Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

What the data says about abortion in the U.S.

Pew Research Center has conducted many surveys about abortion over the years, providing a lens into Americans’ views on whether the procedure should be legal, among a host of other questions.

In a Center survey conducted nearly a year after the Supreme Court’s June 2022 decision that ended the constitutional right to abortion , 62% of U.S. adults said the practice should be legal in all or most cases, while 36% said it should be illegal in all or most cases. Another survey conducted a few months before the decision showed that relatively few Americans take an absolutist view on the issue .

Find answers to common questions about abortion in America, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Guttmacher Institute, which have tracked these patterns for several decades:

How many abortions are there in the U.S. each year?

How has the number of abortions in the u.s. changed over time, what is the abortion rate among women in the u.s. how has it changed over time, what are the most common types of abortion, how many abortion providers are there in the u.s., and how has that number changed, what percentage of abortions are for women who live in a different state from the abortion provider, what are the demographics of women who have had abortions, when during pregnancy do most abortions occur, how often are there medical complications from abortion.

This compilation of data on abortion in the United States draws mainly from two sources: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Guttmacher Institute, both of which have regularly compiled national abortion data for approximately half a century, and which collect their data in different ways.

The CDC data that is highlighted in this post comes from the agency’s “abortion surveillance” reports, which have been published annually since 1974 (and which have included data from 1969). Its figures from 1973 through 1996 include data from all 50 states, the District of Columbia and New York City – 52 “reporting areas” in all. Since 1997, the CDC’s totals have lacked data from some states (most notably California) for the years that those states did not report data to the agency. The four reporting areas that did not submit data to the CDC in 2021 – California, Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey – accounted for approximately 25% of all legal induced abortions in the U.S. in 2020, according to Guttmacher’s data. Most states, though, do have data in the reports, and the figures for the vast majority of them came from each state’s central health agency, while for some states, the figures came from hospitals and other medical facilities.

Discussion of CDC abortion data involving women’s state of residence, marital status, race, ethnicity, age, abortion history and the number of previous live births excludes the low share of abortions where that information was not supplied. Read the methodology for the CDC’s latest abortion surveillance report , which includes data from 2021, for more details. Previous reports can be found at stacks.cdc.gov by entering “abortion surveillance” into the search box.

For the numbers of deaths caused by induced abortions in 1963 and 1965, this analysis looks at reports by the then-U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, a precursor to the Department of Health and Human Services. In computing those figures, we excluded abortions listed in the report under the categories “spontaneous or unspecified” or as “other.” (“Spontaneous abortion” is another way of referring to miscarriages.)

Guttmacher data in this post comes from national surveys of abortion providers that Guttmacher has conducted 19 times since 1973. Guttmacher compiles its figures after contacting every known provider of abortions – clinics, hospitals and physicians’ offices – in the country. It uses questionnaires and health department data, and it provides estimates for abortion providers that don’t respond to its inquiries. (In 2020, the last year for which it has released data on the number of abortions in the U.S., it used estimates for 12% of abortions.) For most of the 2000s, Guttmacher has conducted these national surveys every three years, each time getting abortion data for the prior two years. For each interim year, Guttmacher has calculated estimates based on trends from its own figures and from other data.

The latest full summary of Guttmacher data came in the institute’s report titled “Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2020.” It includes figures for 2020 and 2019 and estimates for 2018. The report includes a methods section.

In addition, this post uses data from StatPearls, an online health care resource, on complications from abortion.

An exact answer is hard to come by. The CDC and the Guttmacher Institute have each tried to measure this for around half a century, but they use different methods and publish different figures.

The last year for which the CDC reported a yearly national total for abortions is 2021. It found there were 625,978 abortions in the District of Columbia and the 46 states with available data that year, up from 597,355 in those states and D.C. in 2020. The corresponding figure for 2019 was 607,720.

The last year for which Guttmacher reported a yearly national total was 2020. It said there were 930,160 abortions that year in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, compared with 916,460 in 2019.

- How the CDC gets its data: It compiles figures that are voluntarily reported by states’ central health agencies, including separate figures for New York City and the District of Columbia. Its latest totals do not include figures from California, Maryland, New Hampshire or New Jersey, which did not report data to the CDC. ( Read the methodology from the latest CDC report .)

- How Guttmacher gets its data: It compiles its figures after contacting every known abortion provider – clinics, hospitals and physicians’ offices – in the country. It uses questionnaires and health department data, then provides estimates for abortion providers that don’t respond. Guttmacher’s figures are higher than the CDC’s in part because they include data (and in some instances, estimates) from all 50 states. ( Read the institute’s latest full report and methodology .)

While the Guttmacher Institute supports abortion rights, its empirical data on abortions in the U.S. has been widely cited by groups and publications across the political spectrum, including by a number of those that disagree with its positions .

These estimates from Guttmacher and the CDC are results of multiyear efforts to collect data on abortion across the U.S. Last year, Guttmacher also began publishing less precise estimates every few months , based on a much smaller sample of providers.

The figures reported by these organizations include only legal induced abortions conducted by clinics, hospitals or physicians’ offices, or those that make use of abortion pills dispensed from certified facilities such as clinics or physicians’ offices. They do not account for the use of abortion pills that were obtained outside of clinical settings .

(Back to top)

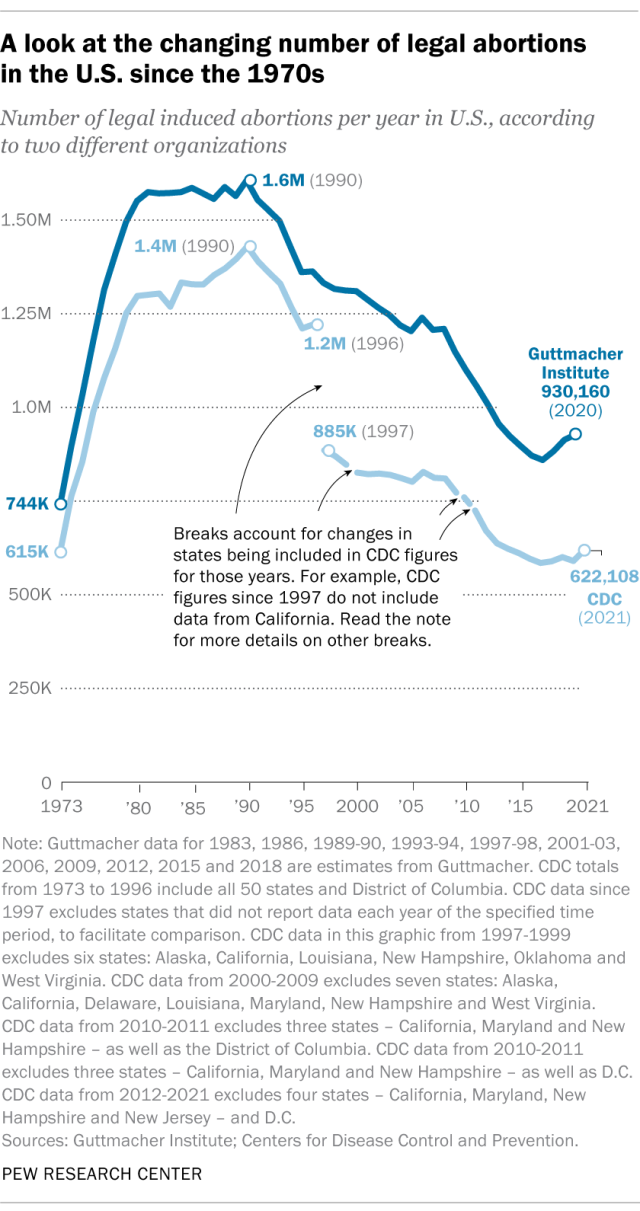

The annual number of U.S. abortions rose for years after Roe v. Wade legalized the procedure in 1973, reaching its highest levels around the late 1980s and early 1990s, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher. Since then, abortions have generally decreased at what a CDC analysis called “a slow yet steady pace.”

Guttmacher says the number of abortions occurring in the U.S. in 2020 was 40% lower than it was in 1991. According to the CDC, the number was 36% lower in 2021 than in 1991, looking just at the District of Columbia and the 46 states that reported both of those years.

(The corresponding line graph shows the long-term trend in the number of legal abortions reported by both organizations. To allow for consistent comparisons over time, the CDC figures in the chart have been adjusted to ensure that the same states are counted from one year to the next. Using that approach, the CDC figure for 2021 is 622,108 legal abortions.)

There have been occasional breaks in this long-term pattern of decline – during the middle of the first decade of the 2000s, and then again in the late 2010s. The CDC reported modest 1% and 2% increases in abortions in 2018 and 2019, and then, after a 2% decrease in 2020, a 5% increase in 2021. Guttmacher reported an 8% increase over the three-year period from 2017 to 2020.

As noted above, these figures do not include abortions that use pills obtained outside of clinical settings.

Guttmacher says that in 2020 there were 14.4 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. Its data shows that the rate of abortions among women has generally been declining in the U.S. since 1981, when it reported there were 29.3 abortions per 1,000 women in that age range.

The CDC says that in 2021, there were 11.6 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. (That figure excludes data from California, the District of Columbia, Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey.) Like Guttmacher’s data, the CDC’s figures also suggest a general decline in the abortion rate over time. In 1980, when the CDC reported on all 50 states and D.C., it said there were 25 abortions per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44.

That said, both Guttmacher and the CDC say there were slight increases in the rate of abortions during the late 2010s and early 2020s. Guttmacher says the abortion rate per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44 rose from 13.5 in 2017 to 14.4 in 2020. The CDC says it rose from 11.2 per 1,000 in 2017 to 11.4 in 2019, before falling back to 11.1 in 2020 and then rising again to 11.6 in 2021. (The CDC’s figures for those years exclude data from California, D.C., Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey.)

The CDC broadly divides abortions into two categories: surgical abortions and medication abortions, which involve pills. Since the Food and Drug Administration first approved abortion pills in 2000, their use has increased over time as a share of abortions nationally, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher.

The majority of abortions in the U.S. now involve pills, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher. The CDC says 56% of U.S. abortions in 2021 involved pills, up from 53% in 2020 and 44% in 2019. Its figures for 2021 include the District of Columbia and 44 states that provided this data; its figures for 2020 include D.C. and 44 states (though not all of the same states as in 2021), and its figures for 2019 include D.C. and 45 states.

Guttmacher, which measures this every three years, says 53% of U.S. abortions involved pills in 2020, up from 39% in 2017.

Two pills commonly used together for medication abortions are mifepristone, which, taken first, blocks hormones that support a pregnancy, and misoprostol, which then causes the uterus to empty. According to the FDA, medication abortions are safe until 10 weeks into pregnancy.

Surgical abortions conducted during the first trimester of pregnancy typically use a suction process, while the relatively few surgical abortions that occur during the second trimester of a pregnancy typically use a process called dilation and evacuation, according to the UCLA School of Medicine.

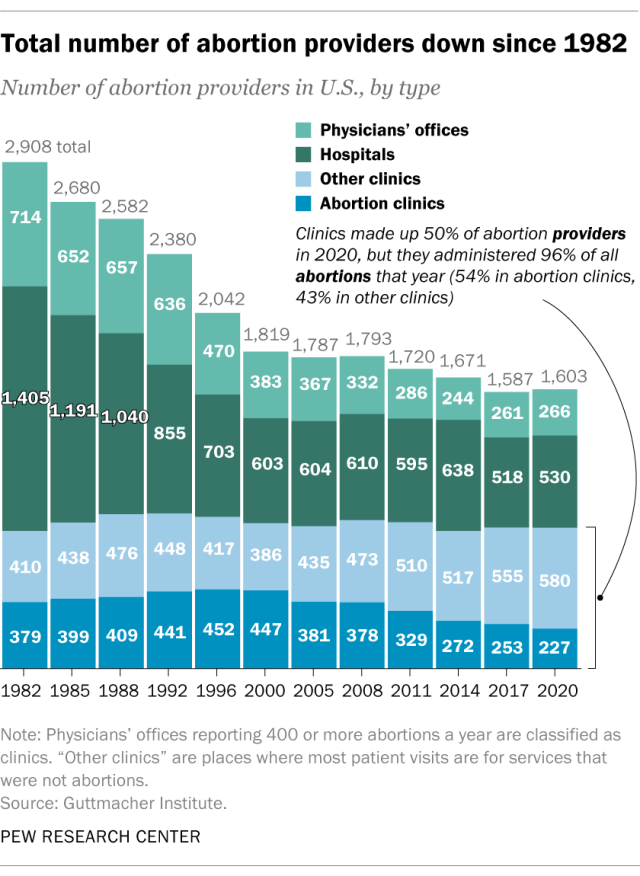

In 2020, there were 1,603 facilities in the U.S. that provided abortions, according to Guttmacher . This included 807 clinics, 530 hospitals and 266 physicians’ offices.

While clinics make up half of the facilities that provide abortions, they are the sites where the vast majority (96%) of abortions are administered, either through procedures or the distribution of pills, according to Guttmacher’s 2020 data. (This includes 54% of abortions that are administered at specialized abortion clinics and 43% at nonspecialized clinics.) Hospitals made up 33% of the facilities that provided abortions in 2020 but accounted for only 3% of abortions that year, while just 1% of abortions were conducted by physicians’ offices.

Looking just at clinics – that is, the total number of specialized abortion clinics and nonspecialized clinics in the U.S. – Guttmacher found the total virtually unchanged between 2017 (808 clinics) and 2020 (807 clinics). However, there were regional differences. In the Midwest, the number of clinics that provide abortions increased by 11% during those years, and in the West by 6%. The number of clinics decreased during those years by 9% in the Northeast and 3% in the South.

The total number of abortion providers has declined dramatically since the 1980s. In 1982, according to Guttmacher, there were 2,908 facilities providing abortions in the U.S., including 789 clinics, 1,405 hospitals and 714 physicians’ offices.

The CDC does not track the number of abortion providers.

In the District of Columbia and the 46 states that provided abortion and residency information to the CDC in 2021, 10.9% of all abortions were performed on women known to live outside the state where the abortion occurred – slightly higher than the percentage in 2020 (9.7%). That year, D.C. and 46 states (though not the same ones as in 2021) reported abortion and residency data. (The total number of abortions used in these calculations included figures for women with both known and unknown residential status.)

The share of reported abortions performed on women outside their state of residence was much higher before the 1973 Roe decision that stopped states from banning abortion. In 1972, 41% of all abortions in D.C. and the 20 states that provided this information to the CDC that year were performed on women outside their state of residence. In 1973, the corresponding figure was 21% in the District of Columbia and the 41 states that provided this information, and in 1974 it was 11% in D.C. and the 43 states that provided data.

In the District of Columbia and the 46 states that reported age data to the CDC in 2021, the majority of women who had abortions (57%) were in their 20s, while about three-in-ten (31%) were in their 30s. Teens ages 13 to 19 accounted for 8% of those who had abortions, while women ages 40 to 44 accounted for about 4%.

The vast majority of women who had abortions in 2021 were unmarried (87%), while married women accounted for 13%, according to the CDC , which had data on this from 37 states.

In the District of Columbia, New York City (but not the rest of New York) and the 31 states that reported racial and ethnic data on abortion to the CDC , 42% of all women who had abortions in 2021 were non-Hispanic Black, while 30% were non-Hispanic White, 22% were Hispanic and 6% were of other races.

Looking at abortion rates among those ages 15 to 44, there were 28.6 abortions per 1,000 non-Hispanic Black women in 2021; 12.3 abortions per 1,000 Hispanic women; 6.4 abortions per 1,000 non-Hispanic White women; and 9.2 abortions per 1,000 women of other races, the CDC reported from those same 31 states, D.C. and New York City.

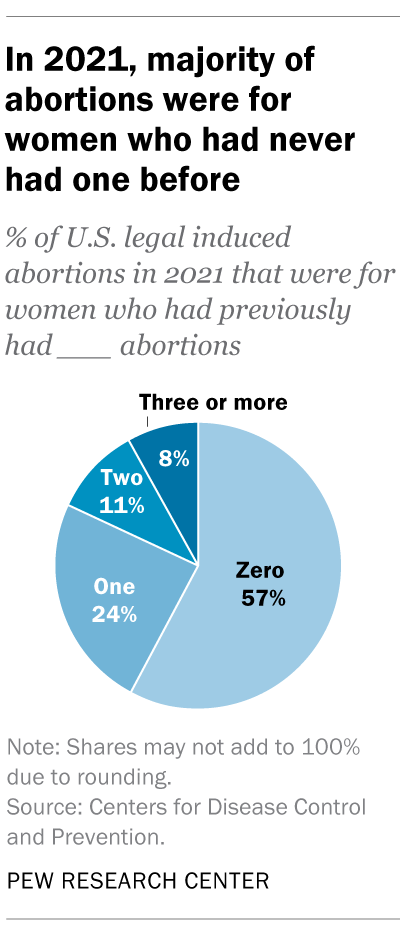

For 57% of U.S. women who had induced abortions in 2021, it was the first time they had ever had one, according to the CDC. For nearly a quarter (24%), it was their second abortion. For 11% of women who had an abortion that year, it was their third, and for 8% it was their fourth or more. These CDC figures include data from 41 states and New York City, but not the rest of New York.

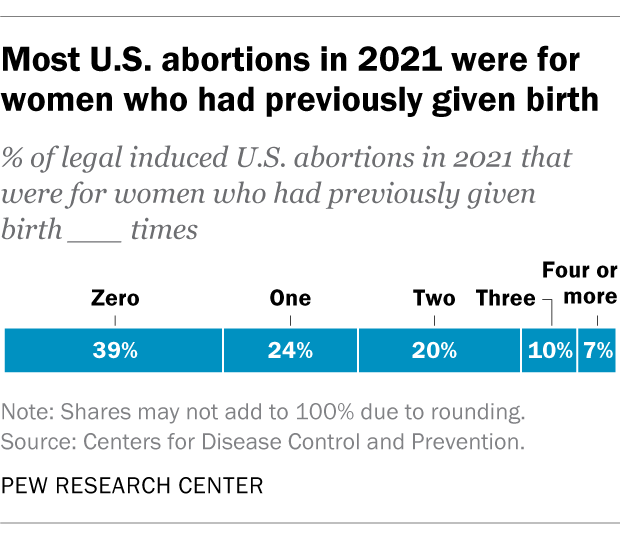

Nearly four-in-ten women who had abortions in 2021 (39%) had no previous live births at the time they had an abortion, according to the CDC . Almost a quarter (24%) of women who had abortions in 2021 had one previous live birth, 20% had two previous live births, 10% had three, and 7% had four or more previous live births. These CDC figures include data from 41 states and New York City, but not the rest of New York.

The vast majority of abortions occur during the first trimester of a pregnancy. In 2021, 93% of abortions occurred during the first trimester – that is, at or before 13 weeks of gestation, according to the CDC . An additional 6% occurred between 14 and 20 weeks of pregnancy, and about 1% were performed at 21 weeks or more of gestation. These CDC figures include data from 40 states and New York City, but not the rest of New York.

About 2% of all abortions in the U.S. involve some type of complication for the woman , according to an article in StatPearls, an online health care resource. “Most complications are considered minor such as pain, bleeding, infection and post-anesthesia complications,” according to the article.

The CDC calculates case-fatality rates for women from induced abortions – that is, how many women die from abortion-related complications, for every 100,000 legal abortions that occur in the U.S . The rate was lowest during the most recent period examined by the agency (2013 to 2020), when there were 0.45 deaths to women per 100,000 legal induced abortions. The case-fatality rate reported by the CDC was highest during the first period examined by the agency (1973 to 1977), when it was 2.09 deaths to women per 100,000 legal induced abortions. During the five-year periods in between, the figure ranged from 0.52 (from 1993 to 1997) to 0.78 (from 1978 to 1982).

The CDC calculates death rates by five-year and seven-year periods because of year-to-year fluctuation in the numbers and due to the relatively low number of women who die from legal induced abortions.

In 2020, the last year for which the CDC has information , six women in the U.S. died due to complications from induced abortions. Four women died in this way in 2019, two in 2018, and three in 2017. (These deaths all followed legal abortions.) Since 1990, the annual number of deaths among women due to legal induced abortion has ranged from two to 12.

The annual number of reported deaths from induced abortions (legal and illegal) tended to be higher in the 1980s, when it ranged from nine to 16, and from 1972 to 1979, when it ranged from 13 to 63. One driver of the decline was the drop in deaths from illegal abortions. There were 39 deaths from illegal abortions in 1972, the last full year before Roe v. Wade. The total fell to 19 in 1973 and to single digits or zero every year after that. (The number of deaths from legal abortions has also declined since then, though with some slight variation over time.)

The number of deaths from induced abortions was considerably higher in the 1960s than afterward. For instance, there were 119 deaths from induced abortions in 1963 and 99 in 1965 , according to reports by the then-U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, a precursor to the Department of Health and Human Services. The CDC is a division of Health and Human Services.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published May 27, 2022, and first updated June 24, 2022.

Jeff Diamant is a senior writer/editor focusing on religion at Pew Research Center .

Besheer Mohamed is a senior researcher focusing on religion at Pew Research Center .

Rebecca Leppert is a copy editor at Pew Research Center .

Cultural Issues and the 2024 Election

Support for legal abortion is widespread in many places, especially in europe, public opinion on abortion, americans overwhelmingly say access to ivf is a good thing, broad public support for legal abortion persists 2 years after dobbs, most popular.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 02 January 2024

Psychological traits and public attitudes towards abortion: the role of empathy, locus of control, and need for cognition

- Jiuqing Cheng 1 ,

- Ping Xu 2 &

- Chloe Thostenson 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 23 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

5473 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Social policy

In the summer of 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the historic Roe v. Wade ruling, prompting various states to put forth ballot measures regarding state-level abortion rights. While earlier studies have established associations between demographics, such as religious beliefs and political ideologies, and attitudes toward abortion, the current research delves into the role of psychological traits such as empathy, locus of control, and need for cognition. A sample of 294 U.S. adults was obtained via Amazon Mechanical Turk, and participants were asked to provide their attitudes on seven abortion scenarios. They also responded to scales measuring empathy toward the pregnant woman and the unborn, locus of control, and need for cognition. Principal Component Analysis divided abortion attitudes into two categories: traumatic abortions (e.g., pregnancies due to rape) and elective abortions (e.g., the woman does not want the child anymore). After controlling for religious belief and political ideology, the study found psychological factors accounted for substantial variation in abortion attitudes. Notably, empathy toward the pregnant woman correlated positively with abortion support across both categories, while empathy toward the unborn revealed an inverse relationship. An internal locus of control was positively linked to support for both types of abortions. Conversely, external locus of control and need for cognition only positively correlated with attitudes toward elective abortion, showing no association with traumatic abortion attitudes. Collectively, these findings underscore the significant and unique role psychological factors play in shaping public attitudes toward abortion. Implications for research and practice were discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

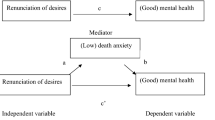

Death anxiety as mediator of relationship between renunciation of desire and mental health as predicted by Nonself Theory

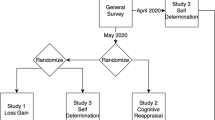

The Psychological Science Accelerator’s COVID-19 rapid-response dataset

Conservatives and liberals have similar physiological responses to threats

The U.S. Supreme Court overturned the long-time landmark ruling of Roe v. Wade in 2022 summer. Debates and legal challenges regarding legal abortion in the U.S. have been heated (Felix et al., 2023 ). Furthermore, residents in several states have or will cast their vote on a ballot measure to determine abortion rights at the state level. A Gallup poll released in 2023 summer found that about one third of voters indicated that they would only vote for a candidate who shared their views on abortion (Saad, 2023 ). Therefore, it is imperative to understand people’s attitudes toward abortion. Past research on such attitudes have mainly focused on the role of political ideology and religious belief (e.g., Hess and Rueb, 2005 ); however, to our knowledge, relatively few studies have been done to examine the psychological underpinnings. Here we propose that examining the correlations between psychological factors and attitudes toward abortion has the potential to make contributions from the perspectives of both research and practice.

First, compared to attitudes in everyday life such as attitudes toward a product or brand, attitudes toward abortion are unique because it often elicits strong emotional response and conflict experience (Foster et al., 2012 ; Scott, 1989 ). Moreover, such an attitude goes beyond individual preference as it is deeply intertwined with one’s moral and religious beliefs, cultural background, and societal norms. Debate on abortion is not merely about a personal choice; it is about the definitions of life, rights, and autonomy (Osborne et al., 2022 ; Scott, 1989 ). For abortion, the contrasting views may lead to polarized opinions. In contrast, disagreements about a product or brand preference are typically less emotionally charged and do not carry the same societal weight. Therefore, given the unique nature of attitudes toward abortion as described above, it remains unclear whether psychological factors that correlate with attitudes in other areas still apply and, if so, in what capacity they do so. Additionally, as introduced below, several studies in this area employed a qualitative approach (interview). While the qualitative approach offered valuable insights into individuals’ perspectives on abortion, we aim to expand upon these findings by employing a quantitative approach. Especially, the quantitative approach allows us to explore the unique relationship between psychology and abortion attitudes after statistically controlling for other powerful factors like religious belief and political ideology. Together, a major goal of the present study is to provide initial empirical evidence for the correlations between attitudes toward abortion and certain psychological factors. We will further detail how our study might fill research gaps when introducing specific psychological factors as described below.

Second, examining the correlations between psychological factors and attitudes toward abortion may also offer practical insights. Consider the role of thinking style, for instance. The decision to pursue an abortion is imperative and often a prominently salient one, impacting not just the pregnant woman but also her family and extensive social network. Such a decision is complex and challenging due to intense feelings (e.g., conflict) and the balance between a woman’s bodily autonomy and fetal rights. From this viewpoint, there might be a correlation between attitudes toward abortion and one’s thinking style, especially their willingness to address complex and difficult issues. Past research has highlighted the connection between rational decision-making and the availability of relevant information (Shafir and LeBoeuf, 2002 ). Hence, to facilitate informed decisions, comprehensive knowledge about abortion is both essential and beneficial. The present study will examine the relationship between thinking style and abortion attitudes. Should a correlation be identified, our study would suggest individuals engage more deeply in critical thinking about the issues of abortion to enhance abortion-related education and informed decision-making.

Together, the present study aims to shed more light on the unique role of psychology in abortion attitudes, particularly in the presence of political ideology and religious belief. Specifically, we choose to examine the factors of empathy, locus of control, and thinking style (need for cognition) based on three considerations. Firstly, from a face validity perspective, the psychological constructs are predicted to exhibit a relationship with abortion attitudes. For example, the internal locus of control aligns well with the pro-choice mantra, ‘my body, my choice. Secondly, as detailed below, although these constructs have been explored in previous studies, they have only received limited attention and their relations with abortion attitudes remain inconclusive. Hence, our study aims to fill the gaps from past research by further clarifying their roles in attitudes toward abortion. Thirdly, research has indicated significant intersections between elements like cognitive style, empathy, and locus of control with various decisions, especially in health contexts (Marton et al., 2021 ; Pfattheicher et al., 2020 ; Xu and Cheng, 2021 ). These elements are tied to motivation, information analysis, and make trade-offs (Fischhoff and Broomell, 2020 ). Building on this, our study seeks to explore the applicability of these factors to the deeply sensitive and polarizing decision of abortion. On the other hand, it is worth noting that the psychological factors examined in our study are not exhaustive or driven by theoretical considerations. However, as mentioned in recent publications (Osborne et al., 2022 ; Valdez et al., 2022 ), past research on abortion attitudes with a psychological perspective is still limited. Therefore, our hope is that the present study could provide initial yet meaningful empirical evidence to exhibit the sophisticated role of psychology in attitudes toward abortion. We detail our rationales for each factor below.

Empathy refers to a variety of cognitive and affective responses, including sharing and understanding, toward others’ experiences (Pfattheicher et al., 2020 ). Previous studies have demonstrated a positive association between empathy and prosocial behaviors, such as caring for others (Moudatsou et al., 2020 ; Klimecki et al., 2016 ), as well as a reduction in conflict and stigma (Batson et al., 1997 ; Klimecki, 2019 ). Recently, Pfattheicher et al. ( 2020 ) also demonstrated that inducing empathy for the vulnerable people could promote taking preventative measures during the Covid-19 pandemic. While researchers advocated for incorporating empathy into abortion-related mental health intervention (Brown et al., 2022 ), the role of empathy in attitudes toward abortion remains understudied. Hunt ( 2019 ) investigated the impact of empathy toward pregnant women by presenting testimonial videos in which a pregnant woman described the challenges she faced due to legal abortion restrictions in Arkansas. However, this manipulation did not significantly reduce participants’ support for the abortion restrictions. Research has found that people’s views on abortion tends to be stable over time (Jelen and Wilcox, 2003 ; Pew Research Center, 2022 ). Hence, a short video used in Hunt ( 2019 ) might not be able to change people’s long-held views on abortion. Instead, we here hypothesize that the pre-existing but not temporality induced empathy play a role in abortion attitudes.

Furthermore, in addition to the empathy toward pregnant woman, it is also reasonable to assume that (some) people may feel empathy toward the unborn. For instance, interviews with Protestant religious leaders exhibited empathy toward both pregnant women and unborn (Dozier et al., 2020 ). Embree ( 1998 ) asked participants to indicate their opinions when responding to different scenarios of abortion. As a result, the study found that 64% and 17% of participants showed a moderate and strong level of empathy for the unborn, respectively. Despite the informative findings, the relationship between attitudes toward abortion and empathy toward the unborn remains unclear, particularly when taking empathy toward pregnant woman and other factors (e.g., political ideology) into account.

Together, we raise three hypotheses regarding the role of empathy as shown below.

H1a: Empathy toward pregnant woman and unborn can coexist.

H1b: People’s empathy toward pregnant woman are positively related to the support toward abortion.

H1c: People’s empathy toward unborn are negatively related to the support toward abortion.

As empathy has been highlighted in the intervention process when dealing with abortion-related mental health issues (Brown et al., 2022 ; Whitaker et al., 2015 ), we hope our findings could generate implications for future research and practice.

Locus of control

Locus of control (LOC) refers to people’s beliefs regarding whether their life outcomes are controlled and determined by their own (internal LOC) or external resources (fate, chance and/or powerful people, external LOC) (Levenson, 1981 ). Before delving into details, it is important to note that the internal and external LOC refer to different dimensions and are not mutually exclusive (Levenson, 1981 ; Reknes et al., 2019 ). For example, a person’s success may be determined by both hardworking and support from others. Regarding abortion attitudes, Sundstrom et al. ( 2018 ) analyzed interview contents and found that some women’s thoughts on pregnancy and abortion aligned with an internal locus of control (e.g., “As women, we need to take control as much as possible of our reproductive health”), while others aligned with an external locus of control (e.g., “leave it in God’s hands…we’ll just play it by ear and if I get pregnant, I get pregnant”).

The findings from Sundstrom et al. ( 2018 ) were informative and consistent with common sense. For example, at face value level, the slogan of “my body my choice” well aligns with the concept of internal LOC. However, the role of internal LOC in abortion attitudes may be more complicated. That is, religious belief may complicate the association between internal LOC and abortion attitudes. Past studies, including a meta-analysis and a study with over 20,000 participants, found a positive relationship between internal LOC and religious belief (Coursey et al., 2013 ; Falkowski, 2000 ; Iles-Caven et al., 2020 ). As noted in these articles, there are similarities between internal LOC and religious belief. For instance, religious beliefs often provide individuals with a sense of meaning, purpose, and guidance in life. Meanwhile, people higher in internal LOC are more likely to report higher levels of existential well-being and purpose in life, which can be associated with religious belief and engagement (Kim-Prieto et al., 2005 ; Krause and Hayward, 2013 ). Thus, the relationship between internal LOC and religious belief may complicate how internal LOC is involved in the abortion attitudes. Sundstrom et al. ( 2018 ) used interviews to explore the role of LOC in thoughts about abortion. However, this method might not sufficiently differentiate the influence of religious beliefs. In this study, we adopt a quantitative approach, using a classical scale to measure LOC. We aim to empirically assess the relationship between internal LOC and attitudes toward abortion, especially when accounting for religious belief. Furthermore, considering that the relationship between internal LOC and abortion attitudes might be intertwined with religious beliefs, we refrain from positing a specific hypothesis at this point.

External LOC, on the other hand, does not appear to have a significant relationship with religious belief. Additionally, a few studies found that people higher in external LOC tended to attribute outcomes to external reasons (Falkowski, 2000 ; Reknes et al., 2019 ). Building on this concept, individuals with a higher external locus of control (LOC) may be more inclined to attribute pregnancy to external factors and place less emphasis on personal responsibility. Accordingly, we predict the hypothesis below.

H2: External LOC will be positively related to the support toward abortion.

Need for cognition

Based on face validity, thinking style might pertain to one’s perception of abortion. For instance, individuals who prioritize comprehensive and empirical data might arrive at a different conclusion than those who lean on personal stories and emotional narratives. A few studies have tapped into the relationship between thinking style and attitudes toward abortion. Valdez et al. ( 2022 ) conducted qualitative interviews on abortion and employed natural language processing techniques to analyze the interviews. The study identified analytical thinking, which involved considering abortion from multiple perspectives, had a negative relationship with the number of cognitive distortions (such as polarized and rigid thinking about abortion). However, such a finding conflicted with another study by Hill ( 2004 ) where the concept of cognitive complexity (thinking beyond surface-level observations) did not correlate with attitudes toward abortion. The inconsistency might be due to methodological issues. For example, the correlations described above in Valdez et al. ( 2022 ) were derived from a small sample consisting of 16 participants. A low reliability of the cognitive complexity scale used in Hill ( 2004 ) might (partly) address the non-significant relationship. Thus, the present study will utilize the Need for Cognition scale, a widely recognized and validated instrument that measures thinking style, to examine its correlation with attitudes toward abortion in a larger sample.

Need for cognition (NFC) pertains to the inclination to derive satisfaction from and actively participate in effortful thinking (Cacioppo et al., 1984 ). Consistent with its concept, past research demonstrated that NFC was positively correlated with information seeking (Verplanken et al., 1992 ), academic achievement (Richardson et al., 2012 ), and logical reasoning performance (Ding et al., 2020 ). As for attitudes toward abortion, we hypothesize the following.

H3: There will be a positive correlation between NFC and attitudes toward abortion.

Our prediction is based on two reasons. First, NFC drives individuals to actively seek and update information and knowledge. It was discovered that acquiring a deeper understanding of abortion correlated with increased support for it (Hunt, 2019 ; Mollen et al., 2018 ). Second and relatedly, NFC was found to be negatively associated with various stereotype memories and positively related to non-prejudicial social judgments (Crawford and Skowronski, 1998 ; Curşeu and de Jong, 2017 ).

In sum, the present study aims to provide empirical evidence for the association between attitudes toward abortion and psychology by examining and clarifying the role of empathy, locus of control, and need for cognition. Past research has repeatedly found the involvement of political ideology and religious belief in abortion attitudes (e.g., Hess and Rueb, 2005 ; Holman et al., 2020 ; Jelen, 2017 ; Osborne et al., 2022 ; Prusaczyk and Hodson, 2018 ). Given their powerful and robust effect, it is crucial to gather additional empirical evidence to elucidate the distinct contribution of psychology to attitudes toward abortion, while considering the influence of political ideology and religious beliefs. Additionally, when describing attitudes toward abortion, the dichotomization of “pro-choice” and “pro-life” have been widely used for decades. However, some studies have criticized that the dichotomization oversimplified attitudes toward abortion (Hunt, 2019 ; Osborne et al., 2022 ; Rye and Underhill, 2020 ). That is, people’s views on abortion vary across different scenarios and reasons. For instance, people showed less support toward abortion with elective reasons than with traumatic reasons (Hoffmann and Johnson, 2005 ). With confirmatory analysis, Osborne et al. ( 2022 ) derived two types of abortion: traumatic (e.g., pregnancy due to rape) vs. elective (e.g., the woman does not want the child anymore). Building on prior research, the current study aims exploring potential variations in attitudes across different abortion reasons. Furthermore, we also intend to examine whether the psychological factors described above have varying associations with different types of abortion.

Participants

The study was approved by IRB before data collection. Participants were recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk (mTurk) on October 20th, 2022. To be eligible for the study, participants must be an adult, a U.S. citizen, and have an approval rating greater than 98% in mTurk. A total of 300 participants were enrolled into the study. Each participant received $3 for compensation. Six participants did not complete at least 80% of the items and were removed from the study. Thus, the effective sample size was 294. Demographics are presented in the Results section.

Materials and procedures

Participants took an online survey developed by Qualtrics. Our study did not set a specific time restriction. Across 294 participants, the average survey completion time was 682.8 s (SD = 286.6 s). The median completion time was 595.0 s (IQR = 344.8 s). The following questionnaires were completed.

Attitudes toward abortion

Hoffmann and Johnson ( 2005 ) and Osborne et al. ( 2022 ) analyzed attitudes toward abortion with six different scenarios (scenarios a-f below) that were measured by the U.S. General Social Survey. We further added an additional item regarding underage pregnancy for two reasons. First, compared to other Western industrialized nations, the U.S. has historically had a higher rate of underage pregnancies. Additionally, underage pregnant individuals tended to have a higher likelihood of seeking abortions compared to their older counterparts (Lantos et al., 2022 ; Kearney and Levine, 2012 ; Sedgh et al., 2015 ). Second, underage pregnancy is linked to various adverse outcomes, such as increased risk during childbirth, heightened stress and depression, disruptions in education, and financial challenges (Eliner et al., 2022 ; Hodgkinson et al., 2014 ; Kearney and Levine, 2012 ). Given the significance and prevalence of underage pregnancy, we chose to include it as a scenario to understand the public’s perception. Additionally, we understood that people might feel conflict or uncertain toward one or more scenarios. Hence, instead of using binary response (yes/no format) adopted in the U.S. General Social Survey, we employed a 1 to 7 Likert scale for each scenario, with a higher score indicating stronger support for a pregnant woman to obtain legal abortion.

The seven scenarios in the present study included: (a) there is a strong chance of serious defect in the baby; (b) the woman’s own health is seriously endangered by the pregnancy; (c) the woman became pregnant as a result of rape; (d) the woman is married and does not want any more children; (e) the family has a very low income and cannot afford any more children; (f) the woman is not married and does not want to marry the man; and (g) the woman is underage.

Following the wording used to measure empathy in Pfattheicher et al. ( 2020 ), we developed six items to measure the empathy toward the pregnant woman and unborn or fetus, respectively. The scale of empathy toward pregnant woman included: (a) I am very concerned about the pregnant woman who may lose access to legal abortion; (b) I feel compassion for the pregnant women who may lose access to legal abortion; and (c) I am quite moved by the pregnant women who may lose access to legal abortion. The scale of empathy toward unborn included: (a) I am very concerned about the fetus or unborn child; (b) I feel compassion for the fetus or unborn child; and (c) I am quite moved by the fetus or unborn child. Participants rated each item on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 being strongly disagree and 5 being strongly agree. Thus, a higher score demonstrated stronger empathy toward the target. The Cronbach’s α for the scale of toward pregnant woman was 0.90 in the present study. The Cronbach’s α for the scale of toward unborn was 0.92.

The need for cognition scale (NFC, Cacioppo et al., 1984 ) intends to measure the tendency to engage into deep thinking. It has 18 items, such as “I only think as hard as I have to” and “I find satisfaction in deliberating hard and for long hours”. Participants rated each item on a five-point Likert scale, with a higher score indicating a greater tendency to enjoy deep thinking. In the present study, the reliability of this scale was 0.93.

The present study adopted Levenson multidimensional locus of control scale (Levenson, 1981 ). Across 24 items, this scale measures three dimensions of locus of control: internality (sample item: Whether or not I get to be a leader depends mostly on my ability); powerful others (sample item: I feel like what happens in my life is mostly determined by powerful people); and chance (sample item: To a great extent my life is controlled by accidental happenings). In the present study, participants rated each item on a 1 to 6 Likert scale, with a higher score indicating a stronger belief that fate was controlled by self, powerful others, or chance. The Cronbach’s α for the subscales of internality, powerful others, and chance was 0.84, 0.91, and 0.93, respectively. As shown below, there was a high agreement between powerful others and chance subscales ( r = 0.87, p < 0.001). Hence, we combined these two subscales to form an external locus of control composite.

Demographics

After completing the scales described above, participants were asked to report their demographic information including race, age, gender, education, annual household income, current relationship status, abortion experience, religious belief, and political ideology. Gender was coded with 1 = male, 2 = female, and 3 = other. Race was coded with 1 = White or Caucasian, 2 = Hispanic or Latinx, 3 = Black or African American, 4 = Asian or Asian American, and 5 = Other. Education was coded with six levels: 1 = Less than high school graduate, 2 = High school graduate or equivalent, 3 = Some college or associate degree, 4 = Bachelor’s degree, 5 = Master’s degree, 6 = Doctoral degree. Annual household income was categorized into 13 levels and ranged between under $9,999 and above $120,000 with increments of $9,999. Current relationship status was coded into six levels: 1 = single and not dating, 2 = single but in a relationship, 3 = married, 4 = divorced, 5 = widowed, 6 = other. For abortion experience participants were asked “For any reason, have you had an abortion?”. For this question, the answer was coded with 1 = yes and 2 = no.

Religious belief was measured with three items. The first item asked “How often do you attend religious services?” Participants selected one option out of the following: 1 = never, 2 = a few times per year, 3 = once a month, 4 = 2–3 times a month, 5 = once a week or more. The second item asked “How important is religion to you personally?” Participants rated this question on a five-point Likert point, with 5 being most important. The third question asked “How would you describe your religious denomination”. The options included 1 = Christian, 2 = Islam, 3 = Judaism, 4 = Buddhism, 5 = Hinduism, 6 = other or atheism. In the present study, the first two items were highly correlated ( r = 0.77, p < 0.001). Following Hunt ( 2019 ), we combined the two items to form a general religiosity composite, with a higher score indicating a stronger religious belief.

Political ideology was measured with two items: (a) Generally, how would you describe your views on most social political issues (e.g., education, religious freedom, death penalty, gender issues, etc.)? and (b) Generally, how would you describe your views on most economic political issues (e.g., minimum wage, taxes, welfare programs, etc.)? Participants rated each item with a five-point Likert scale, with 1 = strongly conservative 2 = conservative 3 = moderate 4 = liberal 5 = strongly liberal. We found a strong correlation between the two political ideology items, r = 0.76, p < 0.001. Hence, we combined the two items to form a general political ideology composite.

SPSS 24.0 was employed to perform all the analyses. Across 294 participants, age ranged from 21 to 79, with a mean of 40.4 and a standard deviation of 12.4. Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics for the variables of gender, race, education, annual household income, current relationship status, religious denomination, and abortion experience.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of attitudes toward abortion in different scenarios, religious belief, political ideology, and the scores of the psychological scales. Similar to the results obtained from the large-scale surveys in the U.S. and New Zealand (Osborne et al., 2022 ), the support toward abortion was strong (neutral = 4) across all scenarios.

To examine the structure of attitudes toward abortion in different scenarios, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with a Varimax orthogonal rotation was performed on all seven scenarios. With eigenvalue ≥ 1 as the threshold, two components were generated, accounting for 81.34% of the variability. Table 3 presents the PCA results. As shown, we obtained two distinct components. The first one included the scenarios of baby defection, pregnant woman’s health being endangered, pregnancy caused by rape, and underage pregnancy. The second component included the scenarios of not wanting the child, low income, and not wanting to marry. Such a differentiation between the two components was consistent with the notion in Osborne et al. ( 2022 ). Following this paper and the face validity of the scenarios, we labeled the two components traumatic abortion and elective abortion, respectively. Accordingly, we also computed a composite score for each component by averaging the corresponding items. In line with previous research (Hoffmann and Johnson, 2005 ), the support was significantly stronger toward the traumatic abortion (mean = 5.84, SD = 1.24) than the elective abortion (mean = 4.94, SD = 1.74), t (293) = 11.51, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.67.

Table 4 presents the zero-order correlations between attitudes toward traumatic and elective abortions, demographics, and scores of the psychological factors. Consistent with the findings from past research (e.g., Hess and Rueb, 2005 ; Holman et al., 2020 ), a stronger religious belief was negatively related to the support toward both types of abortions. A stronger liberal ideology was positively related to the support toward both types of abortions. Additionally, empathy toward the pregnant woman was positively associated with the support toward both types of abortions whereas empathy toward unborn or fetus had an opposite effect. Based on the zero-order correlation, we did not find a significant relationship between internal locus of control and attitudes toward either type of abortion. The external locus of control (either powerful others or chance), on the other hand, was positively related to the support toward elective but not traumatic abortion. As there was a high agreement between the two external locus of control subscales ( r = 0.87, p < 0.001), we formed a general external locus of control composite by averaging the two items in the following regressions. Finally, need for cognition was positively related to attitudes toward elective abortion but not traumatic abortion.

While the zero-order correlations were informative, we were mindful that the Type I error might be greatly inflated due to a vast amount of repeated testing. Moreover, one goal of the study was to examine the role of psychological factors in the presence of religious belief and political ideology. Thus, we performed a hierarchical linear regression on each type of abortion, with age, gender, income, and education in the first block, religious belief and political ideology in the second block, and psychological factors in the third block. We separated the regression between the two types of abortion because the role of predictors might vary. This approach was also employed in Osborne et al. ( 2022 ). Table 5 exhibits the regression results.

As shown in Table 5 , the demographic variables of age, gender, education, and income did not account for a significant portion of the variability in attitudes toward either type of abortion. The present study added to the literature that there might not necessarily be a difference in attitudes toward abortion between males and females (Bilewicz et al., 2017 ; Jelen and Wilcox, 1997 ). By contrast, in the second block, religious belief and political ideology collectively explained a sizable portion of the variability in attitudes toward both types of abortion. In block 3, in the presence of demographic variables including religious belief and political ideology, psychological factors could still account for a significant portion of the variability.

Looking at the individual psychological predictors (for more detailed interpretations please refer to the discussion part), consistent with our hypothesis, empathy toward the pregnant woman was positively associated with the support toward both types of abortion. By contrast, empathy toward the unborn or fetus was negatively associated the support toward abortion. For the factor of locus of control, the internal locus of control was not related to any type of abortion attitudes when zero-order correlation was used (Table 4 ); yet it was positively related to abortion attitudes after all other predictors were taken into account, indicating a suppressing effect. Upon further examination, we identified two suppressors: religious belief and empathy toward the unborn. After removing these two variables, internal locus of control was no longer significant. The observed pattern reflected our previous prediction, indicating that the role of internal locus of control could be complicated by religious beliefs. External locus of control, on the other hand, was positively correlated with the support toward elective abortion. Similarly, need for cognition (NFC) also had a positive relationship with the support toward elective abortion. Neither external locus of control nor NFC had a significant correlation with attituded toward traumatic abortion. Hence, our hypotheses regarding external locus of control and NFC were partially supported. We detailed out interpretation and discussion of the results below.

The present study aimed to provide empirical evidence for the correlations between psychological factors and attitudes toward abortion. As introduced earlier, while it is common to find the involvement of psychology in everyday life attitudes and preferences, attitudes toward abortion are unique and drastically different. Given its unique nature, it lacks empirical evidence regarding whether psychological factors that interplay with attitudes in other areas still apply and, if so, in what capacity they do so. Past research has primarily focused on the role of religious belief and political ideology. Our study demonstrated a substantial involvement ( R 2 change = 0.27 and 0.24 for traumatic and elective abortion, respectively) of the psychological factors, after controlling for religious belief and political ideology. More importantly, these effects were comparable to the variability accounted for by religious belief and political ideology combined, particularly in the elective abortion category. The results highlighted the influential role of psychological factors in shaping attitudes toward abortion.

Additionally, past research has shown the interconnection between psychology and the public’s attitudes toward major societal events. For example, during the Covid-19 pandemic, while the perception of mask-wearing and/or social distancing was highly politicized, studies found that attitudes toward these preventative measures to be related to thinking style, self-control, numeracy, and working memory capacity (Steffen and Cheng, 2023 ; Xie et al., 2020 ; Xu and Cheng, 2021 ). In line with this, our study further underscored the significant influence of psychology on another pressing societal topic: abortion. In the sections below, we detail our findings and relevant implications. We are fully aware that our study was preliminary and hope it could serve as a starting point for future research and practice. We also acknowledge the limitations of our study and address them at the end.

Some past studies on empathy and abortion only considered the empathy toward the pregnant woman (e.g., Brown et al., 2022 ; Homaifar et al., 2017 ; Hunt, 2019 ; Whitaker et al., 2015 ). The present study identified two types of empathy when dealing abortion: empathy toward the pregnant woman and empathy toward the unborn. In the presence of each other, we found that greater empathy toward the pregnant woman was associated with more support toward abortion, whereas greater empathy toward the unborn or fetus was associated with less support toward abortion. Such a pattern suggested that empathy might be a source of conflict feeling. That is, when considering abortion, concerns and care toward pregnant woman and unborn could coexist, potentially leading to conflict and dilemma when people thought about abortion. While the present study examined the public’s attitudes toward abortion with a diverse sample, pregnant women might have a similar pattern of empathy and hence feel conflict and dilemma when thinking about abortion. To cope with such a conflict, it might be beneficial for a counselor to acknowledge conflicting emotions that arise from empathizing with both the unborn and the pregnant individual. Moreover, the counselor could guide the client through the process of reconciling these emotions to alleviate feelings of isolation or confusion the client may experience. Future research in the realms of mental health and counseling should consider integrating these dual empathy perspectives and empirically assess the efficacy of such therapeutic interventions.

Additionally, Hunt ( 2019 ) did not find a significant influence of empathy on abortion attitudes change when participants were exposed to testimonial videos featuring pregnant women discussing the legal obstacles they faced. The disparity between Hunt’s ( 2019 ) findings and our own could potentially be attributed to the inherent stability and longstanding nature of abortion attitudes. Research has found that people’s views on abortion tends to be stable over time (Jelen and Wilcox, 2003 ; Pew Research Center, 2022 ). As a result, it is possible that pre-existing empathy, rather than empathy induced temporarily, was the factor correlated with individuals’ perception and consideration of abortion. Our findings were consistent with this possibility. Together, our findings supported H1a to H1c. Moreover, our study shed more light on empathy by showing its association with distinct views on abortion. The results suggest that future research could investigate how different types of empathy are formed and how they influence the shaping and persuasion of abortion attitudes.

Through qualitative interviews, Sundstrom et al. ( 2018 ) unveiled individual differences in the locus of control when discussing opinions on abortion. However, these interviews might not have fully captured the interplay between internal and external locus of control and other factors involved attitudes toward abortion. To fill the gap, our study employed a quantitative approach to delve deeper into how locus of control correlated with abortion attitudes. Consistent with Levenson ( 1981 ) and Reknes et al. ( 2019 ), we found that the constructs internal locus of control and external locus of control were differentiated but not unidimensional. For internal locus of control, interestingly, we found a suppressing effect. As discussed earlier, the role of internal locus of control in abortion attitudes might be complicated. That is, on the one hand, by face validity, the internal locus of control well aligned with the concept of “my body, my choice” (Sundstrom et al., 2018 ). On the other hand, in line with past research (Coursey et al., 2013 ; Falkowski, 2000 ; Iles-Caven et al., 2020 ), our study found that internal locus of control was positively related to religious belief. Furthermore, as shown in Table 4 , internal locus of control was also positively related to the empathy toward the unborn, and such a relationship was significantly mediated by religious belief (mediation effect = 0.21, SE = 0.5, 95% CI = [0.13, 0.31]). Therefore, when using zero-order correlation, the effect of internal locus of control might be neutralized by the two opposite parts (“my body, my choice” vs. religious belief) discussed above. By contrast, in regression, the “my body, my choice” part stood out because the religiosity part was partialled out by the variables of religious belief and empathy toward the unborn.

In addition to internal locus of control, we also discovered that external locus of control was involved in abortion attitudes. Specifically, we found a positive relationship between external locus of control and support toward elective abortion (H2 was partially supported). Past research has found that locus of control is related to attribution (Falkowski, 2000 ; Reknes et al., 2019 ). Thus, our finding was in line with the notion that those with a greater level of external locus of control might be more likely to attribute unwanted pregnancy to external reasons (not personal responsibility), and hence showed more support toward abortion.

Our findings regarding locus of control suggest that individuals might simultaneously believe in personal autonomy (“my body, my choice”) while also feeling that certain life events, like unwanted pregnancies, are influenced by external factors beyond their control. This is particularly true when thinking about elective abortion. Education and counseling practices might be designed to reflect this duality. For example, materials and discussions could simultaneously emphasize the importance of personal choices and responsibilities, while also exploring societal, cultural, or circumstantial factors that might influence abortion decision. Incorporating both perspectives would allow to create a supportive environment where individuals feel seen and acknowledged in their complexities.

As introduced earlier, past research on the relationship between thinking style and abortion attitudes was inconclusive. To clarify the relationship, the present study adopted the validated need for cognition scale. Need for cognition has demonstrated its involvement in consequential events, such as political elections and the adoption of preventive measures during the Covid-19 pandemic (Sohlberg, 2019 ; Xu and Cheng, 2021 ). In the present study, we discovered that need for cognition was positively related to the support toward elective abortion. Such a finding was consistent with the notion that need for cognition was negatively related to stereotypes (Crawford and Skowronski, 1998 ; Curşeu and de Jong, 2017 ). Additionally, as need for cognition drives individuals to seek and update knowledge, our result was also in line with the finding that gaining knowledge about abortion led to more positive view on abortion (Hunt, 2019 ; Mollen et al., 2018 ). Our study implied that future research could empirically evaluate if indeed abortion knowledge mediates the relationship between need for cognition and abortion attitudes.

It is worth noting that the present study also clarified the role of need for cognition in attitudes toward abortion by examining a potential artifact. Specifically, the observed positive relationship between need for cognition and support for abortion might be an artifact, given that liberal ideology is positively correlated with both abortion attitudes and need for cognition (Young et al., 2019 ). However, as shown in our regression, the relationship between need for cognition and elective abortion remained significant in the presence of other variables, including political ideology. Thus, the finding suggested that at least part of the relationship between need for cognition and attitude toward abortion was unique and not driven by political ideology.

Our findings related to need for cognition had an implication on abortion-related education. As discussed earlier, having adequate knowledge about abortion could facilitate the support for making informed decisions. As need for cognition was found to be related to openness and motivation to seek and update information (Russo et al., 2022 ), our finding suggested that cultivating willingness to engage into critical thinking might be beneficial for education on abortion and reproductive rights. While we are fully aware that correlation does not equate to causation, our study still offers a starting point for future research and practice on abortion-related education.

Traumatic abortion vs. elective abortion

While some researchers argued that the dichotomization of “pro-choice” and “pro-life” was oversimplified, to date, only two studies have empirically examined attitude variation between different abortion scenarios (Hoffmann and Johnson, 2005 ; Osborne et al., 2022 ). Both studies demonstrated that public views on abortion can be grouped into two categories: traumatic and elective. Our research not only replicated these findings but also introduced two significant advancements. First, we incorporated a scenario addressing underage pregnancy, given its high prevalence and significance. Secondly, instead of a binary response, we employed a 7-point Likert scale, allowing us to more accurately capture potential conflicting attitudes among participants.

Furthermore, our findings revealed that the roles of external locus of control and need for cognition varied in relation to attitudes toward the two types of abortion. Interestingly, we observed that neither of these variables significantly related to attitudes toward traumatic abortion, as indicated by both zero-order correlation and regression analyses. Conceptually, the scenarios of traumatic abortion (e.g., pregnancy caused by rape; mother life endangered) tend to be more extreme and emergent than the scenarios of elective abortion. Hence, there might be less room for psychological factors, such as thinking or attribution, to function in traumatic abortion than in elective abortion. Our interpretation was also consistent with the statistical pattern between the two abortions. That is, compared to elective abortion, the standard deviation of traumatic abortion was smaller. Additionally, there were more participants rated seven on the Likert scale in the scenarios of traumatic abortion (29.6%) than in the scenarios of elective abortion (18%). Despite the difference between the two types of abortion, it is essential to acknowledge that elective abortion does not imply a stress-free experience. Both traumatic and elective abortions involve significant levels of stress and emotional challenges. While traumatic abortion scenarios can be considered more extreme, it is crucial to recognize that individuals undergoing elective abortion may also experience considerable emotional distress.

Taken together, with concrete evidence, our study demonstrated that the public’s attitude toward abortion depended on abortion reasons. Our study also implied that future research should focus on attitudes toward specific abortion scenarios rather than a holistic concept of abortion. Furthermore, the differentiation between the traumatic and elective abortions suggested the limitation and potential ineffectiveness of one-size-fits-all legislative solutions. Given the varying and often conflicting attitudes that people harbor, it would be reasonable for legislative frameworks to be flexible, adaptive, and cognizant of the different circumstances surrounding abortion. This will not only be more reflective of public opinions but also more supportive of individuals who undergo different types of abortion experiences, each of which carries its own set of emotional and psychological challenges.

Expanding findings with a quantitative approach

Some past studies employed a qualitive approach when dealing with attitudes toward abortion (e.g., Dozier et al., 2020 ; Sundstrom et al., 2018 ; Valdez et al., 2022 ; Woodruff et al., 2018 ). These investigations have provided insights and served as inspirations for our own research. However, the relationship between abortion attitudes and pertinent factors may remain somewhat opaque. This is particularly true when considering the intricate interconnectedness among these factors. The present study demonstrated that findings from qualitative studies could be extended and enriched with a quantitative approach. For instance, we utilized quantitative scales to measure empathy toward the unborn —a variable that was previously identified through interviews in the study by Dozier et al. ( 2020 ). Moreover, we further exhibited the role of empathy toward the unborn when statistically controlled other variables, including empathy toward the pregnant. Similarly, the role of internal locus of control was revealed in interviews in Sundstrom et al. ( 2018 ). With validated scales, we exhibited the correlation with internal locus of control in both types of abortion. Furthermore, by detecting and interpreting a suppressing effect, we showed the interplay between internal locus of control, religious belief, and attitude toward abortion. Thus, our study implied that using quantitative scales and analyses was a viable approach to examine attitude toward abortion and could deepen the understanding of relevant factors.

Limitations and future directions

Despite the contributions, limitations should be acknowledged as well. First and foremost, we believe our study was still in the explorative stage. The specific psychological factors tested in the present study were not exhaustive and not theoretically driven. We hope the present study could provide initial empirical evidence to show the sophisticated role of psychology in attitudes toward abortion. Future studies could use a more theoretical driven approach to examine the specific psychological involvement in abortion attitudes. For example, given the correlation between need for cognition and attitudes toward abortion, future research could further elucidate the role of thinking style in attitudes toward abortion by incorporating the Dual-Process Theory (Evans, 2008 ). The Dual-Process Theory posits that humans have two distinct systems of information processing: System 1, which is intuitive, automatic, and fast; and System 2, which is deliberate, analytical, and slower. By examining the interplay between these two systems, researchers might gain insights into how intuitive emotional responses versus more deliberate cognitive analyses influence individuals’ attitudes toward abortion. For instance, are individuals who predominantly rely on System 1 more swayed by emotive narratives or imagery related to abortion?

Second, when analyzing and discussing the results, we proposed several possible underlying mechanisms that might elucidate the relationships observed. To illustrate, we employed the concept of attribution to shed light on the role of an external locus of control, positing that individuals with a strong external locus might attribute abortion decisions to external factors or circumstances rather than personal choices. Furthermore, we suggested that the observed positive relationship between the need for cognition and abortion attitudes might be mediated through abortion knowledge. This implies that individuals with a higher need for cognition could potentially seek out more information on abortion, leading to more informed attitudes. However, while these interpretations offer potential insights, we recognize their speculative nature. It’s crucial to emphasize that our proposed mechanisms require rigorous empirical testing for validation. For example, it would be of interest to test whether indeed, gaining various types of abortion knowledge improves views of abortion.

Third, as described above, we strived to show how our findings could be potentially used in abortion-related counseling. However, we acknowledge that our study is explorative but not counseling focused. Therefore, while we believe our findings offer meaningful implications, we caution against over-extrapolating their direct applicability to counseling contexts. Future research could delve into empirically investigating how psychological factors, such as varying empathy types and loci of control, could be utilized to alleviate negative feelings associated with abortion decisions. Additionally, understanding how various psychological factors interact with cultural and social norms could further help tailor counseling approaches.

Fourth, the present study did not include an attention check item. We believe the quality of our survey could have been improved had we included one or more attention check items. However, the reliabilities of our scales were relatively high (ranged from 0.84 to 0.93). Additionally, we also replicated some major findings from previous research (e.g., the associations between attitudes toward abortion and religious belief and political ideology). Thus, we believe that overall, inattention did not affect the quality of our data. Future online surveys could consider using attention check items for quality control.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates the unique contribution of empathy, locus of control, and need for cognition to how people perceived abortion in different scenarios. The findings suggests that attitudes toward complex moral issues like abortion are shaped by individual psychological traits and cognitive needs, in addition to societal, religious, and cultural norms. Future research could use our study as a starting point to expand on these findings, exploring other psychological traits and cognitive processes that may similarly affect perceptions of abortion and other controversial subjects.

Data availability

Data included in this project may be found in the online repository, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/E5AB5R .

Batson CD, Polycarpou MP, Harmon-Jones E, Imhoff HI, Mitchener EC, Highberger L et al. (1997) Empathy and attitudes: can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group improve feelings toward the group? J Person Soc Psychol 72(1):105–118

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bilewicz M, Mikołajczak G, Babińska M (2017) Speaking about the preborn. How specific terms used in the abortion debate reflect attitudes and (de)mentalization. Person Individ Differ 111:256–262

Article Google Scholar

Brown L, Swiezy S, McKinzie A, Komanapalli S, Bernard C (2022) Evaluation of family planning and abortion education in preclinical curriculum at a large midwestern medical school. Heliyon 8(7):e09894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09894

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cacioppo JT, Petty RE, Kao CF (1984) The efficient assessment of need for cognition. J Person Assess 48(3):306–307. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4803_13

Comrey AL, Lee HB (1992) A first course in factor analysis (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc

Coursey LE, Kenworthy JB, Jones JR (2013) A meta-analysis of the relationship between intrinsic religiosity and locus of control. Arch Psychol Relig 35:347–368. https://doi.org/10.1163/15736121-12341268

Crawford MT, Skowronski JJ (1998) When motivated thought leads to heightened bias: high need for cognition can enhance the impact of stereotypes on memory. Person Soc Psycholo Bull 24(10):1075–1088. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672982410005

Curşeu PL, de Jong JP (2017) Bridging social circles: need for cognition, prejudicial judgments, and personal social network characteristics. Front Psychol 8:1251. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01251

Ding D, Chen Y, Lai J, Chen X, Han M, Zhang X (2020) Belief bias effect in older adults: roles of working memory and need for cognition. Front Psychol 10:2940. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02940

Dozier JL, Hennink M, Mosley E, Narasimhan S, Pringle J, Clarke L, Blevins J, James-Portis L, Keithan R, Hall KS, Rice WS (2020) Abortion attitudes, religious and moral beliefs, and pastoral care among Protestant religious leaders in Georgia. PloS one 15(7):e0235971. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235971

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Eliner Y, Gulersen M, Kasar A, Lenchner E, Grünebaum A, Chervenak FA, Bornstein E (2022) Maternal and neonatal complications in teen pregnancies: a comprehensive study of 661,062 patients. J Adolesc Health 70(6):922–927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.12.014

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Embree RA (1998) Attitudes toward elective abortion: preliminary evidence of validity for the personal beliefs scale. Psychol Rep 82(3 Pt 2):1267–1281. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1998.82.3c.1267

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Evans JSTBT (2008) Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment and social cognition. Ann Rev Psychol 59:255–278. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093629

Falkowski CK (2000) Locus of control, religious values, work values and social policy choices. Diss Abstracts Int. Sec B: Sci Eng 61:1694

Google Scholar

Felix., M., Sobel, L., & Salganicoff, A. (2023). Legal challenges to state abortion bans since the dobbs decision. Kaiser Family Foundation . Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/legal-challenges-to-state-abortion-bans-since-the-dobbs-decision/

Fischhoff B, Broomell SB (2020) Judgment and decision making. Ann Rev Psychol 71:331–355

Foster DG, Gould H, Taylor J, Weitz TA (2012) Attitudes and decision making among women seeking abortions at one U.S. clinic. Perspect Sexual Reprod Health 44(2):117–124. https://doi.org/10.1363/4411712

Hess JA, Rueb JD (2005) Attitudes toward abortion, religion, and party affiliation among college students. Curr Psychol 24(1):24–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-005-1002-0

Hill A (2004) The relationship between attitudes about abortion and cognitive complexity. UW-J Undergrad Res VII:1–6

ADS Google Scholar

Hodgkinson S, Beers L, Southammakosane C, Lewin A (2014) Addressing the mental health needs of pregnant and parenting adolescents. Pediatrics 133(1):114–122. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0927

Hoffmann JP, Johnson SM (2005) Attitudes toward abortion among religious traditions in the United States: change or continuity. Soc Relig 66(2):161–182. https://doi.org/10.2307/4153084

Holman M, Podrazik E, Silber Mohamed H (2020) Choosing choice: how gender and religiosity shape abortion attitudes among Latinos. J Race Ethnicity Politics 5(2):384–411. https://doi.org/10.1017/%20rep.2019.51

Homaifar N, Freedman L, French V (2017) “She’s on her own”: a thematic analysis of clinicians’ comments on abortion referral. Contraception 95(5):470–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2017.01.007

Hunt ME (2019) Shifting Abortion Attitudes using an Empathy-based Media Intervention: a randomized controlled study. graduate theses and dissertations Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3256

Jelen TG (2017) Public attitudes toward abortion and LGBTQ issues: a dynamic analysis of region and partisanship. SAGE Open 7(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017697362