaviour

- Social Psychology

Jump to a key chapter

- First, we will discuss the importance of hypotheses in research.

- We will then cover formulating hypotheses in research, including the steps in the formulation of hypotheses in research methodology.

- We will provide examples of hypotheses in research throughout the explanation.

- Finally, we will delve into the different types of hypotheses in research.

What is a Hypothesis?

The current community of psychologists believe that the best approach to understanding behaviour is to conduct scientific research . To be classed as scientific research , it must be observable, valid, reliable and follow a standardised procedure.

One of the important steps in scientific research is to formulate a hypothesis before starting the study procedure.

The hypothesis is a predictive, testable statement predicting the outcome and the results the researcher expects to find.

The hypothesis provides a summary of what direction, if any, is taken to investigate a theory.

In scientific research, there is a criterion that hypotheses need to be met to be regarded as acceptable.

If a hypothesis is disregarded, the research may be rejected by the community of psychology researchers.

Importance of Hypothesis in Research

The purpose of including hypotheses in psychology research is:

- To provide a summary of the research, how it will be investigated, and what is expected to be found.

- To provide an answer to the research question.

When carrying out research, researchers first investigate the research area they are interested in. From this, researchers are required to identify a gap in the literature.

Filling the gap essentially means finding what previous work has not been explained yet, investigated to a sufficient degree, or simply expanding or further investigating a theory if doubt exists.

The researcher then forms a research question that the researcher will attempt to answer in their study.

Remember, the hypothesis is a predictive statement of what is expected to happen when testing the research question.

The hypothesis can be used for later data analysis. This includes inferential tests such as hypothesis testing and identifying if statistical findings are significant.

Steps in the Formulation of Hypothesis in Research Methodology

Researchers must follow certain steps to formulate testable hypotheses when conducting research.

Overall, the researcher has to consider the direction of the research, i.e. will it be looking for a difference caused by independent variables ? Or will it be more concerned with the correlation between variables?

All researchers will likely complete the following.

- Investigating background research in the area of interest.

- Formulating or investigating a theory.

- Identify how the theory will be tested and what the researcher expects to find based on relevant, previously published scientific works.

The above steps are used to formulate testable hypotheses.

The Formulation of Testable Hypotheses

The hypothesis is important in research as it indicates what and how a variable will be investigated.

The hypothesis essentially summarises what and how something will be investigated. This is important as it ensures that the researcher has carefully planned how the research will be done, as the researchers have to follow a set procedure to conduct research.

This is known as the scientific method.

Formulating Hypotheses in Research

When formulating hypotheses, things that researchers should consider are:

Types of Hypotheses in Research

Researchers can propose different types of hypotheses when carrying out research.

The following research scenario will be discussed to show examples of each type of hypothesis that the researchers could use. "A research team was investigating whether memory performance is affected by depression ."

The identified independent variable is the severity of depression scores, and the dependent variable is the scores from a memory performance task.

The null hypothesis predicts that the results will show no or little effect. The null hypothesis is a predictive statement that researchers use when it is thought that the IV will not influence the DV.

In this case, the null hypothesis would be there will be no difference in memory scores on the MMSE test of those who are diagnosed with depression and those who are not.

An alternative hypothesis is a predictive statement used when it is thought that the IV will influence the DV. The alternative hypothesis is also called a non-directional, two-tailed hypothesis, as it predicts the results can go either way, e.g. increase or decrease.

The example in this scenario is there will be an observed difference in scores from a memory performance task between people with high- or low-depressive scores.

The directional alternative hypothesis states how the IV will influence the DV, identifying a specific direction, such as if there will be an increase or decrease in the observed results.

The example in this scenario is people with low depressive scores will perform better in the memory performance task than people who score higher in depressive symptoms.

Example Hypothesis in Research

To summarise, let's look at an example of a straightforward hypothesis that indicates the relationship between two variables: the independent and the dependent.

If you stay up late, you will feel tired the following day; the more caffeine you drink, the harder you find it to fall asleep, or the more sunlight plants get, the taller they will grow.

Formulation of Hypothesis - Key Takeaways

- The current community of psychologists believe that the best approach to understanding behaviour is to conduct scientific research. One of the important steps in scientific research is to create a hypothesis.

- The hypothesis is a predictive, testable statement concerning the outcome/results that the researcher expects to find.

- Hypotheses are needed in research to provide a summary of what the research is, how to investigate a theory and what is expected to be found, and to provide an answer to the research question so that the hypothesis can be used for later data analysis.

- There are requirements for the formulation of testable hypotheses. The hypotheses should identify and operationalise the IV and DV. In addition, they should describe the nature of the relationship between the IV and DV.

- There are different types of hypotheses: Null hypothesis, Alternative hypothesis (this is also known as the non-directional, two-tailed hypothesis), and Directional hypothesis (this is also known as the one-tailed hypothesis).

Flashcards in Formulation of Hypothesis 9

Directional, alternative hypothesis

Alternative hypothesis

Null hypothesis

Learn faster with the 9 flashcards about Formulation of Hypothesis

Sign up for free to gain access to all our flashcards.

Already have an account? Log in

Frequently Asked Questions about Formulation of Hypothesis

What are the 3 types of hypotheses?

The three types of hypotheses are:

- Null hypothesis

- Alternative hypothesis

- Directional/non-directional hypothesis

What is an example of a hypothesis in psychology?

An example of a null hypothesis in psychology is, there will be no observed difference in scores from a memory performance task between people with high- or low-depressive scores.

What are the steps in formulating a hypothesis?

All researchers will likely complete the following

- Investigating background research in the area of interest

- Formulating or investigating a theory

- Identify how the theory will be tested and what the researcher expects to find based on relevant, previously published scientific works

What is formulation of hypothesis in research?

The formulation of a hypothesis in research is when the researcher formulates a predictive statement of what is expected to happen when testing the research question based on background research.

How to formulate null and alternative hypothesis?

When formulating a null hypothesis the researcher would state a prediction that they expect to see no difference in the dependent variable when the independent variable changes or is manipulated. Whereas, when using an alternative hypothesis then it would be predicted that there will be a change in the dependent variable. The researcher can state in which direction they expect the results to go.

Test your knowledge with multiple choice flashcards

That was a fantastic start, you can do better, sign up to create your own flashcards.

Access over 700 million learning materials

Study more efficiently with flashcards

Get better grades with AI

Already have an account? Log in

Keep learning, you are doing great.

Discover learning materials with the free StudySmarter app

About StudySmarter

StudySmarter is a globally recognized educational technology company, offering a holistic learning platform designed for students of all ages and educational levels. Our platform provides learning support for a wide range of subjects, including STEM, Social Sciences, and Languages and also helps students to successfully master various tests and exams worldwide, such as GCSE, A Level, SAT, ACT, Abitur, and more. We offer an extensive library of learning materials, including interactive flashcards, comprehensive textbook solutions, and detailed explanations. The cutting-edge technology and tools we provide help students create their own learning materials. StudySmarter’s content is not only expert-verified but also regularly updated to ensure accuracy and relevance.

Team Psychology Teachers

Study anywhere. Anytime.Across all devices.

Create a free account to save this explanation..

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Join over 22 million students in learning with our StudySmarter App