- Login / Sign Up

Believe that journalism can make a difference

If you believe in the work we do at Vox, please support us by becoming a member. Our mission has never been more urgent. But our work isn’t easy. It requires resources, dedication, and independence. And that’s where you come in.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

Philip Zimbardo defends the Stanford Prison Experiment, his most famous work

What’s the scientific value of the Stanford Prison Experiment? Zimbardo responds to the new allegations against his work.

by Brian Resnick

For decades, the story of the famous Stanford Prison Experiment has gone like this: Stanford professor Philip Zimbardo assigned paid volunteers to be either inmates or guards in a simulated prison in the basement of the school‘s psychology building. Very quickly, the guards became cruel, and the prisoners more submissive and depressed. The situation grew chaotic, and the experiment, meant to last two weeks, had to be ended after five days.

The lesson drawn from the research was that situations can bring out the worst in people. That, in the absence of firm instructions of how to act, we’ll act in accordance to the roles we’re assigned. The tale, which was made into a feature film , has been a lens through which we can understand human-rights violations, like American soldier’s maltreatment of inmates at the Abu Ghraib in Iraq in the early 2000s.

This month, the scientific validity of the experiment was boldly challenged. In a thoroughly reported exposé on Medium, journalist Ben Blum found compelling evidence that the experiment wasn’t as naturalistic and un-manipulated by the experimenters as we’ve been told.

A recording from the experiment reveals that the “warden,” a research assistant, told a reluctant guard that “the guards have to know that every guard is going to be what we call a ‘tough guard.’” The warden implored the guard to act tough because “we hope will come out of the study is a very serious recommendation for [criminal justice] reform.” The implication being that if the guard didn’t play the part, the study would fail.

Additionally, one of the “prisoners” in the study told Blum that he was “acting” during a what was observed to be a mental breakdown.

These new findings don’t mean that everything that happened in the experiment was theater. The “prisoners” really did rebel at one point, and the “guards” were cruel. But the new evidence suggests that the main conclusion of the experiment — the one that has been republished in psychology textbooks for years — doesn’t necessarily hold up. Zimbardo stated over and over the behavior seen in the experiment was the result of their own minds conforming to a situation. The new evidence suggests there was a lot more going on.

I wrote a piece highlighting Blum’s exposé and putting the prison experiment in the larger context of psychology’s replication crisis. Our headline stated “we just learned it [the Stanford Prison Experiment] was a fraud.”

Fraud is a moral judgment. And Zimbardo, now a professor emeritus, wrote to Vox, unhappy with this characterization of his study. (You can Zimbardo’s full written response to the criticisms here .)

So I called Zimbardo up to ask about the evidence in Blum’s piece. I also wanted to know: As a scientist, what do you do when the narrative of your most famous work changes dramatically and spirals out of your own control?

The conversation was tense. At one point, Zimbardo threatened to hang up.

Zimbardo believes Blum (and Vox) got the story wrong. He says only one guard was prodded to act tougher. (We did not discuss Blum’s evidence that the “prisoners” in the experiment were held against their will, despite pleas to leave.)

After talking with him, the results of the prison experiment still seem unscientific and untrustworthy. It’s an interesting demonstration, but should enduring lessons in psychology be based off of it? I doubt it.

Here’s our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity.

Brian Resnick

Here’s my understanding of the criticisms that have come to light recently about the Stanford Prison Experiment.

For years, the conclusion that has been drawn from the study was that circumstances can bring out the worst in people or encourage bad behavior. And when some people are given power, and some people are stripped of it, that fosters ugly behavior.

What’s comes to light — what I got out of that Ben Blum’s report — was that it might not have all been the circumstance. That these guards that you employed were possibly coached in some ways.

There’s audio. And for me, it sounded pretty compelling that the warden in your experiment, who I understand was an experimental collaborator — was calling out a guard for not being tough enough. [The warden told the guard, “The guards have to know that every guard is going to be what we call a ‘tough guard.’” Listen to the tape here .]

So does that not invalidate the conclusion?

Philip Zimbardo

Not at all!

And why not?

Because he’s talking to one guard who was doing nothing. These are people we’ve hired who are doing it for a salary, $15 a day, to play the role of guard. And Jaffe [the warden] picks on this guy because he is doing nothing. He’s sitting on the sideline, doing nothing, watching. He’s gotta earn his keep as a guard.

The point is telling a guard to be tough does not mean telling a guard to be mean, to be cruel, to be sadistic, which many of the guards became of their own volition playing the role of what they thought was a prison guard. So I reject your assumption entirely.

Here’s the description of the experiment as written on your website: It says “the guards made up their own set of rules which they carried into effect.” In another paper , you wrote that the guards’ behavior was left up “to each subject’s prior societal learning of the meaning of prisons.”

But here’s a different possibility: Do you think it is possible that some of these guards were acting to please you, to please the study, and to do something good for science?

Even without telling the guards to explicitly do something, they might have gotten the impression that it was important for them to play these roles. And they were compelled to because of your authority.

Some of them might, but I think most of them didn’t.

For many of them, it was simply a way to make $15 a day during a two-week summer break between summer school and the start of classes in September. It was nothing more than that. It was not wanting to help science.

Some of them were increasingly mean, cruel, and sadistic way beyond any definition of tough. Some of them were guards who simply enforced the rules. And some of them were “good guards” who never did anything abusive to the prisoners. So it’s not that the situation brought a single quality in the guard. It’s a mix.

The criticism that you’re raising, that Blum raised, that others are raising, is that we told the guards to do what they ended up doing. And therefore, [the results were due to] obedience to authority, and it’s not the evolution of cruel behavior in the situation of a prison-like environment.

And I reject that.

Is it possible that some of the “prisoners” in your experiment were acting, playing along?

Zero? How can you say zero?

Okay, I can’t say.

I mean, the point was they locked themselves in their cells, they ripped off their numbers, they’re yelling and cursing at the guards. So, yeah, they could be acting. But why would they be acting. ... What would they get out of that?

Blum quoted one of the prisoners, Douglas Korpi, who had a breakdown. Korpi told Blum that he was acting. That he was in the midsts of studying for the GREs and just really wanted to get out of the experiment. Korpi told Blum, “Anybody who is a clinician would know that I was faking.”

Brian, Brian, I’m telling you every fucking thing that Ben Blum said is a lie; it’s false.

Nothing Korpi said to Ben Blum has any truth, zero. Look at Quiet Rage [a documentary about the prison experiment], look at where he says, “I was overcome in that situation. I broke down, I lost control of myself.”

Retrospectively now, he’s ashamed of having broken down. So he says he “was studying the Graduate Record Exam, I was faking it, I wanted to show I could get out and liberate my colleagues,” etc, etc.

So he is the least reliable source of any information about the study, except he documents the power of the situation to get somebody who’s psychologically normal, 36 hours before, who in an experiment, knowing it’s an experiment, has an emotional “breakdown,” and had to be released.

Let’s say: Regardless of whether guards were coached or not...

Brian, I’m gonna stop you.

Can I finish the question?

A guard, a single guard, okay? When you say guards you’re slipping back into your assumption, you’re slipping back to be like Blum. A guard was coached to be tough, and end of sentence there.

[Note: As a reminder, the tape of the experiment quoted the Jaffe, the “warden,” who played a critical role in leading the experiment, as saying, “The guards have to know that every guard is going to be what we call a ‘tough guard.’” Also, as Blum discovered in the Stanford archives, Jaffe wrote in his notes , “I was given the responsibility of trying to elicit ‘tough-guard’ behavior.” Which, again, raises suspicions that the experiment wasn’t as naturalistic as the experimenters implied.]

What I want to ask is: What is the case that this experiment should be seen as anything more than an anecdote? I don’t think anyone denies its historical value. It’s an interesting demonstration. Ideas that generated from it are worthwhile to follow up on and to study more carefully. Do you think the experiment itself has a definitive scientific value? If so, what is it?

It depends what you mean by scientific value. From the beginning, I have always said it’s a demonstration. The only thing that makes it an experiment is the random assignment to prisoners and guards, that’s the independent variable. There is no control group. There’s no comparison group. So it doesn’t fit the standards of what it means to be “an experiment.” It’s a very powerful demonstration of a psychological phenomenon, and it has had relevance.

So, yes, if you want to call it anecdote, that’s one way to demean it. If you want to say, “Is it a scientifically valid conclusion?” I say ... it doesn’t have to be scientifically valid. It means it’s a conclusion drawn from this powerful, unique demonstration.

Would you agree, as a scientist, that an early demonstration of an idea is bound to be reinterpreted in time, bound to be reevaluated?

Oh, they should. The essence of science is you don’t believe anything until it has a) been replicated, or b) been critically evaluated, as the study is being done now. I’m hoping a positive consequence of all of this is a better, fuller appreciation of what happened in the Stanford prison study.

Let me just add one thing: There are many, many classic studies that are now all under attack. ... by psychologists from a very different domain. It’s curious.

I’ve talked to a lot of researchers who are interested in replication, and reevaluating past work. They want to correct the record. I think they’re scared about what happens to the credibility of science if they don’t scrutinize the classics.

And I wonder from your point of view, as a scientist, do you need to be okay with losing control of the narrative of your work as it gets reevaluated?

Of course. The moment, the moment any of it was published, the moment any of this was put online, which I did as soon as I could, I lost. ... You lose control of it. Once it’s out there it’s not in your head anymore. Once it’s out in any public forum, then, of course, I lost control of “the narrative.”

Is it a study with flaws? I was the first to admit that many, many years ago.

A study like the prison experiment might just be too big and complicated, with too many inputs, too many variables, to really nail down or understand a single, simple conclusion from it.

The single conclusion is a broad line: Human behavior, for many people, is much more under the influence of social situational variables than we had ever thought of before.

I will stand by that conclusion for the rest of my life, no matter what anyone says.

I’m just unsure if we have the evidence to say if it’s true or not.

There are other researchers who are trying to drill down more into understanding what turns bad behavior on and off. And I’m sure you’re not a fan of him, but Alexander Haslam — [a psychologist who has tried to replicate the prison experiment study, and an academic critic of Zimbardo’s conclusions]

Oh, God! ... no, no, no.

You don’t want to talk about him.

Yeah, okay, No, I don’t want to talk about [him] at all.

Well, the gist of what he and his colleagues are arguing is this: Social identity is a really powerful motivator. And it’s perhaps more influential than situational factors. And perhaps the guards in your experiment became cruel because your warden used his authority to foster a social identity within them. [Here’s a new paper with their latest arguments. ]

I reject that. No, no. That’s their shtick, that’s what they’re pushing.

You don’t assume good faith on their part?

I’m not saying good faith. That’s what their claim to fame is the importance of social identity.

Of course people have social identity. But, there’s also something called situational identity. In a particular situation, you begin to play a role. You are the boss, you are the foreman, you are the drill sergeant, you are the fraternity hazing master. And in that role, which is not the usual you, you begin to do something which is role-bound. ... This is what anybody in this role does. And your behavior then changes.

Is there experimental evidence outside the prison experiment that supports that view?

The view that situation can make a difference?

Yeah. There are plenty of examples in history and current events, but is that something we know as a fact, as an experimental fact?

I don’t know off the top of my head. ...

I’ve always said it’s an interaction. I’m an interactionist. What I’ve said, if you read any of my textbooks, it’s always an interaction between what people bring into a situation, which means genetics and personality, and what the situation brings out in you, which is a social/psychological power of some situations over others. And I will stand by that, my whole career depends on that.

It’s not like I’m mindlessly promoting the situation is dominating everybody.

What would you fear might happen if people stop believing in the integrity of the Stanford Prison Experiment?

The fear is they will lose an important conclusion about the nature of human behavior as being, to some extent, situationally influenced.

You’re afraid they’ll lose an important conclusion even though the study is just a demonstration?

You demonstrate gravity by throwing a ball up and seeing if it comes down. I think you’re insisting on a traditional view of what is scientific, what is a scientific experiment, what is a scientifically validated conclusion. And I am saying from the beginning the Stanford Prison Experiment is a unique and powerful demonstration of how social/situational variables can influence the behavior of some people, some of the time. That’s a very modest conclusion.

All of this controversy is happening now because you gave your notes and tapes from the prison experiment to the Stanford archives. That transparency is commendable. Do you regret it?

No, I don’t regret it. The reason I did it is to make it available for researchers, for anybody, and people have gone through it.

So again, the last thing in the world I need is for people to doubt my honesty, my professional credibility. That’s an attack on me personally, and that I reject and I’m arguing it’s absolutely wrong.

Is it okay if we just move on from the Stanford Prison Experiment? Like you said, it’s a demonstration. Maybe we need to ground our understanding of acts of evil in something a little bit more scientific, to be honest.

At this point, I don’t want anyone to reject that basic conclusion that I’ve said several times in this interview. I don’t want that to be rejected. I would love for there to be better, more scientific evaluation of this conclusion, rather than a bunch of bloggers saying, “We’re gonna shoot it down.”

- Criminal Justice

Most Popular

- You’re being lied to about “ultra-processed” foods

- Take a mental break with the newest Vox crossword

- The latest chapter of It Ends With Us is an alleged Blake Lively smear campaign

- The Air Quality Index and how to use it, explained

- The Matt Gaetz ethics report, explained

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Science

Our earliest studies of Neanderthals were fundamentally flawed.

DMT, “the nuclear bomb of the psychedelic family,” explained.

It turns out cleaning your hands is more complicated than killing germs.

When you were born is actually an important risk factor for cancer.

We need new malaria drugs — so I spent a year as a guinea pig.

Xenotransplantation raises major moral questions — and not just about the pigs.

- Login or Sign up

Landmark Stanford Prison Experiment Criticized as a Sham

by Steve Horn

It’s a study widely taught in high school and college psychology textbooks as a prime example of how, as Lord Acton put it, “Power tends to corrupt; absolute power corrupts absolutely.” It’s also a study whose findings may very well have been falsely represented.

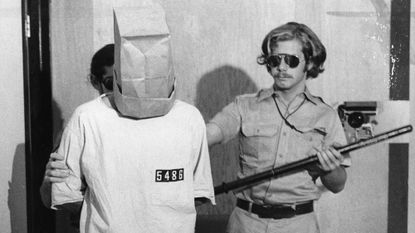

The study – the 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment carried out by Prof. Philip Zimbardo – had already been called into question over the years, yet maintained legitimacy in mainstream psychology as a landmark piece of research. Zimbardo’s study revolved around a mock prison created at Stanford University, with 24 students randomly assigned the roles of “guards” or “prisoners.” The purpose was to observe the psychological effects on the participants; expected to last two weeks, the experiment ended after just six days due to the apparent trauma that some of the students experienced.

The conclusion, both at the time the study was conducted and as it was subsequently taught for decades, was that the subjects of the mock prison experiment quickly embraced their assigned roles, with the “guards” becoming authoritarian and sadistic, and the “prisoners” accepting the abusive authority of the guards and experiencing psychological trauma. The study was funded by the U.S. Office of Naval Research.

Over the past 47 years, though, the experiment has been criticized on the grounds of both its lack of generalizability and flawed methodology. Generalizability is defined as extending research findings and conclusions from a small sample population to the larger, general population.

“Prison Study” Advertisement Flawed

The Stanford Prison Experiment has been critiqued for the fact that it involved all white men except for a single Asian-American male. It was also advertised as a “prison study” in classified ads at the time, in order to attract volunteer participants. That, critics have said, would tend to attract people already interested in the authoritarian nature of prison settings.

“Individuals high in social dominance may be drawn to volunteer for the prison study due to the explicit hierarchical structure of the prison system, and such individuals are unconcerned about the human costs of their actions,” psychologists Thomas Carnahan and Sam McFarland explained in a 2007 article published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, an academic journal.

Just as problematic, others have argued, is the issue of generalizability. That is, could this same experiment be recreated in other settings using a random sample of participants? If not, in the world of social science, big picture takeaways should not be drawn from such a small-scale study.

In this case, the students who participated did not represent a solid cross-section from the general population due to the way the experiment was advertised. Thus, critics say, general conclusions should not be drawn from the results.

Accusations of Coaching

The generalizability critiques were made before the latest round of objections to the study. The newest volley of critiques center around the implementation of the study itself. While academic research typically includes an in-depth explanation of the methodology used, Professor Zimbardo was not fully transparent about his methods, and the study was not peer-reviewed – the gold standard in academia. The full scope of those methods finally came to light almost a half-century later, in the form of audio recordings and other documentation in historical archives housed at Stanford.

The first person to track down those materials was Le Texier Thibault, a French academic and filmmaker, who wrote up his findings in a book titled Histoire d’un Mensonge (History of a Lie). His book came out in April 2018, but did not become a news story in the U.S. until June, when author Ben Blum wrote an extensive blog post about Thibault’s conclusions. In the aftermath of that post, the “sham” of Zimbardo’s study – as Blum called it in his article – made international headlines. The article, titled “ The Lifespan of a Lie ,” went beyond Thibault’s archival findings by interviewing several of the students who participated in the study, as well as Prof. Zimbardo himself.

“Anybody who is a clinician would know that I was faking,” Douglas Korpi, one of the original student volunteers, told Blum in an interview. “If you listen to the tape, it’s not subtle. I’m not that good at acting. I mean, I think I do a fairly good job, but I’m more hysterical than psychotic.”

Zimbardo was accused of telling the students how to act before and during the study. Those were not new critiques, as they had been aired in a 2005 article by a consultant to the Stanford Prison Experiment who had spent 17 years incarcerated at San Quentin. But they had a new level of gravitas due to the fact that they came via the lens of primary archival materials and interviews, not merely hearsay.

For example, in a recording, one of Zimbardo’s assistants, David Jaffe, was heard telling a “guard” to be tougher with the “prisoners” – indicating that the participants were coached. “We really want to get you active and involved because the guards have to know that every guard is going to be what we call a ‘tough guard,’” Jaffe said in the recorded conversation.

“Serious Fraud”

The timing of Prof. Zimbardo’s study was important, as it was conducted in 1971 – the same year as both the Attica and San Quentin prison riots. His research offered a simple explanation for such incidents: the prison environment created monsters of everyone involved and it was the nature of the carceral system itself that should bear the blame. Not long after his study came out, Zimbardo was invited to testify before Congress at a special hearing in San Francisco, applying his findings to the recent riots.

“In the wake of the prison uprisings at San Quentin and Attica, Zimbardo’s message was perfectly attuned to the national zeitgeist,” wrote Blum. “A critique of the criminal justice system that shunted blame away from inmates and guards alike onto a ‘situation’ defined so vaguely as to fit almost any agenda offered a seductive lens on the day’s social ills for just about everyone.”

According to a 2017 academic paper , 95 percent of criminologists have cited Zimbardo’s study without skepticism since 1971. Further, the Stanford Prison Experiment is often taught in most entry-level psychology and criminology courses with little critique, and as a seminal study in the field. It has also been made even more famous via the release of a movie, “ The Stanford Prison Experiment ,” which won two awards at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival.

Zimbardo’s colleagues in the psychology community have called the recent critiques of his research a watershed moment not only within academia, but for the impact on psychological research more generally.

“The Stanford Prison [Experiment] – as it is presented in textbooks – presents human nature as naturally conforming to oppressive systems. This is a lesson that extends well beyond prison systems and the field of criminology – but it’s wrong,” wrote Jay Van Bavel , a professor of neuroscience and psychology at New York University.

Van Bavel’s colleague at NYU, psychology professor David Amodio, further examined the real-world effects that Zimbardo’s famous study has had.

“The serious fraud seems to have occurred between Zimbardo and a complicit audience in the media, policy makers, and general public. Zimbardo couldn’t convince his scientific peers in social psychology, so he circumvented the field and went straight to the people,” Amodio stated . “This, to me, is a very different kind of fraud – it’s not about a breach in scientific practice, but in how science is communicated and consumed....”

Queensland University psychologist Alex Haslam had tried to recreate the study in 2002, but the subjects in his study who assumed the roles of “guards” did not become brutal or abusive. “We didn’t reproduce that core finding” from the Stanford Prison Experiment, he said. “The standard account [of the research] has no credibility whatsoever now.”

Zimbardo’s Response

Prof. Zimbardo, now 85 years old, posted a lengthy rebuttal to the latest round of critiques on the study’s website, www.prisonexp.org/response.

“For whatever its flaws, I continue to believe that the Stanford Prison Experiment contributes to psychology’s understanding of human behavior and its complex dynamics,” he wrote. “Multiple forces shape human behavior: they are internal and external, historical and contemporary, cultural and personal. The more we understand all of these dynamics and the complex way they interact with each other, the better we will be at promoting what is best in human nature.”

The renewed debate about Zimbardo’s scholarship, should it extend beyond the walls of academia and into the world of public policymaking, could have profound impacts on the future of policies concerning incarceration for years to come.

Sources: www.researchgate.net, www.static1.squarespace.com, www.psych.nyu.edu, www.psypost.org, www.tandfonline.com, www.vox.com, www.pitt.edu, www.searchworks.stanford.edu, www.netflix.com, www.journals.sagepub.com, www.stanforddailyarchive.com, www.editions-zones.fr, www.threadreaderapp.com, www.globalnews.ca

As a digital subscriber to Prison Legal News, you can access full text and downloads for this and other premium content.

Subscribe today

Already a subscriber? Login

More from this issue:

- $12.5 Million to Settle Class Action Suit Over Strip Searches of NYC Jail Visitors , by Anthony Accurso

- Washington State: Jail Phone Rates Increase as Video Replaces In-Person Visits , by Steve Horn, Iris Wagner

- Florida: Federal Prison Guard Sentenced for Accepting Bribe , by Monte McCoin

- Class-action Settlement in Mississippi “Debtors’ Prison” Case , by Derek Gilna

- Colorado Accused of Failing to Comply with Settlement in Mental Health Care Suit , by Derek Gilna

- California Attorney Specializes in Representing Prisoners Victimized by Fraud , by Monte McCoin

- Angola Prison Lawsuit Poses Question: What Kind of Medical Care do Prisoners Deserve? , by Amanda Aronczyk, Katie Rose Quandt

- Pro se Texas Prisoner Wins $250,550 Default Judgment in Use of Force Case , by Edward Lyon

- Humanism to be Recognized as Approved Faith in North Carolina Prisons , by Kevin Bliss

- Louisiana Jail Settles with DOJ Over HIV Discrimination , by Dale Chappell

- Rhode Island: Life-sentenced Prisoner is “Civilly Dead,” Cannot Pursue Tort Claim , by Christopher Zoukis

- Florida ICE Detention Center Restricts Detainees’ Observance of Ramadan , by Steve Horn

- Australian Woman Gives Birth in Cell After Guards Can’t Unlock the Door , by Monte McCoin

- Low Pay, High Staff Turnover Drive Texas Prison Guard Shortage , by Matthew Clarke

- Nebraska County, Jail Medical Provider Settle Suit Over Medication Denial for $10,000 , by Matthew Clarke

- Iowa Prison Guard Wins $2 Million on Retaliation, Disability Accommodation Claims , by Edward Lyon

- New York: $100,000 to Settle Suit over Rape of Trans Prisoner Held in Men’s Prison , by Christopher Zoukis

- Lawsuit Over Prisoner Assault at Tennessee Jail Results in Settlement, Dismissal , by Kevin Bliss

- Ninth Circuit Modifies Deliberate Indifference Analysis for Pretrial Detainees’ Inadequate Medical Care Claims , by Matthew Clarke

- Landmark Stanford Prison Experiment Criticized as a Sham , by Steve Horn

- U.S. Marshals Capture Fugitive Former Prison Guard After 10 Years on the Run , by Monte McCoin

- Kentucky Reluctantly Returns to Prison Privatization

- New Jersey County Pays $95,000 to Female Lawyer “Wanded” Between Legs at Jail , by Christopher Zoukis

- Federal Jury Awards $6 Million to Epileptic Colorado Prisoner, but New Trial Ordered , by Matthew Clarke

- $10 Million Class-action Lawsuit Against Virginia Jail Results in $725,000 Settlement , by R. Bailey

- HRDC Files Censorship Suit Against New Mexico Jail; Court Orders Dismissal Based on Mootness , by Steve Horn

- Florida Lawyer Arrested for Jail Porn Escapades

- Two Former Oklahoma Death Row Prisoners Obtain $3.15 Million Settlement , by Derek Gilna

- Jury Awards North Carolina Prisoner $15,000 for Staff Sexual Assault

- Formerly Incarcerated Chef Plans to Revolutionize Ramen , by Steve Horn

- Kentucky Law Requiring Abused Spouse to Pay for Abuser’s Divorce Attorney Abolished

- Fifth Circuit Upholds Convictions of Louisiana Jail Staff for Failing to Stop Abuse , by Matthew Clarke

- North Carolina Fined $190,000 for Mismanagement of Prescription Medication , by Monte McCoin

- Arizona: Lawsuit Spurs Significant Reforms for Death Row Prisoners , by Derek Gilna

- Oregon County Pays $2.85 Million for Dehydration Death of Mentally Ill Jail Prisoner , by Dale Chappell

- Black Liberation Army Members Convicted of Murdering Cops Granted Parole , by Christopher Zoukis

- Editorial: The Case Against Florida’s Amendment 4 on Felon Voting Rights , by Paul Wright

- Private Prison Company Pays to Play; Federal Election Commission Fails to Act , by Christopher Zoukis

- The Big Business of Prisoner Care Packages: Inside the Booming Market for Food in Pouches , by Taylor Elizabeth Eldridge

- Solitary Confinement Reforms Sweeping the Nation but Still Not Enough , by Christopher Zoukis

- From the Editor , by Paul Wright

- Advocacy Groups Call for End to Ban on In-person Visits at Tennessee Jail

- News in Brief

- US Parole Activists Aim to Overhaul a Failing System , by Jean Trounstine

More from Steve Horn:

- Lack of Academic Research in U.S. on Secondary DNA Transfer Affects Criminal Defendants , Oct. 14, 2019

- Opioid Epidemic Impacts Prisons and Jails , Sept. 5, 2019

- Report Finds Lack of Reporting on Deaths in Law Enforcement Custody, Even After Landmark Legislation , July 17, 2019

- New Study Finds Mass Incarceration Impacts Over Half of U.S. Families , July 2, 2019

- HRDC Files Public Records Suits, Argues GEO Group is a De Facto Public Agency , June 3, 2019

- DEA Used Decades of Warrantless Phone Data in Building Parallel Construction Cases , May 15, 2019

- Inspector General: California Prison Guards Violate Use of Force Policies Half the Time , May 2, 2019

- Vermont Prisoner Sexually Abused at Private Prison in Michigan Receives $750 , May 2, 2019

- California Prison Psychiatrists Blow Whistle on Poor Mental Healthcare, Falsified Records , April 2, 2019

- Ohio County Jail Settles PLN Censorship Suit for $45,000 , April 2, 2019

More from these topics:

- U.S. Sentencing Commission Publishes Data Report on Compassionate Release in FY 2023 , Oct. 1, 2024. COVID-19 , Statistics/Trends , Compassionate Release , Official Report .

- One of Eight Prisoners Now Released is a Woman , Sept. 15, 2024. Gender Discrimination -- Women , Statistics/Trends .

- The 153 Exonerations in 2023 Include 19 Resulting From Threats or Sentences of Death , July 15, 2024. Statistics/Trends , Wrongful Conviction .

- Decoding Recidivism: Unraveling Its Complex Metrics and Real Impact , July 1, 2024. Statistics/Trends .

- Report Finds Inaccurate Field Drug Tests Major Cause of Wrongful Convictions , June 15, 2024. Drug Testing , Statistics/Trends , Databases , Wrongful Conviction , False Arrest .

- Push Notifications Pull to the Forefront , June 15, 2024. Statistics/Trends , Police State-Surveillance , Electronic Surveillance .

- Executions Rise in 2023, Number on Death Row Falls , June 1, 2024. Criminal Prosecution , Statistics/Trends , Death Penalty , Death Row .

- Dixie Prison Growth Drives Number of Incarcerated Americans Above 2 Million Once Again , June 1, 2024. Statistics/Trends .

- U.N. Panel Finds Rampant Racism in U.S. Criminal Justice System , June 1, 2024. Racial Discrimination , Commentary/Reviews , Crime/Demographics , Criminal Prosecution , Statistics/Trends .

- New Data From BOP Reveals Technical Violations Account for Nearly a Third of First Step Act Recidivism , May 15, 2024. Crime , Statistics/Trends , First Step Act , Probation, Parole & Supervised Release , Revocation Proceedings .

- Entertainment

Everything You Know About the Stanford Prison Experiment Is Wrong

I n August 1971, at the tail end of summer break, the Stanford psychology professor Philip Zimbardo recruited two dozen male college students for what was advertised as “a psychological study of prison life.” The basement of a university building was transformed into a makeshift prison. Some of the young men were assigned to be prisoners; the others became guards. The study turned dark almost immediately, as guards drunk on power mocked, humiliated, and cruelly punished their charges. Prisoners had breakdowns. Zimbardo had to shut down the study, which was supposed to run for two weeks, after just six days. While the experiment had been egregiously unethical, it did prove that circumstances have the power to make normal people act like tyrants—or what Zimbardo has called “the power of the situation.”

So goes the legend of the Stanford Prison Experiment, cemented over more than half a century with lots of help from pop culture. Rocketed to fame when the Attica prison uprising dominated headlines just weeks after his study concluded, the media-savvy Zimbardo (who died in October) spent much of his career promoting the theory that putting good people in bad situations makes them do bad things. Abu Ghraib was, for obvious reasons, another big moment for him. When the acclaimed indie film The Stanford Prison Experiment hit theaters in 2015, starring Billy Crudup as Zimbardo and a pre- Succession Nicholas Braun as a subject, it joined a global canon of movies that reinforced his read on what happened in that Stanford hallway. The problem, as director Juliette Eisner demonstrates in her riveting Nat Geo documentary series The Stanford Prison Experiment: Unlocking the Truth , is that Zimbardo’s account of the study was far from definitive. The conclusions he drew about our moral malleability may be more pop psychology than science.

Many of the short docuseries that proliferate on streaming play like features chopped into episodes for viewers who’d rather binge on TV than commit to a whole movie. But the three-part Unlocking the Truth , which premieres Nov. 13 (and will stream the following day on Hulu and Disney+), functions as a true triptych. Through new interviews with participants and clips of the so-called “Stanford County Prison,” the first episode provides a chronology of the experiment that is largely faithful to Zimbardo’s version. The second, titled “The Unraveling,” introduces Thibault Le Texier, a French researcher who has worked to debunk the experiment, and intersperses his insights with more participant interviews that complicate or outright contradict Zimbardo’s account. Twenty minutes into the episode—at what is roughly the midpoint of the series—onscreen text informs us that the prison clips we’ve been watching aren’t footage from the study but reenactments shot on a soundstage by Eisner's team, as “only a fraction of the experiment was filmed in 1971.” The finale pairs one of Zimbardo’s last-ever interviews with scenes of the real participants visiting the soundstage, advising the actors who portray them on what really happened and talking amongst themselves about the experience and its legacy.

A long history of Stanford Prison Experiment dissent

Psychologists have been critiquing the Stanford Prison Experiment for as long as it’s been part of the discourse, though their points have mostly failed to penetrate the public consciousness. Erich Fromm picked apart Zimbardo’s methods in his 1973 book The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness , concluding that “ the difference between the mock prisoners and real prisoners is so great that it is virtually impossible to draw analogies from observation of the former.”

In 2002, the BBC aired a program called The Experiment , which documented British psychologists Alex Haslam and Steve Reicher’s restaging of the Stanford study . With an onsite ethical committee and the experimenters observing rather than participating (Zimbardo had acted as SCP’s superintendent), the prisoners wound up banding together and using their solidarity to extract better conditions. Haslam and Reicher have also noted that Zimbardo might’ve influenced guards’ behavior by making suggestions like this direct quote from a pre-experiment training session: “You can create in the prisoners feelings of boredom, a sense of fear to some degree, you can create a notion of arbitrariness that their life is totally controlled by us, by the system, you, me… They can do nothing, say nothing, that we don't permit.” (There is, of course, the possibility that the presence of TV cameras affected the outcome of Haslam and Reicher's own experiment.)

Even the ad Zimbardo placed to recruit participants could have unwittingly influenced the behavior he observed. As Maria Konnikova described in a New Yorker essay that coincided with the 2015 film, psychologists Thomas Carnahan and Sam McFarland found , in 2007, that the presence of the words “prison life” in the ad likely narrowed the field of potential participants. When they ran their own experiment to see if they would receive different types of respondents by publishing the ad both as written and with the latter phrase omitted, Konnikova writes, they found that “those who thought that they would be participating in a prison study had significantly higher levels of aggressiveness, authoritarianism, Machiavellianism, narcissism, and social dominance, and they scored lower on measures of empathy and altruism.”

How Unlocking the Truth furthers the case against the Stanford Prison Experiment

Le Texier, who published his findings in an American Psychologist article and the book Investigating the Stanford Prison Experiment: History of a Lie , identified additional problems with the study by scrutinizing Zimbardo’s archives. In the series, he explains that not only did the professor hold a “Day 0” orientation for guards in which he encouraged them to make prisoners feel powerless; he also distributed documents to them including a list of rules and suggested daily schedule. Along with making choices for the guards that they were represented as having made on their own, Zimbardo’s extensive instructions made it unclear whether the guards should’ve seen themselves as subjects of the experiment or as confederates in running it.

But Le Texier is far from Eisner’s only source who breaks with Zimbardo. Doug Korpi, a prisoner who was sent home after what has been portrayed as an emotional breakdown, says he was really just acting out of frustration after discovering how tough it would be to get dismissed from what he viewed as a bad job. A guard named John Mark recalls the warden, a grad student of Zimbardo’s, taking him aside for a “pep talk” urging Mark to be tougher on inmates. Dave Eshleman, the notorious guard nicknamed “John Wayne” (not a compliment among college students of the era), has said before that he was an actor and saw the experiment as a role. Here, he also notes that he and other subjects perceived Zimbardo’s goal of indicting the carceral system, supported that aim, and thus behaved in a way that reflected that “we would’ve done anything to prove this prison system was an evil institution.” (Now, as Eisner shows us, the theatrical Eshleman plays in a British Invasion tribute band.)

Most remarkable, to my mind, is Eisner’s interview with a man, identified in Le Texier’s research, named Kent Cotter. “I’m the guy that you never heard about, that you should be hearing about,” he says. (Indeed, googling “Kent Cotter” with “Stanford Prison Experiment” before Unlocking the Truth ’s premiere yielded zero English-language results.) “Because I am the guy that quit.” Assigned to be a guard, Cotter showed up to the training session but was alienated by Zimbardo’s agenda, as well as by his fellow guards’ gleeful plans for tormenting prisoners. “I felt more and more isolated from that group,” he recalls. So he quit before the experiment even started. “This was set up for the guards to abuse, so how could it go any other way?”

Why Zimbardo’s interpretation has persisted for so long

In his American Psychologist paper , Le Texier identifies four reasons why the Stanford Prison Experiment has remained so influential, despite conspicuous flaws. Two explanations have to do with ongoing debates around situationism —the idea that circumstances, more than personality, drive human behavior—within the field of psychology. Le Texier also concludes that:

"The SPE survived for almost 50 years because no researcher has been through its archives. This was, I must say, one of the most puzzling facts that I discovered during my investigation. The experiment had been criticized by major figures ... yet no psychologist seems to have wanted to know what exactly the archives contained. Is it a lack of curiosity? Is it an excessive respect for the tenured professor of a prestigious university? Is it due to possible access restrictions imposed by Zimbardo? Is it because archival analyses are a time-consuming and work-intensive activity? Is it due to the belief that no archives had been kept?"

Finally, Le Texier acknowledges the tireless promotional efforts of the experiment’s mastermind; “in his desire to popularize his experiment,” he writes, “Zimbardo has very often made the SPE look more spectacular than it was in reality.” That’s putting it mildly. Unlocking the Truth shows clip after clip of Zimbardo flogging his findings , decades after the experiment was conducted: MSNBC , The Daily Show , a panel with the Dalai Lama, a TED Talk , etc. He shored up his legacy as the media’s favorite social psychology expert with books like 2007’s The Lucifer Effect , a best seller and APA William James Book Award winner that highlights connections between the Stanford Prison Experiment and Abu Ghraib, and by hosting the 1990 PBS series Discovering Psychology . What’s the appeal of the message he’s pushing? From police brutality to genocide, “he has a very simple explanation to these very complex world events,” Le Texier says in the series.

It shouldn’t escape our notice, either, that Zimbardo was intimately involved with several previous onscreen representations of the experiment. He co-wrote and served as an executive producer of the 1992 documentary Quiet Rage: The Stanford Prison Experiment . And the 2015 movie everyone liked so much? It’s based on The Lucifer Effect , and Zimbardo consulted on it.

What, if anything, did the Stanford Prison Experiment really prove?

Critics of Zimbardo’s work have put forth various theories as to what his experiment actually means. When you’re aware of the influence he and his aides exerted over the guards, the Stanford Prison Experiment can start to look like an exercise in confirmation bias . The BBC study, whose participants knew their conduct would be observed by a huge TV audience, might suggest that we should demand more transparency from the carceral system and similar institutions. In Unlocking the Truth , Stephen Scott-Bottoms, Professor of Contemporary Theatre and Performance at Manchester University, speaks to the effect SPE has had on the public imagination when he calls it “the most influential piece of performance art of the 20th century.”

Particularly persuasive is an argument one of the BBC researchers makes in the series. “We began to realize that actually leadership was absolutely critical,” Reicher recalls. “Because the more you look at Zimbardo’s study, you realize that the guards didn’t become guards willy-nilly. He acted as leader to tell them what to do. But without leadership, you don’t get the types of toxic behavior we saw in Zimbardo’s SPE.” In other words: The situation to which Zimbardo attributed so much power is, in truth, only as powerful as the influence exerted by its leaders.

For me, the most crucial conclusion to draw from Unlocking the Truth and other research that has challenged the SPE is that people—some of them, at least— are capable of acting as individuals regardless of the situation. Even with Zimbardo’s encouragement, not every guard turned into a monster. Cotter didn’t even stick around long enough to don his uniform. And the ones who did abuse their power often had reasons for doing so besides the reservoir of evil Zimbardo felt sure was waiting within each impressionable human soul to be tapped. Contrary to the arguments he has made over the years (Zimbardo testified for the defense in the Abu Ghraib trial), maybe people should be held accountable for their behavior within institutional or otherwise hierarchical settings. As authoritarianism trends , it’s a takeaway worth remembering.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at [email protected]

The real story behind the Stanford Prison Experiment

'Everything you think you know is wrong' about Philip Zimbardo's infamous prison simulation

- Newsletter sign up Newsletter

The Stanford Prison Experiment of 1971 is one of the most famous – and infamous – psychological experiments conducted, still discussed in classrooms and pop culture more than half a century on. But "everything you think you know about this study is wrong", filmmaker Juliette Eisner told Ars Technica .

Eisner is the director of National Geographic's recent three-part series "The Stanford Prison Experiment: Unlocking the Truth", which features many of the study's participants speaking out for the first time. She "debunks" the experiment and investigates why it has "captured imaginations" for so long, despite being "riddled" with "lies" and "manipulation".

What was the Stanford Prison Experiment?

In August 1971, a group of students were "arrested" and hauled to "Stanford County Prison", which was, in reality, the basement of the psychology building of Stanford University, in California. The men had responded to an ad from Stanford psychology professor Philip Zimbardo seeking volunteers for "a psychological study of prison life", said The New Yorker .

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Twenty-four participants – all middle class, male college students – had been chosen for the study. A coin flip decided which of them would be prison guards and which would be prisoners. Rooms in the basement were turned into makeshift cells, with a janitor's cupboard acting as "the hole" for solitary confinement.

Although the men were willing participants, they had not been warned about the mock arrests or of the exact nature of the treatment they would face. The breaches in ethics had already begun, said Ars Technica, and they would not stop for six days, when Zimbardo called off the two-week study early.

What was Zimbardo trying to prove?

Zimbardo saw his study as a follow up to 1961's Milgram experiment, in which participants administered what they believed were powerful electric shocks to victims (played by actors) at the instruction of an authority figure. "Whereas Milgram’s research was all about the power of individual authority over an individual person, the Stanford Prison Experiment was all about the ability for a system to repeatedly create situations that strongly influence behaviour," Zimbardo said in a 2009 interview .

Based on his observations of interactions between the guards and inmates, Zimbardo concluded that holding a position of power could quickly "make normal people act like tyrants", said Time . An advocate for prison reform , the psychologist hoped to demonstrate that the prison environment encouraged this dehumanisation and brutality.

What happened during the experiment?

"Things became dark almost immediately," said Time. Guards, "drunk on power", tormented prisoners, denying then sleep, forcing some to strip naked, defecate in buckets and simulate sodomy, all while bombarding them with verbal abuse. Several prisoners left the experiment early, some reporting extreme emotional distress.

On day five, Zimbardo's then-girlfriend, Christina Maslach, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, visited the "prison". She was "so appalled" with the "lack of oversight" and "immoral" nature of the study, she convinced Zimbardo to end the experiment the next day.

Why was the experiment so controversial?

The study has long been criticised for a lack of ethical guidelines and, according to Ars Technica, is credited as the reason US universities had to "overhaul" their requirements for experiments involving human subjects.

French researcher Thibault Le Texier has been a major force behind debunking the experiment's methodology and conclusions. He argues Zimbardo's conclusions were "written out an advance" and the study was "carefully manipulated", a critique "largely confirmed" by National Geographic's series, said Ars Technica. For instance, the guards received "extensive instruction" on how to best dehumanise the prisoners, said Time.

Stanford prison's pop culture "cachet" relies on the misconception that the volunteers transformed into "submissive prisoners and tyrannical guards", said The New Yorker. However, only about a third of the guards displayed abusive behaviour and even that is far from indicative: several said their behaviour was play-acting, a conscious attempt to fulfil the role they believed they had been assigned.

The idea that the participants were putting on an act to satisfy the experiment organisers suggests "the opposite of Zimbardo's conclusions", journalist Jon Ronson wrote on X , "that evil lies within us".

Did the study have any value?

In 2002, psychologists Alex Haslam and Steve Reicher restaged the prison experiment in the BBC's "The Experiment". The set-up was closely modelled on Zimbardo's study, although the guards were not coached on how to behave towards the inmates. In the BBC study, the guards did not abuse their authority and prisoners ended up defying their captors and staging a revolt.

This very different outcome "sharpens and clarifies" the meaning of the Stanford Prison Experiment, said The New Yorker. The conclusion is not that "any random human being is capable of descending into sadism", but "that our behaviour largely conforms to our preconceived expectations". If "certain institutions and environments demand those behaviours" perhaps they "can change them", too.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Cartoons Artists take on excuses, pardons, and more

By The Week US Published 22 December 24

The Explainer Bashar al-Assad and his father, Hafez, ruled Syria for more than half a century but how did one family achieve and maintain power?

By The Week UK Published 22 December 24

The Week's daily medium sudoku puzzle

By The Week Staff Published 22 December 24

The Explainer Religious community pays few taxes, receives vast subsidies and has avoided military service, provoking ire of wider society

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published 3 July 24

The Explainer Eighty years ago, the Allies carried out the D-Day landings – a crucial turning point in the Second World War

By The Week UK Published 6 June 24

Under the radar A non-profit research agency believes it has located sites of unmarked graves of prisoners

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published 14 May 24

The Explainer It is 40 years since most of Britain's coalminers went on strike, in the most bitter and divisive industrial dispute in recent history

By The Week UK Published 24 March 24

The Explainer Two days of events are being held to remember historic beach landings 80 years on

By Richard Windsor, The Week UK Last updated 6 June 24

- Contact Future's experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Advertise With Us

The Week is part of Future plc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site . © Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

6. Grievances

The first prisoner released.

Less than 36 hours into the experiment, Prisoner #8612 began suffering from acute emotional disturbance, disorganized thinking, uncontrollable crying, and rage. In spite of all of this, we had already come to think so much like prison authorities that we thought he was trying to "con" us – to fool us into releasing him.

When our primary prison consultant interviewed Prisoner #8612, the consultant chided him for being so weak, and told him what kind of abuse he could expect from the guards and the prisoners if he were in San Quentin Prison. #8612 was then given the offer of becoming an informant in exchange for no further guard harassment. He was told to think it over.

During the next count, Prisoner #8612 told other prisoners, "You can't leave. You can't quit." That sent a chilling message and heightened their sense of really being imprisoned. #8612 then began to act "crazy," to scream, to curse, to go into a rage that seemed out of control. It took quite a while before we became convinced that he was really suffering and that we had to release him.

Parents and Friends

The next day, we held a visiting hour for parents and friends. We were worried that when the parents saw the state of our jail, they might insist on taking their sons home. To counter this, we manipulated both the situation and the visitors by making the prison environment seem pleasant and benign. We washed, shaved, and groomed the prisoners, had them clean and polish their cells, fed them a big dinner, played music on the intercom, and even had an attractive former Stanford cheerleader, Susie Phillips, greet the visitors at our registration desk.

When the dozen or so visitors came, full of good humor at what seemed to be a novel, fun experience, we systematically brought their behavior under situational control. They had to register, were made to wait half an hour, were told that only two visitors could see any one prisoner, were limited to only ten minutes of visiting time, and had to be under the surveillance of a guard during the visit. Before any parents could enter the visiting area, they also had to discuss their son's case with the Warden. Of course, parents complained about these arbitrary rules, but remarkably, they complied with them. And so they, too, became bit players in our prison drama, being good middle-class adults.

Some of the parents got upset when they saw how fatigued and distressed their son was. But their reaction was to work within the system to appeal privately to the Superintendent to make conditions better for their boy. When one mother told me she had never seen her son looking so bad, I responded by shifting the blame from the situation to her son. "What's the matter with your boy? Doesn't he sleep well?" Then I asked the father, "Don't you think your boy can handle this?"

He bristled, "Of course he can – he's a real tough kid, a leader." Turning to the mother, he said, "Come on Honey, we've wasted enough time already." And to me, "See you again at the next visiting time."

DISCUSSION Compare the reactions of these visitors to the reactions of civilians in encounters with the police or other authorities. How typical was their behavior?

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Jun 13, 2018 · The Stanford Prison Experiment was massively influential. We just learned it was a fraud. The most famous psychological studies are often wrong, fraudulent, or outdated.

Jun 28, 2018 · For decades, the story of the famous Stanford Prison Experiment has gone like this: Stanford professor Philip Zimbardo assigned paid volunteers to be either inmates or guards in a simulated prison ...

Oct 12, 2018 · Further, the Stanford Prison Experiment is often taught in most entry-level psychology and criminology courses with little critique, and as a seminal study in the field. It has also been made even more famous via the release of a movie, “The Stanford Prison Experiment,” which won two awards at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival.

Nov 13, 2024 · How Unlocking the Truth furthers the case against the Stanford Prison Experiment. Le Texier, who published his findings in an American Psychologist article and the book Investigating the Stanford ...

4 days ago · The Stanford Prison Experiment of 1971 is one of the most famous – and infamous – psychological experiments conducted, still discussed in classrooms and pop culture more than half a century on ...

Jul 23, 2020 · Almost 50 years on, the Stanford Prison Experiment of 1971 remains one of the most notorious and controversial psychology studies ever devised. It has often been treated as a cautionary tale about what can happen in prison situations if there is inadequate staff training or safeguarding, given the inherent power differentials between staff and ...

To counter this, we manipulated both the situation and the visitors by making the prison environment seem pleasant and benign. We washed, shaved, and groomed the prisoners, had them clean and polish their cells, fed them a big dinner, played music on the intercom, and even had an attractive former Stanford cheerleader, Susie Phillips, greet the ...

Aug 1, 2024 · The Stanford prison experiment became a classic study of human psychology and power dynamics. Perhaps the most stunning findings were that the people who took part in the study almost instantly internalized their roles so completely that they seem to have forgotten that they even had lives outside of the prison.

The Stanford Prison Experiment: The Stanford Prison Experiment is an infamous study that was led by psychologist Philip Zimbardo in 1971. Researchers wanted to observe prison life, but chose to do this under simulated conditions instead of observing an actual prison.

The Stanford prison experiment (SPE) was a psychological experiment performed during August 1971.It was a two-week simulation of a prison environment that examined the effects of situational variables on participants' reactions and behaviors.