How to undertake a literature search: a step-by-step guide

Affiliation.

- 1 Literature Search Specialist, Library and Archive Service, Royal College of Nursing, London.

- PMID: 32279549

- DOI: 10.12968/bjon.2020.29.7.431

Undertaking a literature search can be a daunting prospect. Breaking the exercise down into smaller steps will make the process more manageable. This article suggests 10 steps that will help readers complete this task, from identifying key concepts to choosing databases for the search and saving the results and search strategy. It discusses each of the steps in a little more detail, with examples and suggestions on where to get help. This structured approach will help readers obtain a more focused set of results and, ultimately, save time and effort.

Keywords: Databases; Literature review; Literature search; Reference management software; Research questions; Search strategy.

- Databases, Bibliographic*

- Information Storage and Retrieval / methods*

- Nursing Research

- Review Literature as Topic*

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Literature Search: Databases and Gray Literature

The literature search.

- A systematic review search includes a search of databases, gray literature, personal communications, and a handsearch of high impact journals in the related field. See our list of recommended databases and gray literature sources on this page.

- a comprehensive literature search can not be dependent on a single database, nor on bibliographic databases only.

- inclusion of multiple databases helps avoid publication bias (georaphic bias or bias against publication of negative results).

- The Cochrane Collaboration recommends PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) at a minimum.

- NOTE: The Cochrane Collaboration and the IOM recommend that the literature search be conducted by librarians or persons with extensive literature search experience. Please contact the NIH Librarians for assistance with the literature search component of your systematic review.

Cochrane Library

A collection of six databases that contain different types of high-quality, independent evidence to inform healthcare decision-making. Search the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials here.

European database of biomedical and pharmacologic literature.

PubMed comprises more than 21 million citations for biomedical literature from MEDLINE, life science journals, and online books.

Largest abstract and citation database of peer-reviewed literature and quality web sources. Contains conference papers.

Web of Science

World's leading citation databases. Covers over 12,000 of the highest impact journals worldwide, including Open Access journals and over 150,000 conference proceedings. Coverage in the sciences, social sciences, arts, and humanities, with coverage to 1900.

Subject Specific Databases

APA PsycINFO

Over 4.5 million abstracts of peer-reviewed literature in the behavioral and social sciences. Includes conference papers, book chapters, psychological tests, scales and measurement tools.

CINAHL Plus

Comprehensive journal index to nursing and allied health literature, includes books, nursing dissertations, conference proceedings, practice standards and book chapters.

Latin American and Caribbean health sciences literature database

Gray Literature

- Gray Literature is the term for information that falls outside the mainstream of published journal and mongraph literature, not controlled by commercial publishers

- hard to find studies, reports, or dissertations

- conference abstracts or papers

- governmental or private sector research

- clinical trials - ongoing or unpublished

- experts and researchers in the field

- Library catalogs

- Professional association websites

- Google Scholar - Search scholarly literature across many disciplines and sources, including theses, books, abstracts and articles.

- Dissertation Abstracts - dissertation and theses database - NIH Library biomedical librarians can access and search for you.

- NTIS - central resource for government-funded scientific, technical, engineering, and business related information.

- AHRQ - agency for healthcare research and quality

- Open Grey - system for information on grey literature in Europe. Open access to 700,000 references to the grey literature.

- World Health Organization - providing leadership on global health matters, shaping the health research agenda, setting norms and standards, articulating evidence-based policy options, providing technical support to countries and monitoring and assessing health trends.

- New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature Report - a bimonthly publication of The New York Academy of Medicine (NYAM) alerting readers to new gray literature publications in health services research and selected public health topics. NOTE: Discontinued as of Jan 2017, but resources are still accessible.

- Gray Source Index

- OpenDOAR - directory of academic repositories

- International Clinical Trials Registery Platform - from the World Health Organization

- Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry

- Brazilian Clinical Trials Registry

- Chinese Clinical Trial Registry -

- ClinicalTrials.gov - U.S. and international federally and privately supported clinical trials registry and results database

- Clinical Trials Registry - India

- EU clinical Trials Register

- Japan Primary Registries Network

- Pan African Clinical Trials Registry

- TutorHome |

- IntranetHome |

- Contact the OU Contact the OU Contact the OU |

- Accessibility hub Accessibility hub

- StudentHome

- Help Centre

You are here

Help and support.

- Finding information on your research topic

- How do I do a literature search?

A literature search is a systematic, thorough search of a range of literature (for example books, peer-reviewed articles, etc.) on your topic. Commonly you will be asked to undertake literature searches as part of your Level 3 and postgraduate study.

Literature searching can be broken down into a series of iterative steps. You may want to revisit some of these several times throughout your search.

Planning your search

What to search for: keywords and phrases.

Start the process by clarifying the research question you would like answered. Your next step is to use your research question to help you identify keywords. The language and terminology of your module materials will help you to identify the most effective words for your search.

You can also identify keywords by looking for background information on key areas within your topic online as this will give you ideas for synonyms and other words commonly used.

The activity on Choosing good keywords will provide further guidance.

Where to search: Library Search, databases and Google Scholar

Now that you have your keywords you need to decide where to search. Library Search is a good starting point, particularly for unfamiliar topics, to provide background information and lead to further sources.

Each database has different content. It is therefore advisable to search several databases to make sure you do not miss a key paper on your topic. If you are unsure where to search, the Selected resources for your study page will help you find the most relevant databases.

You may also like to use Google Scholar too. The Access eresources using Google Scholar page shows how to add a "Find it at OU" button to Google Scholar search results.

Search techniques

Once you have your keywords you will need to combine them. You can use the help sheet on Advanced search techniques as guidance. You may also find the following activities useful:

The Library online training session on Smarter searching with library databases .

The activity on Filtering information quickly .

Further reading:

Byrne, D. (2017) Developing a researchable question . Project Planner . Sage Research Methods. DOI:10.4135/9781526408525.

Byrne, D. (2017) Reviewing the literature . Project Planner . Sage Research Methods. DOI:10.4135/9781526408518.

Evaluating information

It is important to evaluate the literature you find for quality and relevance. The PROMPT criteria will help with this. The longer Evaluating the quality of information activity provides more detail. (An OU login is required to access this activity.)

Organising information

When conducting a literature search recording the information you find in an organised manner is essential. Literature searches require you to read and keep track of many more articles than you would read for an assignment. You may want to try using a bibliographic management tool to help organise the references you have found. The Bibliographic management page introduces a selection of tools..

Keeping a record of the information you find could help you to save a lot of time. The Organising information activity introduces some methods to manage this material. (An OU login is required to access this activity.)

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Getting started with the online library

- Disabled user support

- Finding resources for your assignment

- Finding ejournals and articles

- Access eresources using Google Scholar

- Help with online resources

- Finding and using books and theses

- How do I do a citation search?

- Keep up to date

- Referencing and plagiarism

- Training and skills

- Study materials

- Using other libraries and SCONUL Access

- Borrowing at the Walton Hall Library

- OU Glossary

- Contacting the helpdesk

Smarter searching with library databases

Monday, 13 January, 2025 - 19:30

Learn how to access library databases, take advantage of the functionality they offer, and devise a proper search technique.

Library Helpdesk

Chat to a Librarian - Available 24/7

Other ways to contact the Library Helpdesk

The Open University

- Study with us

- Work with us

- Supported distance learning

- Funding your studies

- International students

- Global reputation

- Sustainability

- Apprenticeships

- Develop your workforce

- News & media

- Contact the OU

Undergraduate

- Arts and Humanities

- Art History

- Business and Management

- Combined Studies

- Computing and IT

- Counselling

- Creative Arts

- Creative Writing

- Criminology

- Early Years

- Electronic Engineering

- Engineering

- Environment

- Film and Media

- Health and Social Care

- Health and Wellbeing

- Health Sciences

- International Studies

- Mathematics

- Mental Health

- Nursing and Healthcare

- Religious Studies

- Social Sciences

- Social Work

- Software Engineering

- Sport and Fitness

Postgraduate

- Postgraduate study

- Research degrees

- Masters in Social Work (MA)

- Masters in Economics (MSc)

- Masters in Creative Writing (MA)

- Masters in Education (MA/MEd)

- Masters in Engineering (MSc)

- Masters in English Literature (MA)

- Masters in History (MA)

- Masters in International Relations (MA)

- Masters in Finance (MSc)

- Masters in Cyber Security (MSc)

- Masters in Psychology (MSc)

- A to Z of Masters degrees

- OU Accessibility statement

- Conditions of use

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Manage cookie preferences

- Modern slavery act (pdf 149kb)

Follow us on Social media

- Student Policies and Regulations

- Student Charter

- System Status

- Contact the OU Contact the OU

- Modern Slavery Act (pdf 149kb)

© . . .

Literature Searching

Introduction

Why do a literature search.

Literature searching is a critical component for any research project. It is the part of the project where you perform a thoroughly thought-out and well-organized search in the available research literature, usually conducted in a bibliographic database, to identify the depth and breadth of good quality articles and other publications on a specific topic. Literature searching is an iterative process, where you would repeat the process a number of times to ensure that you have found, to the best of your ability, as many relevant references on your topic as possible.

The reasons for conducting a literature search are numerous and include, but are not limited to:

- short fact-finding forays, to acquire background information on a topic,

- getting insight into the scope and breath of the literature on a particular topic,

- determining whether or not; or to what extent, research on a topic has already been done - --

- to the immensely comprehensive and lengthy evidence synthesis (https://evidencesynthesis.org/what-is-evidence-synthesis/), such as systematic reviews.

The ultimate goal of a literature search is to gain knowledge.

In addition, a literature search helps:

- to clarify or refine the research problem or question under consideration,

- checks to see if similar research has already been done on the topic,

- verifies that this is an important problem or question which needs answering or more research,

- highlights or fills in gaps of existing knowledge or research,

- helps to find measurement instruments, research methods or techniques,

- reveals/uncovers/discloses terminology related to the field/topic and,

- identifies researchers with similar interests.

References/Additional Resources

Brettle A., Gambling, T. (2003). Needle in a haystack? Effective literature searching for research . Radiography, 9(3), 229–236.

vom Brocke, J., Simons, A., Riemer, K., Niehaves, B., Plattfaut, R. and Cleven, A. (2015) Standing on the Shoulders of Giants: Challenges and Recommendations of Literature Search in Information Systems Research . Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 37, Article 9.

Grewal, A., Kataria, H., & Dhawan, I. (2016). Literature search for research planning and identification of research problem . Indian journal of anaesthesia, 60(9), 635–639.

Watson M. (2020). How to undertake a literature search: a step-by-step guide. British journal of nursing (Mark Allen Publishing), 29(7), 431–435.

- Next: Literature Searching vs. Literature Review >>

- Submission Guidelines

safety learning system header

Learning Objectives

(1) Explain steps in conducting a literature search

(2) Identify resources to utilize in a literature search

(3) Perform an online literature search using U of U Health resources

Valentina is a third year pediatric resident who notices that many of the teenagers she sees in clinic use their phones to play games and connect with friends and family members. She wonders if there could be an app for teenagers to manage their chronic diseases, specifically type 1 diabetes. But where does she begin?

What is a literature search?

iterature search is a comprehensive exploration of published literature with the purpose of finding scholarly articles on a specific topic . Managing and organizing selected scholarly works can also be useful.

Why do a literature search?

Literature search is a critical component for any evidence-based project. It helps you to understand the complexity of a clinical issue, gives you insight into the scope of a problem, and provides you with best treatment approaches and the best available evidence on the topic. Without this step, your evidence-based practice project cannot move forward.

Five steps for literature search success

There are several steps involved in conducting a literature search. You may discover more along the way, but these steps will provide a good foundation.

Plan using PICO(T) to develop your clinical question and formulate a search strategy.

Identify a database to search.

Conduct your search in one or more databases.

Select relevant articles .

Organize your results . Remember that searching the literature is a process.

#1: Plan using PICO(T)

The PICO(T) question framework is a formula for developing answerable, researchable questions. Using PICO(T) guides you in your search for evidence and may even help you be more efficient in the process ( Click here to learn all about PICO(T) ).

Once you have your PICO(T) question you can formulate a search strategy by identifying key words, synonyms and subject headings. These can help you determine which databases to use.

#2: Identify a database

For your search, you will need to consult a variety of resources to find information on your topic. While some of these resources will overlap, each also contains unique information that you won’t find in other databases.

The "Big 3" databases: Embase, PubMed, and Scopus are always important to search because they contain large numbers of citations and have a fairly broad scope. ( Click here to access these databases and others in the library's A to Z database.)

In addition to searching these expansive databases, try one that is more topic specific.

We are here to help.

If you are conducting a literature search and are not certain of the details, don't panic! U of U Health has a wealth of resources, including experienced librarians, to help you through the process. Learn more here.

Utah’s Epic-embedded librarian support

Did you know you can request evidence-based information from the library directly through Epic? Contact us through Epic’s Message Basket.

Eccles Health Sciences medical librarians are able to provide expertise in articulating the clinical question, identifying appropriate data sources, and locating the best evidence in the shortest amount of time. You can also send a message to ASK EHSL .

#3: Conduct your search

Now that you have identified pertinent databases, it is time to begin the search!

Use the key words that you’ve identified from your PICO(T) question to start searching. You might start your search broadly, with just a few key words, and then add more once you see the scope of the literature. If the initial search doesn't produce many results, you can play with removing some key words and adding more granular detail.

In our intro case study, Valentina’s population is teenagers with type 1 diabetes and her intervention is a mobile app. Watch the video below to see how Valentina uses the powerful Embase PICO search feature to identify synonyms for type 1 diabetes, mobile apps, and teenagers.

Example of Embase using PICO Why use Embase? This search casts a wider net than most databases for more results.

Common Search Terms and Symbols

AND Includes both keywords Narrows search OR Either keyword/concept Combine synonyms and similar concepts Expands search "Double quotes" Specific phrase Wildcard* Any word ending variants (singular, plural, etc.) Example: nurs* = nurse, nurses, nursing, etc.

Controlled Vocabulary

Want to help make your search more accurate? Try using the controlled vocabulary, or main words or phrases that describe the main themes in an article, within databases. Controlled vocabulary is a standardized hierarchical system. For example, PubMed uses Medical Subject Headings or MeSH terms to “map” keywords to the controlled vocabulary. Not all databases use a controlled vocabulary, but many do. Embase’s controlled vocabulary is called Emtree, and CINAHL’s controlled vocabulary is called CINAHL Headings. Consider focusing the controlled vocabulary as the major topic when using MeSH, Emtree, or CINAHL Headings.

For Valentina’s question, there are MeSH terms for Adolescent, Diabetes Mellitus, Type 1, and Mobile Applications.

Example of PubMed using MeSH MeSH helps focus your PubMed search

Talk with your librarians for more help with searching with controlled vocabularies.

Every database uses filters to help you narrow your search. There are different filters in each database, but they tend to work in similar ways. Use filters to help you refine your search, rather than adding those keywords to the search. Filters include article/publication type, age, language, publication years, and species.

Using filters can help return the most accurate results for your search.

Article/publication types, such as randomized controlled trial, systematic reviews, can be used as filters.

Use an Age Filter, rather than adding “pediatric” or “geriatric” to your search.

Valentina uses the age filter for her question rather than as a keyword in the video below.

Example of a PubMed keyword search using filters PubMed is the most common search because it is the most widely available.

#4: Select relevant articles

Once you have completed your search, you’ll select articles that are relevant to your question. Some databases also include a “similar articles” feature which recommends other articles similar to the article you’re reviewing—this can also be a helpful tool.

When you’ve identified an article that appears relevant to your topic, use the “Snowballing” technique to find additional articles. Snowballing involves reviewing the reference lists of articles from your search.

In other words, look at your key articles and review their reference list for additional key or seminal articles to aid in your search.

#5: Organize your results

As you begin to collect articles during your literature search, it is important to store them in an organized fashion. Most research databases include personalized accounts for storing selected references and search strategies.

Reference managers are a great way to not only keep articles organized, but they also generate in-text citations and bibliographies when writing manuscripts, and provide a platform for sharing references with others working on your project.

A number of reference managers—such as Zotero , EndNote , RefWorks, Mendeley , and Papers are available. EndNote Basic (web-based) is freely available to U of U faculty, staff and students. If you need help with this process, contact a librarian to help you select the reference manager that will best suit your needs.

Using these steps, you’re ready to start your literature search. It is important to remember that there is not a right or wrong way to do the search. Literature searches are an iterative process—it will take some time and negotiation to find what you are looking for. You can always change your approach, or the information resource you are using. The important thing is to just keep trying. And before you get frustrated or give up, contact a librarian . They are here to help!

This article originally appeared May 12, 2020. It was updated to reflect current practice on March 14, 2021.

Tallie Casucci

Barbara wilson.

You have a good idea about what you want to study, compare, understand or change. But where do you go from there? First, you need to be clear about exactly what it is you want to find out. In other words, what question are you attempting to answer? Librarian Tallie Casucci and nursing leaders Gigi Austria and Barb Wilson help us understand how to formulate searchable, answerable questions using the PICO(T) framework.

EBP, or evidence-based practice, is a term we encounter frequently in today’s health care environment. But what does it really mean for the health care provider? College of Nursing interim dean Barbara Wilson and Nurse manager Gigi Austria explain how to integrate EBP into all aspects of patient care.

Frequent and deliberate practice is critical to attaining procedural competency. Cheryl Yang, pediatric emergency medicine fellow, shares a framework for providing trainees with opportunities to learn, practice, and maintain procedural skills, while ensuring high standards for patient safety.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Receive the latest insights in health care impact, improvement, leadership, resilience, and more..

Contact the Accelerate Team

50 North Medical Drive | Salt Lake City, Utah 84132 | 801-587-2157

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Learning to successfully search the scientific and medical literature

Emily a thompson, laurissa b gann, erik n k cressman.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2019 Feb 11; Revised 2019 Feb 16; Accepted 2019 Feb 19; Issue date 2019 Mar.

Searching the literature is often overlooked and receives inadequate attention. In this article, we seek to address this issue by presenting several strategies. Here, five steps are outlined and discussed to facilitate effective literature searching.

Keywords: Literature, Search, Database, Publication, Autoalert, Citation mining, Search strategy

Rapidly and thoroughly understanding published literature in a new area of research is a challenge for graduate students in the life sciences, medical students, and veterinary students, but the issue applies in any area of science. Using powerful tools with a focused strategy is of tremendous assistance in learning the literature on a topic in a timely manner. Acquiring this skill set is essential, but it is often overlooked, causing frustration, wasted time, and wasted resources, and can result in unnecessary duplication of effort. Frank Westheimer, noted chemist and National Science Medal Awardee, is credited with the statement, “A couple of months in the laboratory can frequently save a couple of hours in the library” (Crampon 1988 ). Some would argue that a couple of months is a significant underestimate of the time involved. This article will detail a functional and systematic approach to a literature search using tools that were unavailable in Westheimer’s day and describe how to leverage the power of online resources.

What type of question is being asked?

When beginning a literature search, it is important to consider the type of information in question because the nature of the question will dictate the search approach. For example, questions concerning a drug, disease, or general medical information can be answered by reviewing sources such as UpToDate ( www.uptodate.com ) or DynaMed ( www.dynamed.com/home/ ). For clinical questions or questions regarding clinical research, PubMed Clinical Queries is a readily available resource. Further, for more encompassing literature searches, such as those beginning a new research project, a database such as PubMed or Web of Science is necessary for a comprehensive search of scientific literature. Other fields will have similar comprehensive databases but are outside the scope of this article.

Five steps are necessary to perform a comprehensive search: develop a focused question, plan the search, execute the plan, track and store results, and finally, stay current with newly published material.

Ask a focused question

Form a question.

A sound strategy is to begin with a question that is focused, well-defined, and answerable. Diving into a literature review without clearly identifying the question will lead to lost time, and frustration. The PICO tool (as seen in Table 1 ) was designed to help researchers think through their proposed topic by breaking it down into concepts (Richardson et al. 1995 ). Overlooking this step can lead to a search that is much too broad or too narrow. A question that is too broad may lead to too many search results, and a question that is too narrow will lead to the opposite. The PICO tool also assists in generating keywords or search terms that will assist authors later in their database searching.

PICO tool acronym and description

Explore the question

After defining a question, perform an exploratory search to determine if the question is original or not. Very often, a seemingly original idea has already been explored by others and the novice researcher is only just entering the fray. At this point, it should be confirmed that the question under review is both answerable and has not already been answered by other authors. To gain a better understanding of the topic, and to ensure a completed PICO model, search DynaMed, UpToDate, Google, books, or PubMed Clinical Queries for preliminary information.

Finalize the question

As experienced researchers can often provide advice concerning question formulation, it is advisable to review the topic and proposed question with potential collaborators/co-authors. Discussing with collaborators and co-authors also ensures that all parties are in agreement with the potential research project and scope of the literature search.

Plan the literature search

Before searching, determine what search methods are available and strategize how to best use them.

Determine appropriate databases

Make a list of databases that can be used to search for information related to the topic. While there may be content overlap between databases, each will contain unique material as well. Thus, multiple databases should be investigated for a comprehensive review. Investing time in learning how to navigate these databases is worthwhile. Each database has unique searching features which will help focus a search. If unsure, contact an experienced collaborator, co-author, or medical librarian who can provide advice. Table 2 identifies databases that are often recommended in the medical sciences.

Databases common in medical sciences

Develop the search strategy

After selecting appropriate databases, develop a comprehensive search strategy for database searching. A comprehensive strategy should include a combination of keywords and subject headings or index terms.

Find a pivotal/seminal paper

Often, the best starting point is to find one seminal or pivotal paper to serve as a guide for the entire search. A pivotal paper is one that is highly cited and provides crucial information the field builds upon. In some cases, it may be a review article rather than a major scientific study. In other words, a pivotal paper is one that serves as a building block for the field. For a researcher, this paper can stand as the basis of the literature search. Start by performing a quick preliminary search in Web of Science, Google Scholar, or Scopus. The key feature of these databases is that they all have a sorting function that enables display of the results by the number of times a paper has been cited. Some databases may also suggest related citations. This will provide another starting point from which the literature search can continue. (1) Repeating the algorithm of who cited a paper, (2) sorting the resulting list by number of citations, and (3) selecting the most cited paper(s) and determining who cited them are powerful, leveraged approaches that will quickly produce a fairly comprehensive set of important papers and prominent investigators within a particular field.

Choose keywords

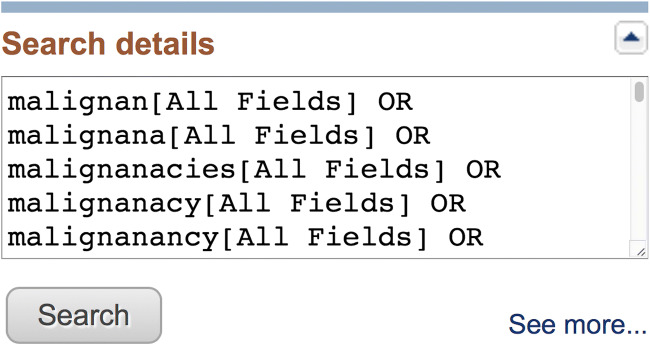

Keywords should be used alongside subject headings to capture any alternate concepts that cannot be captured with subject headings alone. It may take several months for subject headings to be applied to an article after it appears in a database, and some concepts are not easily defined with one term. For example, hematologic malignancies require multiple subject headings or keywords to search for all possible hematologic cancers (i.e. leukemia, lymphoma). When selecting keywords, remember to include synonyms (ultrasonography vs. ultrasound, elasticity imaging[MeSH] vs elastography), differences in spelling, suffixes, and generic and trade names of drugs, and be sure to spell out abbreviated words (i.e., FISH or fluorescence in situ hybridization). Learn to truncate with wild card symbols according to the syntax of any given software. An example of truncation is the asterisk used in PubMed to permit a search using any possible permutations of a root term. For instance, if you search PubMed for malignan*, PubMed will retrieve malignant, malignancy, malignancies, etc. After searching, one can review the search details box on the right-hand side of the search results page as shown in Fig. 1 to find out which permutations PubMed applied to the truncated term. Note in this example, the scroll bar indicates that there are many additional permutations not shown, and be aware that truncation may not be appropriate for every search as it can broaden your search significantly.

Example of PubMed expansion of the truncated search term “malignan*” using the wild card asterisk. This is section is found on the right side of the search result page. Note the scroll bar to the right indicating many additional variations not shown in the window and the link to see more terms used

Identify subject headings

Subject headings are a set of descriptive vocabulary terms organized in a hierarchical structure within a database. Headings are important because they identify the most important concepts in the article. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) is a tool provided by PubMed and Medline that enables readers to explore the database of terms or “mine search results” by looking at the MeSH terms associated with similar articles (see citation mining below). These can be found under the article abstract in a collapsible menu titled MeSH. Be sure to note that it may take a few months before MeSH terms are added for an article, so they may not be available for recently published items. In particular, pay close attention to MeSH terms from any pivotal papers you identify along the way. These MeSH subheadings may not have been terms that you initially used, or they may help you be more specific, and are frequently a fast yet effective way to narrow down your search to results that are truly meaningful.

Use Boolean language

Many databases and search engines capitalize on the use of Boolean language. Commonly, the use of AND, OR, or NOT can be used to combine, link, or exclude search terms. Try this when looking to expand or narrow a search.

Define inclusion and exclusion criteria

From the beginning, determine characteristics of which articles should be included in the literature search. Critically consider date ranges, languages, type of manuscript, and type of study. It can be tempting to only include recent articles (last 10 years) or articles in a certain language, but keep in mind that a pivotal or foundational article could be excluded if outside the bounds of the search criteria. Searching the older literature can help one understand the history and scientific progression of a field. Often, seemingly new ideas will have already been explored decades earlier.

Confirm with collaborators

Converse with co-authors and discuss search strategy and inclusion criteria.

Perform the search

Translate the search to databases.

Each database has a unique structure so be prepared to modify search terms to match the searching features of each database. Follow the search strategy outlined above as closely as possible and be aware that variations will exist between databases.

Track search methods

Keep track of search methods used throughout the literature search. This is an important part of research reproducibility and will be useful when writing a literature review. Note the databases searched, inclusion and/or exclusion criteria, and the search terms used. Consider also recording inclusion and/or exclusion criteria agreed upon after discussion with co-authors. Often, a spreadsheet or similar document is helpful to organize this information. Since a search is often a dynamic process with many branches, tracking helps to avoid unnecessary duplication.

Search beyond databases

Not every important reference is in a database. Alternatively, an important reference may reside in a database already searched, but was not identified with a particular search strategy because of how the reference was indexed. Depending on the topic, it may be useful to try citation mining, cited reference searching, or looking at the gray literature.

Citation mining

Citation mining is a search strategy that entails using a previously found pivotal citation to discover further relevant citations. This method involves determining who has cited an article since it was first published and exploring those people or research groups. This is a powerful way to find related articles, search more recently published literature, and analyze the impact of the original publication. Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar offer this functionality. Repeating this process as described above can quickly provide a broad overview of important contributions and contributors.

Gray literature

Gray literature refers to materials that are not published in journals or searchable in a database. This includes guidelines, clinical trials, open data, reports, conference proceedings, and other government or organizational documents. Gray literature resources will vary based on the topic.

Saving, storing, and sharing

Literature searches can be time consuming and may take days, weeks, or even months to complete. It is important to stay organized by saving searches and search results along the way.

Saving the search

Most databases include a feature that allows searches to be saved. For example, creating a free NCBI account in PubMed is available to the public and enables users to save previous searches. It is a good idea to save various iterations of the chosen search strategy so results can be easily reproduced. To save a search, log in to an NCBI account, search PubMed, choose Create Alert underneath the search box, and customize the search. Here, options include simply saving the search or email updates.

Save references

Reference manager software is a powerful tool for organizing, storing, and sharing references. It will also save time when creating a bibliography. A number of tools are available for authors, some of which are available at no cost. Check with a librarian to see what resources are available at your institution.

Mendeley (desktop, online) and Zotero (online only)—note that there are typically limited amounts of storage in the free versions.

Commercially available tools

EndNote (desktop, online) and RefWorks (online only)—check with your librarian as one or more may already be available via your institution.

Staying current

Stay current.

Databases are constantly changing, with new material being added daily. It is imperative to maintain familiarity with the published literature even after completing a literature search. It may take months or even years to complete a manuscript, and relevant articles will likely be published in the meantime. Many authors will save their search strategies in different databases and re-run the search immediately before submission to make sure they have not missed recent publications (see Save the Search Strategies above). Keeping up with literature on a daily or weekly basis may include setting aside some time each day or each week to read through alerts and/or relevant articles on social media. It is not necessary to redo the entire literature search, but it is important to keep up with recent publications. Save articles and citations using tools like BrowZine, Refworks, Mendeley, and EndNote. Here are a few ways to keep up-to-date:

Email alerts

Databases like PubMed and Scopus allow users to create customized alerts by saving a search strategy. The strategy may combine multiple terms or perhaps simply track the output of an author (a major contributor to the field for example). One can then customize the frequency and volume of alerts to receive a weekly or monthly email regarding new publications. Similarly, Google has a function to set up news alerts about the latest press releases from major companies and organizations.

Follow major journals

Most major journals offer a feature for setting up email alerts through their website. However, setting up alerts for each individual journal can quickly overwhelm any email inbox. Try using tools like Read by QxMD or BrowZine to curate a list of journals to follow. However, be aware of confirmation bias. Following only specific journals will limit the breadth of literature exposure.

Social media

Social media is a powerful tool for collaboration, education, and learning. Twitter, Facebook, Research Gate, and other social media platforms are being used by many researchers, doctors, and academics to keep up with the latest news and research. If choosing to use these platforms, be sure to follow a variety of news, professional journals, and organization resources to avoid creating a platform for confirmation bias. Keep in mind that benefit can be gained from reading about opposing views and controversial subjects. Additionally, be sure to weigh the risks and balances of using social media before diving in. It is always good to question validity, but this becomes especially important when searching non peer-reviewed material.

Overall, the literature search is a daunting task that is best tackled systematically. Following the five steps outlined in this article will provide an effective approach to starting and completing a literature search.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Emily A. Thompson, Email: [email protected]

Laurissa B. Gann, Email: [email protected]

Erik N. K. Cressman, Email: [email protected]

- Crampon JE. Murphy, Parkinson, and Peter - laws for libraries. Libr J. 1988;113:37–41. [ Google Scholar ]

- Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;123:A12–A13. doi: 10.7326/ACPJC-1995-123-3-A12. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (266.6 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Scientific and Scholarly Writing

How to do a literature search, plan your search, execute/evaluate/revise, predefined searches and search hedges, literature searching resources.

- PubMed and other NLM Literature Databases

- Tracking and Citing References

- Parts of the paper

- Writing Effectively

- Where to Publish?

- Avoid Plagiarism

Thinking of performing a systematic review or another type of review

- Check out our Systematic Review Guide!

A literature search is a systematic survey of the research that's been published on your topic. You'll need to:

- Plan (define what you're looking for and decide where to look);

- Execute your search;

- Evaluate what you find; and

- Revise your search until you're confident that you've found everything that's applicable to your topic.

Ask a librarian if you get stuck at any point in your literature search.

What are you looking for?

At this point, you should have your research question and some familiarity with your topic. Write out your research question, isolate your key terms and write out as many synonyms as you can think of for each term. Doing this helps ensure that you are surveying the literature, not just finding relevant articles.

Where are you looking?

You should search in several databases. Again, this helps ensure that you are surveying the literature, not just finding relevant articles. PubMed is a good place to start for most searches. Consider the databases below, as well.

Ovid, like PubMed, searches MedLine. Coverage is similar, but not identical, which makes it a reliable way to double check your PubMed search found everything.

Avoid looking through duplicates by using the advanced search option to exclude PubMed results.

Scopus covers a much wider range of subjects than PubMed. It includes life sciences, health sciences, physical sciences, social sciences, and the arts and humanities.

Use Scopus if your topic is interdisciplinary.

- Scopus Overview presentation Overview of the Scopus database covering: how to create a basic search in Scopus for a topic, author, or an organization; use Boolean operators, filters, and phrase searching to search and find full text articles in Scopus; and save searches, set up search alerts, save lists of citations, and export citations.

- A-Z Database List Full list of databases from the Lamar Soutter Libary

Having trouble finding relevant resources? Finding the same articles over and over?

- Try different synonyms for your key terms . Spell out acronyms. Check MeSH or a medical thesaurus. See if the papers you've found have any keywords that can help you describe what you're looking for.

- Divide your search into parts. Instead of looking for a perfect paper that addresses your whole project, look for several that address different aspects of your paper.

- Remembering your search history for six months

- Able to save searches and set up searches alerts so you always know when something new has been published on your subject

- Able to save articles to collections

- Help you keep track of your own publications and make grant reporting easier as your career progresses

- You can also add the UMass Chan Outside Tool to your account so you will see the Check for UMass Chan full text button whenever you are logged in. Watch the video tutorial on how to add the UMass Chan Outside Tool .

- Similarly, you can create accounts in other databases to save searches, set alerts, and/or create collections of articles.

- Follow a good citation. Scopus has a citation mapper, that lets you see the articles that a particular paper cites, as well as the articles that have cited that particular paper. PubMed shows related citations and articles that have cited a particular paper on the right hand column.

- PubMed Clinical Queries PubMed/MEDLINE search feature that filters results in order to display only articles backed by good evidence. NOTE: At the PubMed home page, choose the Clinical Queries option from the choices under "PubMed Tools."

- Health Services Research (HSR) PubMed Queries Specialized PubMed searches on healthcare quality and costs.

- Health Sciences Search Hedges from the University of Alberta

- ISSG Search Filters Resource Produced by the InterTASC Information Specialists' Sub-Group. Aims to provide easy access to published and unpublished search filters.

- CADTH Search Filters Database From the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health.

- OVID Expert Searches Search hedges created by Ovid to find articles by study design, health condition, and population in various databases (Embase, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO).

- searchRxiv Open repository that researchers can use to store and share their searches performed for evidence synthesis and systematic reviews in various databases (CINAHL, Embase, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Scopus).

- Planning a Search Strategy Excellent overview from University of Edinburgh library.

- Identifying the Evidence for Public Health Reviews From the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

- Searching for Research Evidence in Public Health Training modules from the National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools, Canada.

- Glossary of Population Health Study Designs From the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

- << Previous: Home

- Next: PubMed and other NLM Literature Databases >>

- Last Updated: Nov 18, 2024 10:21 AM

- URL: https://libraryguides.umassmed.edu/scientific-writing

A free, AI-powered research tool for scientific literature

- Meredith Clausen

- Nanotechnology

- Ideal Gas Law

New & Improved API for Developers

Introducing semantic reader in beta.

Stay Connected With Semantic Scholar Sign Up What Is Semantic Scholar? Semantic Scholar is a free, AI-powered research tool for scientific literature, based at Ai2.

- Chester Fritz Library

- SMHS Library Resources

- Thormodsgard Law Library

Best Practices for Communicating Your Research

- Step 1: Your Manuscript

- Step 2: Authorship

- Step 3: Research Transparency

Search Strategies

Types of literature, search techniques, documenting & organizing, references & further reading.

- Library Books

- Dissertations & Theses This link opens in a new window

- Topics in Scholarly Communication This link opens in a new window

- Literature Reviews This link opens in a new window

On This Page:

Your search strategy, search strategy resources.

- Documenting & Organizing Your Search

Your search strategy for identifying appropriate research and literature for your literature review will change depending on your topic, the type of research you are conducting, the manuscript you plan to write, and the particular resource/database you are searching. It will also depend on how much time you have to conduct the search--is this a short- or long-term project or research paper? Does it require an initial scoping review? Read more about review types in Step 1 . You will need to identify appropriate (both discipline-specific and general) research databases, and a variety of search terms and limiters (e.g., population, geographic region, date) according to your research type, topic, and manuscript type.

Though the literature search is listed as Step 4 in this guide, often, you will have begun a brief, investigative literature search or scoping review before engaging in transparent research and pre-registering your research ( Step 3 ) as you need to be able to have some idea of how much literature there is out there on your topic before you solidify your hypothesis or systematic review question. This knowledge of pre-existing literature is of the utmost important when completing a thesis or dissertation. If you are conducting a short-term project with a looming deadline that does not need to be comprehensive as far as finding and synthesizing all topical existing/previous research, you can conduct a more economical but relevant search of the literature by targeting 2-4 specific databases and using carefully selected search terms.

Defining Your Research Question

It is integral to spend time honing and defining your research question before searching the literature. Highly recommended by faculty and librarians alike, are these two tools to help you define your research question:

- PICOT / PICO (quantitative evidence-based research/synthesis) and

- SPIDER (qualitative evidence-based research/synthesis)

PICO (Quantitative) and SPIDER (Qualitative)

Cooke, Smith, & Booth (2012).

*The "T" (PICOT) is left out of the above study. It represents Time, or the duration of data collection (Riva, Malik, Burnie, Endicott, & Busse, 2012)

Engineering PICO*

P = Population, Problem, Process

I = Intervention, Inquiry, Investigation, Improvement

C = Comparison (current practice or opposing viewpoints)

O = Outcomes (measuring what worked best)

*Read more about it on Arizona State University Library's "Engineering -- Formulating questions w/PICO" guide: https://libguides.asu.edu/engineering/PICO

Some of the best sources for learning how to conduct a systematic review of the literature, or a review for the introduction of a research report, are in books. Check out the Library Books page for some examples. Relevant research articles are also included on this page. Your Subject Librarian is here to help - set up a research consultation with us today!

Strategies for searching the literature for your literature review change depending upon the type of research you are conducting: primary research or research synthesis. Whether you are collecting new data (primary research), or synthesizing results of previous studies (review articles, including systematic reviews and meta-analyses), the first, and most important step before searching the literature, is to: define the target population (or thing) you are investigating in the case of primary research , or all studies that test a particular hypothesis or address a particular problem in the case of research synthesis (Cooper, 2010).

Where Will You Look?

The literature you gather greatly depends upon the sources that you look in. Studies appearing in peer-reviewed journals are easy to locate but will likely over-represent significant and novel results, while certain types of grey literature (e.g., dissertations and theses; self-published manuscripts; unpublished studies; conference abstracts, presentations, and proceedings; regulatory data; unpublished trial data; government publications; reports such as white papers, working papers, and internal documentation; patents; and policies & procedures) may be more difficult to find and access in full text--for example, you may need to contact authors or organizations directly. It is good practice to use listserv and distribution lists for this type of material along with direct personal contacts, keeping in mind that the latter may bias the results towards those in support of a particular contact's central beliefs and research results (Cooper, 2010).

Obviously, this means that limiting your search to journals in databases may skew results towards statistically significant findings, biasing your pool of studies which would be lacking in null, or inconclusive, results. You can also search for grey literature in institutional repositories like UND Scholarly Commons , government/professional organizations and conference websites, Open Data Repositories , open preprint repositories, theses and dissertation databases, online Researcher Communities , and journals that publish Registered Reports or null and inconclusive findings like PLOS ONE .

Author's Versions & Grey Literature Database Examples:

Dissertations from 1861 - present. Master's theses from 1988 - present. Includes full text from both UND and external dissertations and theses. Hosted by Proquest.

A secure cloud-based repository where you can search and find data sets and store your own data, ensuring it is easy to share, access and cite, wherever you are.

- Open Science Framework Search Search OSF projects and data files. OSF is a free and open source project management repository that supports researchers across their entire project lifecycle.

- UND Scholarly Commons The institutional repository is a service of the University of North Dakota libraries. Research and scholarly output included here has been selected and deposited by the individual university departments and centers on campus.

How Will You Look?

Conventional subject searching in databases.

A full, systematic search involves the development of a search strategy around subject terms, reflecting aspects of the research question. Searches are typically carried out in several or more multidisciplinary or discipline-specific databases. Searches are often restricted by language and date, and sometimes geographic region, through the use of database limiters . Your subject search will likely identify the majority of references ultimately included in your review, however, additional search methods, as described below, are necessary to locate additional unique and appropriate sources for your review.

Citation Chaining & Citation Searching (Backward & Forward Snowballing)

These techniques refer to checking reference lists and citing articles (articles that have cited the article that you are currently looking at). Citation chaining involves checking references on all included papers identified by various search methods so that relevant references not yet identified can be added to the pool of included studies. It also includes checking articles that cited an included paper. Many research databases link citing articles to each article record. Databases that are useful for citation searching include Google Scholar, Scopus, CINAHL Complete, Wiley Online, and others. Access Chester Fritz Library's most used databases by visiting our home page and clicking on QuickLinks or the complete list by visiting our A-Z Databases page .

Traditional vs. Comprehensive Pearl Growing

Traditional Pearl Growing (TPG) begins with one or more target articles, judged to be such due to their relevancy to the research topic. The target article is called a pearl. It's a step beyond the citation chaining and searching methods. The researcher then identifies keywords to add to their search from aspects of the article (e.g., abstract, subject terms, author, etc.). Hawkins and Wagers (1982) coined this process as "growing more pearls" (as cited in Schlosser, Wendt , Bhavnani , & Nail‐Chiwetalu, 2006).

Comprehensive Pearl Growing (CPG) involves the following process: (1) Start with a compilation of studies from a relevant review or a topical bibliography; (2) determine relevant databases for these studies; (3) determine how these studies are indexed in database 1 in terms of keywords and quality filters; (4) find other relevant articles in database 1 (or as many are relevant) using the index terms in a Building Block query; and (5) end when articles retrieved provide diminishing relevance. Thus, rather than beginning with only one pearl, CPG requires of the searcher to begin with a compilation of studies from a relevant narrative review or a topical bibliography. Like TPG, CPG makes use of existing studies to determine the keywords and quality filters under which they are indexed in order to retrieve more articles of the same kind (Schlosser, Wendt, Bhavnani, & Nail‐Chiwetalu, 2006).

Although pearl growing techniques are effective across disciplines, they may be particularly strategic for interdisciplinary research questions in which multiple controlled vocabularies (e.g., thesauri, database subject terms, discipline-specific terminology), are integral to pulling together sources across research databases (Schlosser, Wendt, Bhavnani , & Nail‐Chiwetalu, 2006).

Text-Mining

In Software Engineering, various text-mining (TM) techniques are used more and more to implement systematic literature review processes, however further research is needed--read Feng, Chiam, and Lo (2017) linked below for more information.

Check out our Library Books on reviews and research synthesis to take your literature search to the next level by creating coding criteria for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Document Your Literature Search

Use paper and pen, the below excel file, or online tools or applications like Trello to set up a system for documenting your search strategy. This contributes to research transparency and gives you a mechanism to provide quick and accurate documentation of your search strategies when pre-registering systematic review protocol or being questioned about how you searched the literature (and what you may have missed) by supervisors, colleagues, or reviewers.

- Search Strategy Documentation Template Be systematic by documenting your search strategy (keywords, databases, etc.). This helps you to remember what you have done before and provides documentation for research transparency.

For systematic reviews or meta-analyses, use the PRISMA or MOOSE checklists to evaluate each included resource for inclusion.

- PRISMA Checklist Transparent Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses.

- MOOSE Guidelines for Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews of Observational Studies* *Modified from Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12.

Organize Your Literature

- Citation Managers A research guide providing information and resources for a handful of the most popular citation managers.

- EndNote @ UND Page of the Citation Managers research guide discussing UND's EndNote subscription and use.

- EndNote Citation management software subscribed to UND and free for UND staff, faculty, and students.

- Mendeley Mendeley (Elsevier) is a free reference manager and an academic social network. Manage your research, showcase your work, connect and collaborate.

- Zotero Zotero is a free, easy-to-use citation management tool to help you collect, organize, cite, and share research.

- Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis Cooke, A., Smith, D., & Booth, A. (2012). Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1435-1443.

- Checking reference lists to find additional studies for systematic reviews Horsley, T., Dingwall, O., & Sampson, M. (2011). The Cochrane Library, 8.

- Domain Definition and Search Techniques in Meta-analyses of L2 Research (Or why 18 meta-analyses of feedback have different results) Plonsky, L., & Brown, D. (2015). Second Language Research, 31(2), 267–278.

- Effectiveness and Efficiency of Search Methods in Systematic Reviews of Complex Evidence: Audit of Primary Sources Greenhalgh, T., & Peacock, R. (2005). BMJ, 331(7524), 1064-1065. Only 30% of sources were obtained from the protocol defined at the outset of the study (that is, from the database and hand searches). Fifty one per cent were identified by “snowballing” (such as pursuing references of references), and 24% by personal knowledge or personal contacts. Conclusion: Systematic reviews of complex evidence cannot rely solely on protocol-driven search strategies.

- An Empirical Assessment of A Systematic Search Process for Systematic Reviews Zhang, H., Babar, M. A., Bai, X., Li, J., & Huang, L. (2011, April). In Evaluation & Assessment in Software Engineering (EASE 2011), 15th Annual Conference on (pp. 56-65). IET.

- The Impact of Limited Search Procedures for Systematic Literature Reviews – A Participant-Observer Case Study Kitchenham, B., Brereton, P., Turner, M., Niazi, M., Linkman, S., Pretorius, R., & Budgen, D. (2009, October). In Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement, 2009. ESEM 2009. 3rd International Symposium on (pp. 336-345). IEEE.

- Information retrieval in systematic reviews: Challenges in the public health arena Beahler, C. C., Sundheim, J. J., & Trapp, N. I. (2000). American Journal of Preventive Medicine, (18)4, 6-10.

- Literature Searching for Social Science Systematic Reviews: Consideration of a range of search techniques. Papaioannou, D. , Sutton, A. , Carroll, C. , Booth, A. and Wong, R. (2010). Health Information & Libraries Journal, 27, 114-122.

- Literature search strategies for conducting knowledge‐building and theory‐generating qualitative systematic reviews Finfgeld‐Connett, D., & Johnson, E. D. (2013). Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(1), 194-204.

- Performing a Literature Review. Reed, L. E. (1998, November). In fie (pp. 380-383). IEEE.

- Searching for qualitative research for inclusion in Systematic Reviews: A Structured Methodological Review Booth, A. (2016). Systematic Reviews, (5)74, 1-23.

- Should We Exclude Inadequately Reported Studies From Qualitative Systematic Reviews? An Evaluation of Sensitivity Analyses in Two Case Study Reviews Carroll, C., Booth, A., & Lloyd-Jones, M. (2012). Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1425-1434.

- Systematic Literature Studies: Database Searches vs. Backward Snowballing Jalali, S., & Wohlin, C. (2012, September). In Proceedings of the ACM-IEEE international symposium on Empirical software engineering and measurement (pp. 29-38). ACM.

- Text-Mining Techniques and Tools for Systematic Literature Reviews: A Systematic Literature Review Feng, L., Chiam, Y. K., & Lo, S. K. (2017, December). In Asia-Pacific Software Engineering Conference (APSEC), 2017 24th (pp. 41-50). IEEE. Also available open access: http://eprints.um.edu.my/18515/1/All.pdf

- Use of information-seeking strategies for developing systematic reviews and engaging in evidence-based practice: the application of traditional and comprehensive Pearl Growing. A review Schlosser, R. W., Wendt, O., Bhavnani, S., & Nail‐Chiwetalu, B. (2006). International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 41(5), 567-582.

- What is your research question? An introduction to the PICOT format for clinicians. Riva, J. J., Malik, K. M., Burnie, S. J., Endicott, A. R., & Busse, J. W. (2012). The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 56(3), 167-71.

- << Previous: Step 3: Research Transparency

- Next: References & Resources >>

- Last Updated: Nov 4, 2024 4:42 PM

- URL: https://libguides.und.edu/communicating-research

Literature Searching

In this guide.

- Introduction

- Steps for searching the literature in PubMed

- Step 1 - Formulate a search question

- Step 2- Identify primary concepts and gather synonyms

- Step 3 - Locate subject headings (MeSH)

- Step 4 - Combine concepts using Boolean operators

- Step 5 - Refine search terms and search in PubMed

- Step 6 - Apply limits

Formulating a Well-Defined, Answerable Research Question

It is important to develop a well-defined, answerable research question because it

- Defines the focus of your literature search

- Identifies the appropriate study design and methods

- Makes searching for evidence simpler and more effective

- Helps you identify relevant results and separate relevant results from irrelevant ones

Tips for developing a clinical research question:

- The question is directly relevant to the most important health issue for the patient

- The question is focused and when answered, will help the patient the most

- The question is phrased to facilitate a targeted literature search for precise answers

Adopted from CEBM: what makes a good clinical question

Example of a vague question:

"Is mobile technology good at managing diabetes?"

- Mobile technology is very broad. Mobile apps, mobile phones, voice/text?

- What does “good” mean? How will you determine if the technology is effective?

- What kind of diabetes? Type 1? Type 2? Both?

- Who are the “patients”? Adults? Adolescents? Women? Patients with specific diagnoses?

- Any time frame?

Example of a well-defined question:

"Are mobile health technology interventions more effective in managing patients with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes than in-person care?"

PICO Framework

PICO or PICO(T) (patient/problem/population, intervention, comparison, outcome, time) is a well-known approach for framing a research question. It divides the research question into key components making it easy and searchable.

Example: "Are mobile health technology interventions more effective in managing patients with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes than in-person care?"

Other question formulation frameworks:

PIE (Population, Intervention, Effect / Outcome)

SPIDER (Sample, Phenomena of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type)

SPICE (Setting, Perspective, Intervention, Comparison, Evaluation)

ECLIPSE (Expectation, Client group, Location, Impact, Professionals, Service)

- << Previous: Steps for searching the literature in PubMed

- Next: Step 2- Identify primary concepts and gather synonyms >>

- Last Updated: Jul 10, 2024 2:17 PM

- URL: https://laneguides.stanford.edu/LitSearch

- Search resources

- Resource guides

Grey literature

What is grey literature.

Grey literature is any information that is not produced by commercial publishers.

This resource guide describes the different types of grey literature, suggests a number of search tools and resources you can use to find this sort of information and gives some tips on how to search effectively for this hard-to-find material.

Grey literature includes these types of publication:

- research reports

- working papers

- conference proceedings

- white papers

- social media posts

- policy documents

- reports produced by government departments, academics, business and industry.

Grey literature can help you to:

- find current information on emerging areas of research – before research is formally published in a journal or book, authors might share information about new and emerging research in blogs, social media, preprints, conference proceedings or in their thesis

- hear from a more diverse range of voices – not everyone has the opportunity to publish with mainstream commercial publishers

- identify research that has null or negative results – negative results are less likely to be published in journals

- find information published by government agencies, policy organisations, think tanks, non-governmental organisations, industry, trade or regulatory or professional bodies.

However, grey literature is not peer reviewed, so the quality of information may be variable. You need to use your judgement and critical thinking skills to assess the information, ideas and arguments you find.

IMAGES

VIDEO