- About Techniques in Learning & Teaching

Interpreting Classroom Behavior: The DAE Model

As you look at this picture, what do you see .

Take a minute to jot down your first responses.

Reviewing what you have written, what do you observe about your notes.

Do your answers reflect what you actually SEE when you view this picture or what you FEEL about the people in the picture? Perhaps you wrote words which DESCRIBE the scene, such as “female student is sitting with her legs up on a table,” or maybe the words which describe FEELINGS or INTERPRETATION of the event conveyed in the picture, such as these: “a female student is rude or misbehaving because she’s not paying attention to the lesson,” or “this is a group of childish students playing pranks on each other during a lesson.”

If you skipped description to move directly to interpretation, or if you think you were “describing” but were actually “evaluating” the situation, you are not alone. Often we bypass the “who, what, when & where” and jump immediately to an interpretation or analysis of the whys of the event based on our own attitudes, beliefs, and values. Gary Weaver describes this as the “Iceberg Analogy of Culture.” The explicit behaviors, or what we observe, are often the manifestation of what lies beneath—those underlying implicit phenomena that form the major bulk of the larger “iceberg” that lies below the water.

Do you remember the movie The Titanic ? The Titanic sunk because the crew didn’t realize how large the iceberg really was below the water. In cross-cultural encounters, a similar situation may occur; we risk an iceberg “cultural collision” if we don’t take the time to examine the whole . In other words, we risk misinterpreting others’ intentions if we neglect to go below the surface to identify the underlying attitudes, beliefs, and values.

D = describe the event.

A = analyze the event/object/photo several ways.

E = evaluate your results.

Let’s look at an example that may be easier for us to understand, whatever our geographical orientation. A Korean graduate student had recently come to the US to study at an US University. While here, her parents came to visit her. As she was driving them around during a snowstorm, she accidently drove the wrong way down a one-way street because she couldn’t see the sign. Soon a police car pulled up behind her with its lights flashing. She pulled over, and as is the custom in Korea, she politely stepped out of the car to show her respect to the policeman.

You can probably imagine what the US policeman did. As expected, he immediately pulled out his gun, thinking she was going to do something to him. Let’s stop the camera a second to reflect on this scenario. What was going on in both parties’ minds? Why did the young Korean woman step out of the car? What was her intention and underlying attitudes, beliefs, and values? Why did the US policeman pull out his gun when he saw her leave her car? What assumptions, beliefs, and values was he operating from?

The DAE model is an effective tool to help us foster self-awareness of our personal and cultural assumptions and promote the importance of frame-shifting when encountering the unfamiliar.

Major pitfalls in trying to understand cross-cultural events

There are often three:

1) jumping to steps 2 or 3 (analysis or evaluation) without first doing the step 1 (description); 2) incorrectly applying step 2 by giving a wrong interpretation or analysis; and 3) providing the wrong evaluation in terms of what the person intended from their own cultural perspective.

In the case of the Korean graduate student and the policeman, each was analyzing and evaluating the scenario based on her or his own cultural background, including value system, beliefs, and attitudes. The US policeman interpreted the Korean student’s actions as aggressive while the Korean student was just trying to politely show the respect one shows a policeman in Korea.

Describe the event. The following questions are useful for this step:

- What happened?

- What was said?

- What did you see?

In other words, a careful description of what was observed becomes the focus. For example, the policeman might say, “She is stepping slowly out of her car.” He may notice that she’s female and Asian. The Korean student might say, “The policeman is getting out of his car and showing me his gun.” He is saying, “Get back in the car now.” And there could be general agreement among observers about the description set out with these factors.

Analyze the event, which involves asking the following questions:

- Why is it happening?

- What alternative explanations might be possible?

- This might mean that……

In other words, the Korean student might think, “I didn’t see any sign that I’m not supposed to drive here, so why is he pulling me over?” She might also think, “Even though he pulled me over when I didn’t do anything wrong, I’m trying to show respect by stepping out of my car.” Her parents in the back seat might think, “My daughter is trying to show her respect. Why is the policeman yelling at her?”

The policeman’s perspective might be, “Even though snow is covering the sign, she should know it’s a one way street. Not only did she violate the traffic sign, but she’s further violating the law by stepping out of the safety of her car.” For this step, it is important to provide several analyses from various different perspectives rather than providing only one analysis which represents only one perspective.

Evaluate , as the final step, requires paying attention to your initial reaction.

- What positive or negative feelings do I have about this? (my gut reaction)

- How do I feel about this object, person, or event?

Going back to our one-way street example, the policeman may evaluate, “She’s crazy! She went the wrong way, and how dare she get out of the car! What a dangerous lady!” From her point of view, “He hates me. I didn’t do anything wrong, but I showed the most respect I possibly could and he’s trying to kill me. Guns aren’t even allowed in my country. I have never even seen a gun in my life.” Nobody has to agree at this stage because each person may have a completely different evaluation.

Now, if we reflect anew on the various perspectives of ANALYSIS, we end up with a different EVALUATION of the same incident.

The DAE model can be used effectively in cross-cultural interactions to help members of each group try to reach a better understanding of the possible intent of the other group based on going “below the surface” of the cultural iceberg metaphor. As Anais Nin said, “We don’t see things as THEY are; we see things as WE are.”

Rather than allowing our perception of people and situations to substitute for reality, the DAE approach can help us try to see our students and their classroom behavior from THEIR perspective. For instance, if we observe our students behaving in the way portrayed in the picture at the beginning of the article , we may still not agree to allow this type of behavior in our classroom, but at least we can try to understand what might be underlying the behavior. Taking the time to follow the DAE exercise before responding can also help to diffuse strong emotional feelings that may end up backfiring if we choose to respond immediately.

The DAE model was designed for cross-cultural encounters, but when reflecting upon the differences that we face in the classroom—from different genders, ethnicities, generations, socio-economic backgrounds, and so on, this model could serve to help us analyze interactions with our US born students as well. Thus, the DAE model can be used with all students—not only those from a different cultural background.

by Kyoung-Ah Nam , Assistant Professor, American University, and Colleen M. Meyers , Education Specialist, University of Minnesota. See also the graphic depiction of the DAE Model .

Nam, K. A. & Condon, J. (2010) The D.I.E. is Cast: The Continuing Evolution of Intercultural Communication’s Favorite Classroom Exercise. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34 (1), 81-87.

Weaver, G. (2000). Culture, Communication and Conflict: Readings in Intercultural Relations. Boston, MA: Pearson Publishing.

Southern Hemisphere Iceberg by Liam Q , CreativeCommon Share&ShareAlike.

The Korean word “DAE (in phonetics [dæ])” carries several meanings that reflect the values of this exercise: “counter to our instincts,” “serious,” and “a foundation.” (Si-Sa Elite Korean-English Dictionary, 1996, p. 394) 대 [dae] (對 in Chinese): “the opposite; anti; against” 대 [dae] (大 in Chinese): “great,” “prominent,” “serious” 대 [dae] (臺 in Chinese): “support; a foundation”

One meaning of 대 (DAE) is “the opposite; anti; against.” That meaning of “dae,” to go against our habits or instinct, is at the core of DAE exercise. When facing something unfamiliar or that is different from our own cultural and social values, we unconsciously tend to immediately judge and evaluate rather than reflecting on what we see or what actually happened.

In addition, 대 (DAE) carries meanings of “great,” “important,” and “serious. The process of first describe and analyze before evaluate is important in order both to understand one’s own cultural biases and to better appreciate different aspects and values of other cultures. It is a mindful perspective when encountering unfamiliar.

Share this:

Tags: discussion , learning , reflection

- Comments Leave a Comment

- Categories * TILT Posts 2011-2012

- Author UMinnTeachLearn

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Click to follow tilt..

Email Address:

Featured Posts

- Enhance Cognitive Capacity to Maximize Learning

Four Key Strategies Cognitive load refers to the amount of mental effort expended in your brain’s working memory. Learners only have so much working memory available. With attention to cognitive capacity and cognitive load, we support learners in managing the Too Much Information monster. When learning new material, what may be a simple concept for […]

- Incorporating Canvas Tools: Helping Students Keep Up

As the University of Minnesota transitions from Moodle to Canvas, CEI will be highlighting some of the ways that instructors can leverage Canvas to meet learning and teaching goals. This is the first of four planned posts for this academic year. As instructors, we want students to come to class prepared, complete assignments on time […]

Online Learning Spaces – (Re)Imagining Discussions

3 Research Resources: (Re)Imagining Discussion in Online Learning Spaces How might we evaluate, measure and grade, online discussion forums? Teachers commonly opt for participation measures such as a counting the number of times and ways people participate, or the weighting of the quality of response content, or build a rubric to guide their review as […]

Developing a Learning Culture and Learning-Centered Climate

3 Resources Cultures of Learning 1. What is a culture of learning? The short answer, posted by an Edutopia blogger, is this: a culture of learning is a collection of thinking habits, beliefs about self, and collaborative workflows that result in sustained critical learning. 2. Rethinking our default definitions of learning is a crucial first step for thinking […]

The Write Situation: Assignment Clarity and Timing

With this post, we’re continuing our (re)introduction of the Teaching with Writing project’s monthly writing tips. See the Teaching with Writing pages on the Center for Writing website for teaching resources, including sample assignments and syllabi. Establish the Situation for Your Assignment “At the heart of every assignment is the rhetorical situation — someone […]

- Enhancing Deep Learning through Creative Projects in the Science Classroom

- Primary Literature Can Puzzle Undergraduates: Using the “Jigsaw” to Build Understanding

- What’s a Scholarly Workflow – and Why Do I Want One?

- Why deal with the “hard stuff” in class?

- Improving Moodle’s Usability, Part 2

- Improving Moodle’s Usability, Part 1

- Visual Thinking Strategies

- Going Large: Notes on Increasing Class Scale in an eLearning Context

- Teacher-Student BFFs? Using Multiple Tech Tools to Improve Interpersonal Academic Relationships

- That Awkward Moment when…Managing Student Embarrassment in the Academic Environment

- Feedback for Learners in the Midst of Learning – Incorporate Social Media, Stir Up Thinking

- Liberal Learning: The Richness of a Multi-Lens Perspective

- At the end of our run as a blog…

- Learning Students’ Names

- Moving from Surface to Strategic Learning

- Thesis Writing – (Not Necessarily) A Long, Solitary Journey

- What I Learned from Springsteen

- What Makes for Great Teaching? Listening to – and Learning from – My Students

- More than “get into groups of four” – Understanding “cognitive whys” & “social hows” of group work

- Creating Connections that Ease International Students’ Transitions

- Small Changes with Big Impact

- Naming Ourselves as Technology Adopters: A Nuanced Model

- “If I can get the Power Point online…”: Technologies as a mirror on higher education, Part 1

- “Learning More than We Are Taught”: Technologies as a mirror on higher education, Part 2

- Planning for Course Endings, the 2016 Update

- Is this line in your Syllabus: “Class Participation = 10%”?

- Personal Learning Meets Professional Networking

- Aiding Learners in Studying Properly

- Why do we fixate on particular data?

- Grace in our teaching: Recognizing strength

- Digital Accessibility: Small Steps for the Long Haul

- Graduate and Professional Student Involvement in the MOOC Experience

- What’s that blurry thing up there on the screen? Or, Ways and Whys to Clean Up Bad Images

- Successful Team Projects: Ideas to Begin Using Today

- Making the Switch to Affordable Course Content

- Making Sure Your Educational Multimedia Pays Off

- “History Can Be So ________ (adjective)!”

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Study and research support

- Academic skills

Critical thinking

A model for critical thinking.

Critical thinking is an important life skill, and an essential part of university studies. Central to critical thinking is asking meaningful questions.

This three-stage model, adapted from LearnHigher , will help you generate questions to understand, analyse, and evaluate something, such as an information source.

Description

Starting with the description stage, you ask questions such as: What? Where? Why? and Who? These help you establish the background and context.

For example, if you are reading a journal article, you might ask questions such as:

- Who wrote this?

- What is it about?

- When was it written?

- What is the aim of the article?

If you are thinking through a problem, you might ask:

- What is this problem about?

- Who does it involve or affect?

- When and where is this happening?

These types of questions lead to descriptive answers. Although the ability to describe something is important, to really develop your understanding and critically engage, we need to move beyond these types of questions. This moves you into the analysis stage.

Here you will ask questions such as: How? Why? and What if? These help you to examine methods and processes, reasons and causes, and the alternative options. For example, if you are reading a journal article, you might ask:

- How was the research conducted?

- Why are these theories discussed?

- What are the alternative methods and theories?

- What are the contributing factors to the problem?

- How might one factor impact another?

- What if one factor is removed or altered?

Asking these questions helps you to break something into parts and consider the relationship between each part, and each part to the whole. This process will help you develop more analytical answers and deeper thinking.

Finally, you come to the evaluation stage, where you will ask 'so what?' and 'what next?' questions to make judgments and consider the relevance; implications; significance and value of something.

You may ask questions such as:

- What do I think about this?

- How is this relevant to my assignment?

- How does this compare to other research I have read?

Making such judgments will lead you to reasonable conclusions, solutions, or recommendations.

The way we think is complex. This model is not intended to be used in a strictly linear way, or as a prescriptive set of instructions. You may move back and forth between different segments. For example, you may ask, 'what is this about?', and then move straight to, 'is this relevant to me?'

The model is intended to encourage a critically questioning approach, and can be applied to many learning scenarios at university, such as: interpreting assignment briefs; developing arguments; evaluating sources; analysing data or formulating your own questions to research an answer.

Watch the ‘Thinking Critically at University’ video for an in-depth description of a critical thinking model. View video using Microsoft Stream (link opens in a new window, available for University members only). The rest of our Critical thinking pages will show you how to use this model in practice.

This model has been adapted from LearnHigher under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 3.0.

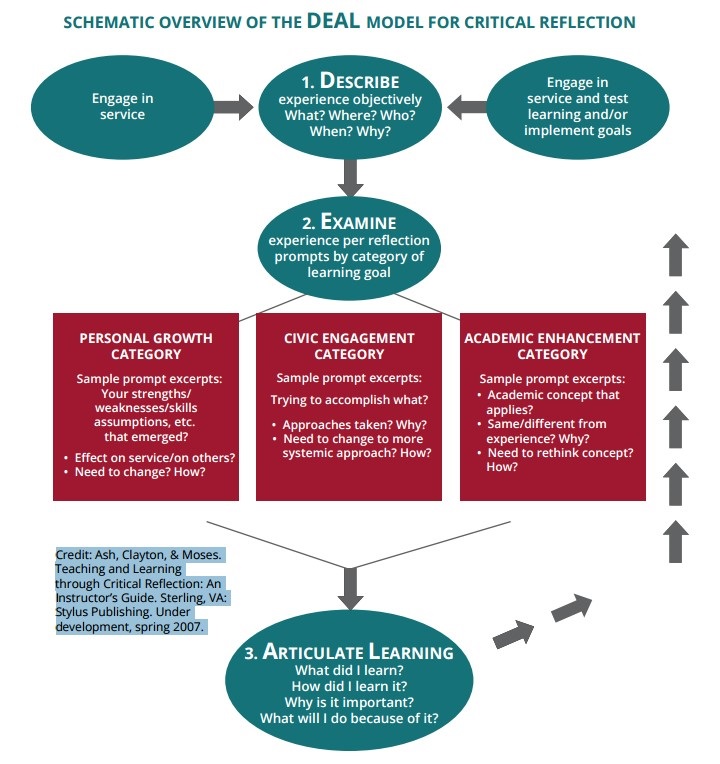

DEAL: Describe, Examine, and Articulate Learning

Ash & Clayton (2009) define Critical Reflection as “evidence based examination of the sources of and gaps in knowledge and practice with the intent to improve on both (p. 28).” With this goal in mind, they develop a structure of “best practices” for creating critical reflection assignments and the associated assessments. Facilitators of experiential learning should follow 3 steps for optimal results.

1. Determine the desired learning goals and associated learning objectives, moving from description and explanation to evaluation and critique.

2. Create reflection assignments which relate directly to these learning objectives and require higher-order critical thinking skills.

3. Integrate summative and formative assessments into the reflection assignments.

The authors represent their approach in the DEAL model: Describe, Examine, and Articulate Learning. (Diagram 2 below) Using this approach, students take responsibility for their own learning. The first step, Describe, can happen before, during, and after the EL activity. To avoid shallow lists or mundane diary entries, the reflection prompts must encourage mindful and attentive descriptions of the activity. The Examine stage of critical reflection builds upon this foundation. Reflection questions which ask the student to examine their experience allows them to make meaning out of their EL activity by identifying the links between the learning objectives and their personal experience. The final step, Articulate Learning, enables students to capture their learning so that they can act on it. This can only happen if students can clearly articulate their learning process. Answering questions such as: What did I learn?, How did I learn it? Why does it matter? and What will I do now? will transform the student’s experience into substantive, applicable learning.

For Ash & Clayton, assessment must be developed in tandem with critical reflection activities. Assessment, like the reflection questions themselves, must link explicitly with the learning goals as objectives of the EL activity. As such, assessment needs to incorporate both the Describe and the Examine aspects of the Deal model. Summative assessments would evaluate the student’s accomplishment of the learning objectives while formative assessments would provide the feedback necessary for students to act on their learning. The authors describe the creation of critical reflection and assessment as modeling the EL learning process, with the opportunity for teachers to continuously learn from their students’ responses to improve the experience, the efficacy of the reflection assignments, and student learning.

Ash, S. L., & Clayton, P. H. (2009). Generating, deepening, and documenting learning: The power of critical reflection for applied learning. Journal of Applied Learning in Higher Education , 1(1), 25-48.

Kleinhesselink K, Schooley S, Cashman S, Richmond A, Ikeda E, McGinley P, Eds. (2015). Engaged faculty institute curriculum . Seattle, WA: Community-Campus Partnerships for Health.

© 2024 University of Puget Sound

IMAGES

COMMENTS

A DAE reflection model was created as a visual guide for students, as shown in Figure 1, to encourage students to describe the situation, leading to an analysis of the situation, and then arriving ...

Mar 12, 2012 · The DAE model was designed for cross-cultural encounters, but when reflecting upon the differences that we face in the classroom—from different genders, ethnicities, generations, socio-economic backgrounds, and so on, this model could serve to help us analyze interactions with our US born students as well.

After completing the Critical thinking elective, students will be able to apply critical thinking processes to analyse the strength and validity of information and claims. Those skills are valuable for learning in Stage 6. Critical and creative thinking is a general capability in most Stage 6 courses.

Critical thinking is an important life skill, and an essential part of university studies. Central to critical thinking is asking meaningful questions. This three-stage model, adapted from LearnHigher, will help you generate questions to understand, analyse, and evaluate something, such as an information source. Description

Component: Critical Thinking ILO: To use questions to describe, analyse, evaluate & reflect on a text. ACTIVITY There are many ways to use this model. One example is to ask students to read a text relevant to the session and ask questions of it. List all the questions they have on the board, introduce the model and order them into the four ...

2. Create reflection assignments which relate directly to these learning objectives and require higher-order critical thinking skills. 3. Integrate summative and formative assessments into the reflection assignments. The authors represent their approach in the DEAL model: Describe, Examine, and Articulate Learning.